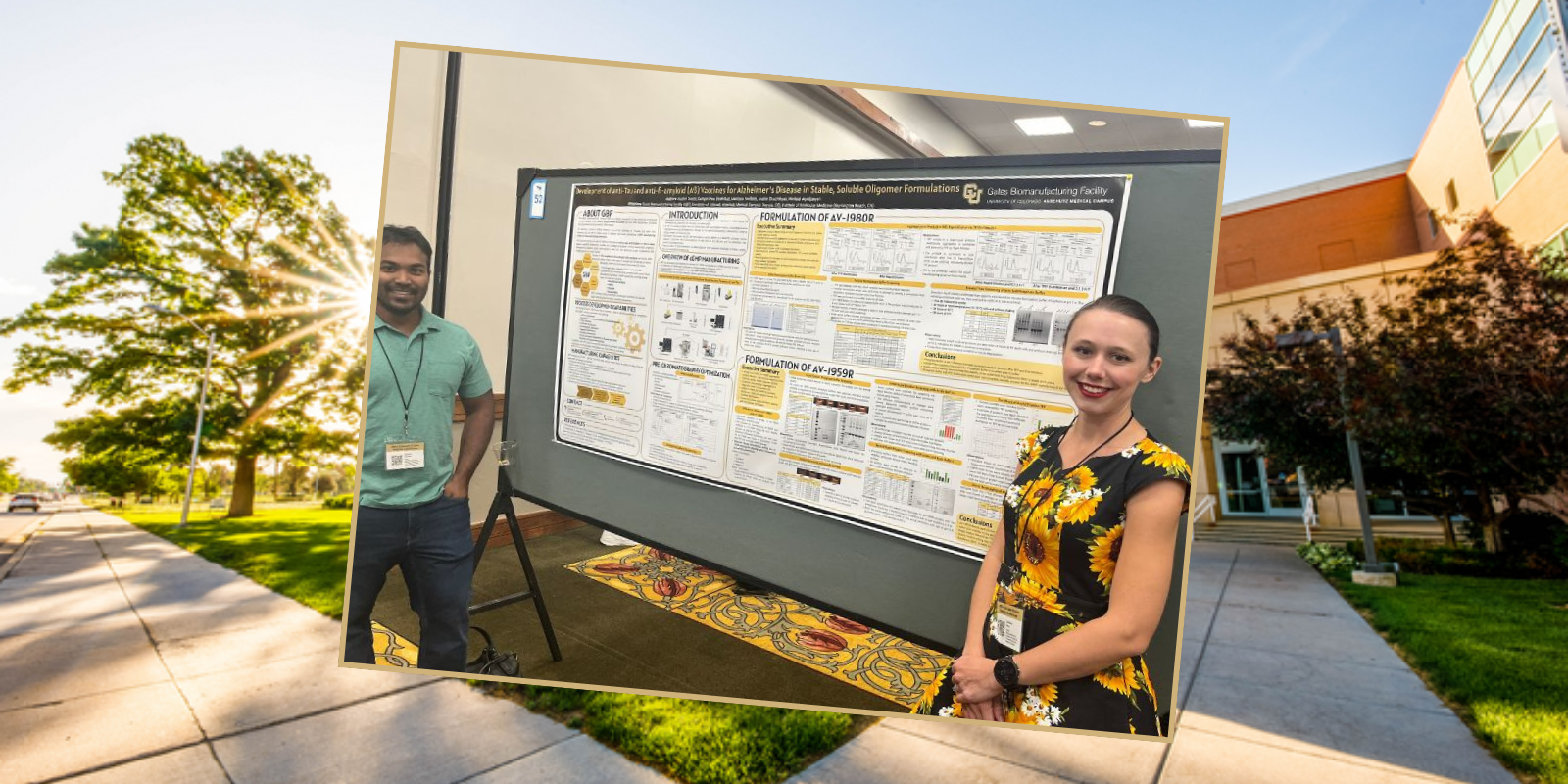

Like many start-ups, the Gates Biomanufacturing Facility’s path to becoming sustainable has been full of twists and turns. The facility, known internally as the GBF, was launched in 2015 with no customers and no jobs in the pipeline, but many capital needs. The visionaries at University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and the Gates Frontiers Fund saw biomanufacturing capabilities as being key to the success of the nascent Gates Center for Regenerative Medicine, and took a leap of faith.

