Dr. Dana Dabelea minces no words when she discusses diabetes, a disease she has studied her entire professional life.

“It is prevalent and a plague on our society,” said Dabelea, PhD, director of the Lifecourse Epidemiology of Adiposity & Diabetes (LEAD) Center and associate dean of research at the ColoradoSPH.

Cold statistics bear her out:

- The CDC estimated that in 2021, 38.4 million people in the United States had diabetes.

- Type 2 diabetes, which interferes with the body’s ability to use insulin, is the most common, and fastest-growing, form.

- Overall, diabetes caused 339,000 deaths and cost society $413 billion in 2022, according to the American Diabetes Association.

That staggering cost is not surprising because diabetes often spawns a long list of complications, including damage to small blood vessels, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. The long-running Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study (DPPOS) has fought back by probing interventions that address those problems in people with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.

Now Dabelea and LEAD Center colleague Dr. Allison Shapiro, PhD, MPH, are among the DPPOS researchers taking on another study avenue: possible links between diabetes and cognitive decline and dementia. “Diabetes really affects all organs and systems in the body,” Dabelea explained. “Cognitive decline, including full-blown dementia, is part of the myriad of complications related to the disease.”

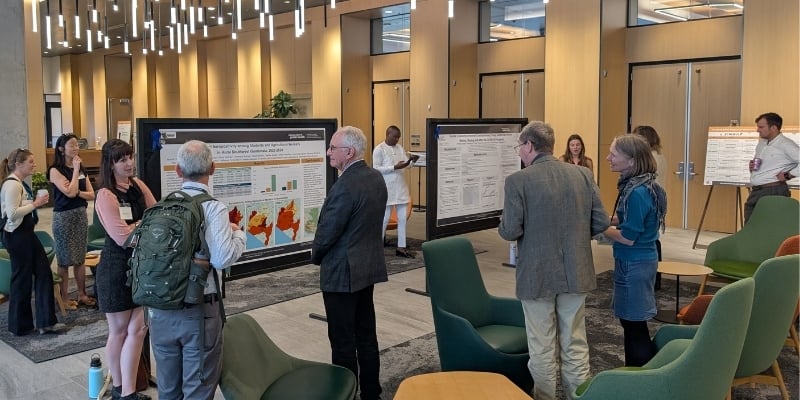

Shapiro’s and Dabelea’s work zeroes in on young people who develop type 2 diabetes. The question: are these youths at risk for developing cognitive problems later in life? A recent paper they co-authored examined a small number of people in this group, using blood samples and brain images from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study, which launched nearly 25 years ago with five centers. One of them is at ColoradoSPH on the Anschutz Medical Campus, where Dabelea is principal investigator. Its aim: explore the causes, effects, and complications of diabetes in children and adolescents.

The paper concluded that the small group in the study had biomarkers – biological warning signs – linked to cognitive decline, and the biomarkers increased as they aged. The risk factors included proteins linked to brain inflammation and degeneration, as well as beta-amyloid and tau, the damaging plaque and tangles in the brain that are culprits in Alzheimer’s disease.

Young people with type 2 diabetes live with their disease an average of 30 years longer than people who develop it as adults, Shapiro notes.

That is cause for concern, she said. “We already know that people with youth-onset type 2 diabetes perform lower on cognitive tests,” she added.

“The early appearance of these biomarkers may suggest that they are on a more accelerated trajectory of cognitive impairment.” At the same time, targeting these risk factors in childhood and adolescence could offer hope, and a reason to take action sooner, Dabelea noted. “By starting to look at [cognitive impairment] earlier in life, we open more avenues for prevention because young people don’t have dementia yet,” she said. “Diabetes is something that affects both the body and the brain,” Shapiro concluded. “What we want to do is to promote people to live the healthiest lives in their bodies so they can live the healthiest lives in their brains.”

“What we want to do is to promote people to live the healthiest lives in their bodies so they can live the healthiest lives in their brains,” said Allison Shapiro.