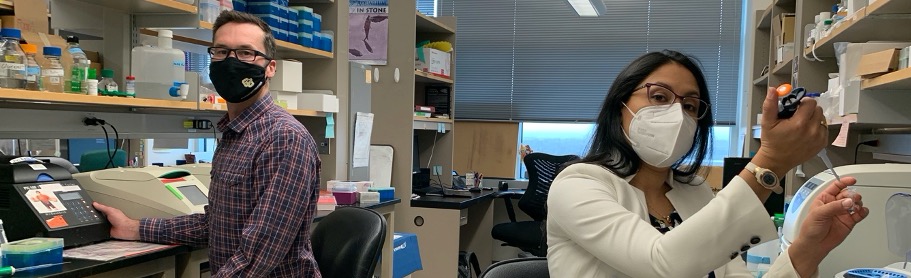

Patience. It's something most researchers need when it comes to discoveries. For Jamie Nichols, CU Dental craniofacial biology assistant professor, and his team, it took eight years to understand how genes impact a crucial component in our facial structures.

He, along with his colleague and CU Dental postdoctoral researcher, Jennyfer Mitchell, were able to identify the function of a specific gene, called alx3, that shapes the area between the eyes and above the lip. The hope is that this information can give us insight into how we can look at craniofacial abnormalities in humans, like cleft palates.

"The function that we discovered in zebrafish may be conserved in humans, which opens a world of possibilities to understand the cellular and molecular basis of the deformities we see in human patients," said Mitchell.

As Mitchell mentioned, the research team used zebrafish to make this discovery. Zebrafish are externally fertilized, so skeletal development occurs outside of the mother, making it easier for researchers to watch cartilage and bone-forming cells move around and do their job.

The team examined the genes that are active in the cells behind the fish's nostrils (nares). Then, they manipulated the gene sequences, which ultimately created changes in the fish's craniofacial skeletal structures.

"It was interesting that changing this gene changed the shape of the craniofacial skeleton without any apparent harm to the fish. They can swim and feed and breathe even though their facial skeleton has differently shaped cartilages and bones," said Nichols. "We think that genetic changes like this might provide important fuel for natural selection to produce new facial shapes and structures during evolution."

The Company of Biologists Journal Development published Nichols’ and Mitchell's research. Mitchell, the lead author of the research publication, says this is her most significant discovery.

"I have been highly motivated since the first day I joined the Nichols lab," said Mitchell. "Narrowing down to the day when I discovered the deformities in this fish, I was excited to have found a model system and area of research that makes me happy. I couldn't wait to keep deepening my analysis and find new ways to study this special group of cells responsible for building the craniofacial skeleton."

Mitchell's research, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), under a grant that focuses on the biomedical workforce. Mitchell, originally from Bogotá, Colombia—has her PhD in Cell and Molecular Biology and started working with the CU School of Dental Medicine in 2018, just a few years after the Nichols Lab was developed in 2016.

Similarly, Nichols' interest in zebrafish genetics and craniofacial development started when he was training to be a postdoctoral fellow.

"I'm very grateful for the support I've received from the School of Dental Medicine since coming to Colorado in 2016," he shared. Both Nichols and Mitchell feel similarly grateful for the funding and commitments from organizations. Nichols said, "I am also extremely thankful for the financial support I've received from the NIH and the NIDCR, including a new five-year award which will fund more studies like this one." For Mitchell, a grant like this one—referred to as an F32, secures this present study and is a step forward towards becoming a faculty member.

Nichols' newest grant will provide him and his team with $2M in funding.

He said, "There is a whole family of alx genes present in fish, and us too. Now we're finding new interesting craniofacial shapes in this same part of the skeleton when multiple alx genes are removed at the same time."

"We are also starting to look at genetic interactions with other genes outside of the alx family as possible candidates that are part of a genetic network responsible for shaping key elements of the face,” shared Mitchell.

Nichols and Mitchell know all too well—that their latest research initiative will likely take time and patience, but their excitement for discovery is ongoing.