Cancer researchers know that the Epstein-Barr virus causes certain types of stomach cancer, but what is less understood is if the unique molecular makeup of EBV-related stomach cancers makes them more responsive to certain cancer medicines.

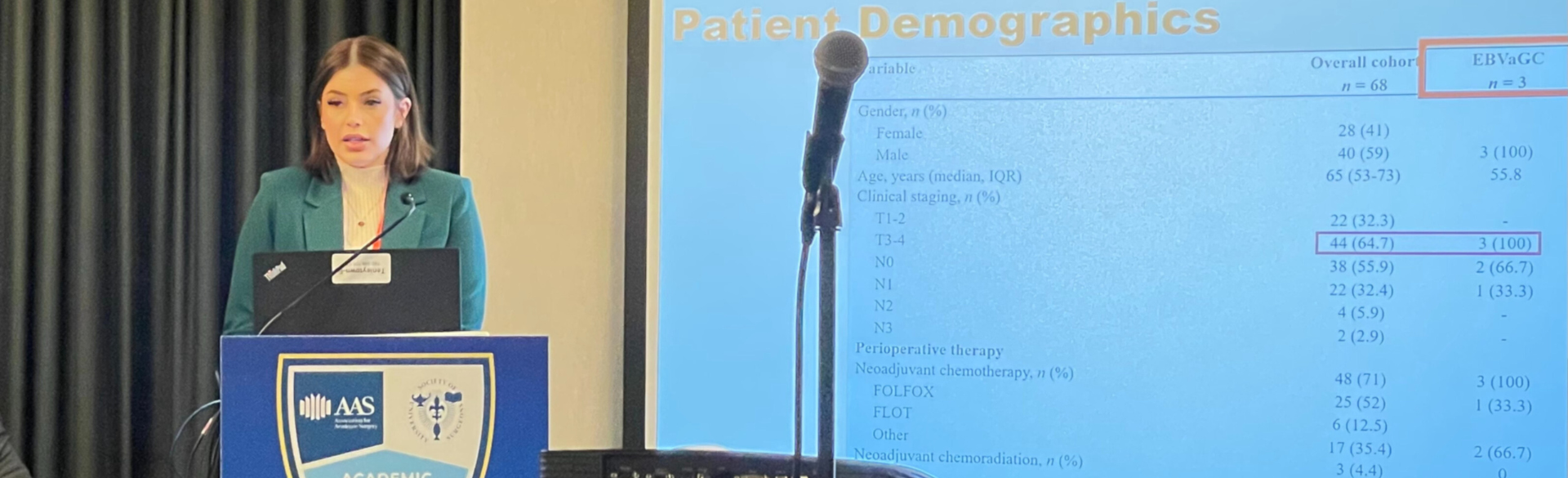

Danielle Gilbert, a fourth-year student at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, is part of a research team in the CU Department of Surgery that is investigating the issue further. Gilbert was one of the authors of a CU surgery study that analyzed tissue samples from patients with gastric cancer to look for the presence of EBV and to see how those samples differed from non-EBV cancers. The paper — whose other authors included CU surgical resident Elliott Yee, MD, and Department of Surgery faculty member Martin McCarter, MD — was published online in February in the Journal of Surgical Research.

Danielle Gilbert

Danielle Gilbert

“We focused on trying to define how Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric cancer is a different molecular entity from non-EBV gastric cancer, as well the changes we were seeing,” says Gilbert, who will soon begin her residency in the CU Department of Surgery. “Those changes included a greater number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the stroma of the tumor tissue, which in other cancers has been linked to a really good response to immunotherapy.”

The researchers also found that the EBV-associated cancers had higher levels of the protein PD-L1, a frequent target of the immunotherapy drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors

“We also found evidence of an immunosuppressive component in the EBV cells,” Gilbert says. “There were elevated levels of regulator T cells in the stroma, which has been shown in other cancers to have an immunosuppressive effect. We also found more memory T cells, which is a gold standard for cancer immunity. We don’t have evidence that EBV cancers will respond better to immunotherapy or will respond better to chemo, but we know in other cancers like melanoma and small-cell lung cancer, patients with higher levels of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and memory T cells responded better to immunotherapy.”

Award-winning research

Gilbert, a former clinical research coordinator at the CU Cancer Center, presented the paper at the 19th annual Academic Surgical Congress meeting in February in Washington, D.C., where it won the Best Manuscript Award.

“I have been doing oncology research for a long time, but this was another step up for me,” she says. “This was taking a more complex and nuanced look at cells and their functions within certain areas of a tumor. It was a great opportunity to bring clinical outcomes research together with lab research.”

Opportunities for screening

Gilbert notes that gastric cancers typically are not tested up front for the presence of EBV, though the research conducted by her and the CU surgery team could be a first step in changing that.

“In our study, we were able to identify EBV in the specimens by sending out them out to a lab,” she says. “In some cases, the EBV testing is done on the patient’s tumor sample after removal, after biopsy, or after some sort of invasive procedure to obtain tumor tissue. If it was as easy as drawing one vial of blood and seeing if that person has an EBV-associated malignancy, maybe that would look a little different.”

Eventually, she says, people with gastric cancers may be screened for EBV right away and put onto immunotherapy as a first-line treatment.

“We need more evidence to say that they might respond better to immunotherapy, but immunotherapy tends to be better tolerated and less intimidating to patients,” she says. “There’s a lot of literature to suggest that it’s best to do a partial or total gastrectomy — in some cases with neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation — but the question moving forward is, if we do identify these changes, will that lead to better responses with immunotherapy?”

Next steps

In Gilbert’s view, the next steps toward making that happen could include looking at statewide data to find the larger frequency of EBV-associated gastric cancer, what treatments those patients were started on and why, and what their outcomes were.

“It would also be important to look at samples in which we're able to get tissue and see if they are exhibiting the same changes within the lymphocytes, and where the lymphocytes are located and how they're working,” she says. “For those patients who did well on immunotherapy, were they tested for EBV? Are we able to look at these spatial distributions and correlate it closely with EBV? After that, we would want to find out how well immunotherapy is indicated, tolerated, and responded to by this population.”

.png)