From an early age, Cheri Adams, program director of regulatory strategy at the Gates Institute, knew she would pursue a career in medicine. But it was her experience as an organ donor that led her to a career in clinical research.

As an undergraduate at the University of Arizona, where she double-majored in nursing and microbiology, she worked as an assistant for Gary Gruver, PhD, a clinical psychologist who counseled students and faculty.

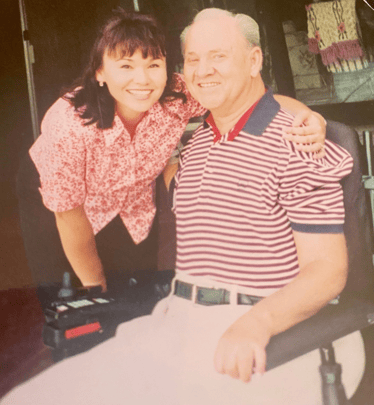

Gruver, a quadriplegic since his service in the military, needed help with a variety of tasks, including driving to campus; Adams became his “girl Friday.” Gruver was a prominent advocate for research of spinal cord injuries and was intrigued by the potential of regenerative therapies to heal these injuries. He served as a scientific reviewer for grants at the Paralyzed Veterans of America, Spinal Cord Research Foundation. It was through this work that Adams first learned about clinical trials, lessons that she draws on still.

She came to appreciate that clinical trials are at the heart of all medical advances. Such research offers hope for many people stricken with disease and disability, and the chance to find better treatments and cures.

‘I would do it again’

Over the years, Adams’ bond with Gruver grew; she considered him more than just a mentor, almost a second father, having lost her own father when she was a teen. They stayed in touch, even after she left her position to go into bench research at a Veterans Administration hospital and nursing school.

She became concerned when Gruver’s health began declining. By 2001, he had gone into renal failure, a complication from having a catheter for over 30 years. It took a toll on his mental clarity, and he had to reduce his clinical load.

“I saw him become a very different person,” says Adams. “He was tired all the time, which was hard to watch. He’d typically been the one to help others through a crisis.”

"It was an easy decision to make," Cheri Adams says of becoming a kidney donor in 2001. The recipient, Gary Gruver, PhD, was a longtime mentor and friend who ignited Adams' interest in research. Gruver passed away in 2009. |

One day, she said to him: “G, you can have one of my kidneys.”

The next week he followed up with her: “Cheri, did you really mean it?”

“Absolutely,” she responded.

Even as she weighed the decision, she viewed the procedure through a research lens, evaluating the “risk-to-benefit ratio.”

“From that perspective, it was an easy decision to make,” she says. “The risk to me was minimal; the benefit to him would be enormous.”

They underwent several blood tests to make sure they had compatible blood types as well as human leukocyte antigen tissue typing.

“I was a 4 out of 6 antigen match with Dr. Gruver,” she recalls. “With modern-day immunosuppression, kidney transplants are very successful between two people with no matching antigens.”

The benefit was almost immediate for Gruver. Adams said his mental clarity and energy levels both improved.

“It was the most rewarding experience in my life, and I would do it again,” she said. They remained steadfast friends until his death in 2009; her gift of life was mentioned in his obituary.

Good leaders attract talented teams

Adams sometimes jokes that she’s a “roadie” for scientists, following their career paths and accomplishments in the same way that a fan might follow a sports team or a band.

During her tenure at Children’s Hospital Colorado – where she worked as an oncology research nurse, then regulatory affairs lead -- she met Terry Fry, MD, who had joined University of Colorado Anschutz School of Medicine in 2018. Fry had been among the first scientists to investigate using genetically modified T-cells to target a surface protein found on leukemia cells during his time at the National Cancer Institute.

“With the pivotal introduction of (chimeric antigen receptor) CAR T immunotherapy, I knew I wanted to join his team,” says Adams.

When an opportunity arose to join the newly formed Cell Therapy Operations Program (CTOP) as a pharmacovigilance specialist at CU Anschutz, Adams didn’t think twice.

Fry led the team, which supported investigator-initiated clinical trials testing therapeutic agents produced at the Gates Biomanufacturing Facility.

Despite the demands of the job, she managed to earn her master’s degree in regulatory affairs from the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, which she attended remotely, going in-person briefly for an internship with the FDA.

.png?width=497&height=373&name=CELLS%20team%20(1).png)

In 2020, Cheri Adams became a pharmacovigilance specialist overseeing clinical trials, and is now an integral part of the Clinical Investigation and Regulatory Sciences (CELLS) team at Gates Institute. Left photo: With Terry Fry, MD, executive director of Gates Institute. Right photo: With other members of the CELLS team, from left, Gina Vanderveen, Drew Roth, and Chanel Mansfield. |

“Cheri’s background as an oncology nurse, married with her passion for regulations, gave us a critical foundation as we were building this program at CU Anschutz,” says Chanel Mansfield, associate director of clinical research at Gates Institute. “It has been a privilege to see Cheri achieve her goal of attaining a master’s degree in regulatory affairs and apply that education directly to her daily work, particularly as she moved into a new role focused on developing regulatory strategy earlier in the product lifecycle. Cheri is a key contributor to the development of Gates Institute products and continues to elevate our program with everything she brings to the table.”

Adams’ role transitioned to the Clinical Investigation and Regulatory Sciences (CELLS) team at the Gates Institute in January 2023. She has been inspired by Fry’s leadership as the executive director of the new organization.

“Good leaders not only need exceptional talent, but they also tend to have the ability to attract followers,” Adams explained. “Dr. Terry Fry is one of those natural leaders.”

“We believe in his mission,” said Adams. “He’s a talented and scientific leader in his own right. He has integrity and an unwavering dedication to cell and gene research. He honors all the patients he’s ever treated.”

Advocating for patients with few options

Gates Institute serves as an intermediary on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus, working with investigators to manage the science and the operations of the clinical trials. The institute’s work focuses on managing innovative early-phase first-in-human clinical trials with the goal of developing therapeutics for patients.

In early-stage drug development, teams must consider the science, without compromising safety or compliance, while working at a pace to help patients with urgent medical needs, Adams says.

In her role, Adams helps shepherd the therapeutics through the regulatory process, addressing federal and institutional mandates and reporting on the benefit-to-risk profile for a potential new therapeutic.

“These are bespoke therapies; it’s not a pill that you can make 10,000 of in a day,” Adams said. “It’s an ‘n of 1’ for patients, involving a complex regulatory pathway.”

And regulations can change, which requires agility from Adams and the CELLS team.

“It’s hard, but meaningful work,” says Adams. “But I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

-2.png)

%20for%20children%20and%20young%20adults%20with%20relapsed%20or%20refractory%20solid%20tumors.%E2%80%9D%20(1)-1.png)