When the news broke Friday, February 7, that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) had announced it was slashing funding for biomedical research, at least two questions emerged. First: What just happened? Second: What does it mean?

The decision, which NIH said would take immediate effect, proposed a 15% cap for “indirect costs” for funded research at institutions across the country. These costs, also called Facilities and Administrative (F&A) or overhead costs, are added to NIH grant-funded projects to cover related research expenses, such as laboratory space, equipment like microscopes or test tubes, staffing, and the like.

The support bolsters the capacity of institutions like the Colorado School of Public Health (ColoradoSPH) and the University of Colorado Anschutz Campus to run complex, lifesaving research projects and clinical trials in the areas of cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and others.

In announcing the 15% cap, the NIH claimed the move would save $4 billion. How? The organization stated that “the average indirect cost rate reported by NIH has averaged between 27% and 28% over time,” and went on to say that “many organizations” charge indirect rates of “over 50% and in some cases over 60%.”

Immediate response and resistance

The abrupt NIH decision, made without input from the research institutions it would affect, caused an immediate uproar nationwide and in Colorado. Twenty-two state attorneys general, including Phil Weiser of Colorado, sued to stop the move, which is now temporarily blocked. The complaint called the NIH action “unlawful,” and stated that it would “devastate critical public health research.”

The complaint also pointed out that indirect cost rates are negotiated “based on each institution’s unique needs and cost structure.” It further stated that the rates can only be changed under specific circumstances, such as a requirement by “federal statute or regulation” or through a decision-making process that justifies the reasons for the change.

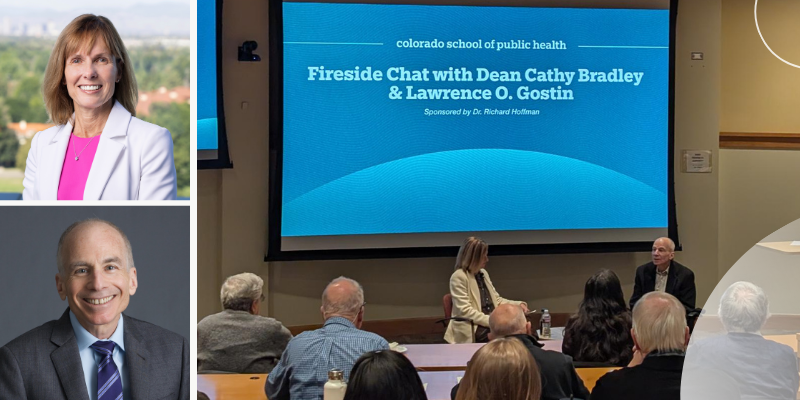

“The indirect cost rate for NIH grants cannot be changed by executive order,” said ColoradoSPH Dean Dr. Cathy Bradley. She added that the rates are negotiated based on a complex formula for each institution and cannot be interfered with without congressional approval. For University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus researchers, it is 56%.

Until this matter is resolved, Bradley said, ColoradoSPH is proceeding with its research under the terms of its existing negotiated agreements.

The school has summarized that position with “Research Funding Updates” posted on its website. Bradley reaffirmed ColoradoSPH’s central role in providing critical public health research, education, and implementation needs for the people of Colorado.

“We have a number of federal grants and we are meeting our obligations and the work that we promised that we would do,” she said.

Significant resources at stake

The Anschutz Medical Campus received nearly $350 million in NIH grant funding in fiscal year 2024. ColoradoSPH receives on average nearly $55 million, according to Bolormaa Begzsuren, associate director of Research & Grants Administration for the Office of the Dean. Slashing the current indirect cost rate to the proposed cap of 15% would create a “catastrophic loss” for ColoradoSPH, Bradley said. “We don’t have a way of making it up.” Initial ColoradoSPH estimates suggest the gap would total nearly $9 million each year.

In its statement announcing the cap, NIH officials minimized the importance of indirect costs for research, declaring that “as many funds as possible go towards direct scientific research costs rather than administrative overhead.”

Bradley – herself a past and current recipient of NIH funding – responded that “administrative overhead” is a general term that fails to illuminate what indirect costs entail in a research project. For example, an analysis of a Medicare claim files requires overhead to pay for computing resources, she said. “I can’t get that data unless I have a place to store it safely so data confidentiality cannot be breached,” she said. “That requires a massive computer with storage power and a backup system” as well as staff to maintain the system, she added. “Those things go into the overhead rate without which we no can longer afford these resources.”

Wet labs, which house experimental work, will also suffer with a massive indirect cost rate reduction, Bradley said. “To have a wet lab is extremely expensive,” she said, citing costs for insurance, equipment maintenance, and construction, such as thicker walls for work that involves radiation.

Bradley added that this funding reduction will limit the school’s ability to support research participant safety, students, and other needs.

A need for better communication about research

If there is a benefit to be gained from the recent dispute, it’s that it will compel academic institutions to do a better job of explaining to a sometimes-skeptical public the societal value of research, Bradley said.

“That is one of our greatest failings,” she said. “We have taken for granted what we know and what we provide without communicating it clearly.”

Decision makers and the public alike may not consider the economic power generated by employees across the CU system, which, when combined, is the largest employer in Colorado. The long term impact on Colorado’s economy, job market, businesses, and others will most certainly be felt if these NIH grants are cut so dramatically.

“We have not done a good job of training scientists to communicate scientific information to people with different backgrounds,” Bradley said. “This is a wakeup call for all of us in the scientific community, and ColoradoSPH is committed to doing a better job of training people from the time they are in school to understand the value and importance of public health so it is relevant to them from a very young age.”