‘Employee No. 3’

Just as cells are the building blocks of life, people are the building blocks of an organization.

Meet Matthew Seefeldt, PhD.

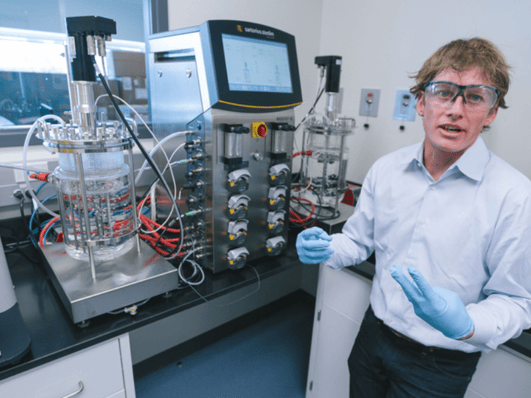

“I was employee No. 3 when I joined the GBF,” said Seefeldt, who earned his doctorate in chemical engineering at University of Colorado Boulder. His career path was also full of twists and turns. He had worked his way through college, even doing a stint between semesters as an undergraduate at Colorado School of Mines at Gates Rubber Co. in Denver, where he applied his chemical engineering skills to improve processes at the plant.

He went on to launch a biologics firm that manufactured a protein for treating multiple sclerosis with his then-academic adviser Ted Randolph, PhD, at CU Boulder in the early 2000s, and had gained a reputation for his expertise in protein “folding,” a technique required to ensure the protein would function properly when manufactured at a large scale.

But that start-up venture ended after taking a molecule through phase 3 clinical trials, and in 2014, he was sought out as a consultant for protein manufacturing at the GBF. The facility had just secured funding and a space in the Biosciences 1 building at the Fitzsimons Innovation Campus.

“All that existed here were the office spaces and cubicles,” Seefeldt said. “The rest of the space was a concrete slab. The job initially was to manage the construction site for six months.”

Dennis Roop, PhD, inaugural director of the Gates Center, recalled that Seefeldt demonstrated his versatility early on, designing and overseeing the buildout of the laboratory suites, selecting equipment, and negotiating contracts. Seefeldt already had experience with investigational new drug (IND) filings and had become an authority on the Food and Drug Administration’s current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMPs), a requirement for manufacturing pharmaceutical products. Seefeldt quickly advanced from a consultant to director of protein manufacturing at GBF. Within a couple of years, he had become knowledgeable about all aspects of the operation.

“As the GBF evolved, it was really Matt who had gained experience in running the whole operation, not only the protein manufacturing side, but also the cell therapy side,” said Roop. “He really proved to be an unbelievably good manager at a time when we needed someone with his expertise.”

In addition, Seefeldt was instrumental in getting external clients in the door, said Roop. “The reality was that with these (external) companies, the technology that they brought in wasn't turnkey. It really had to be developed by Matt and his team.”

In short, Seefeldt was able to sell the value proposition of an academic GMP facility. “We can tell them, ‘We're willing to work with you and help you,’” said Roop. “’We are the experts that can help optimize this technology.’”

Being able to serve external clients has enabled the GBF to ramp up its infrastructure to benefit internal clients – researchers affiliated with Gates Institute -- and to initiate new clinical trials that the University of Colorado sponsors.

Matt Seefeldt, PhD, executive director of the Gates Biomanufacturing Facility.

Navigating highs and lows of a start-up

Although Seefeldt likes to say he saw the opportunity at the GBF as being like a “start-up without the start-up drama,” there were some dramatic moments.

The facility operated at a loss in its first few years, due to the massive investment required for a GMP facility to get up and running. The facility could absorb this cost due to the support from the Gates Frontiers Fund, CU Anschutz Medical Campus, Children’s Hospital Colorado and UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital, who together supported operating costs. As the GBF waited for academic researchers to bring in work, Seefeldt courted external clients.

“Nobody wanted to be the first customer of a new facility,” Seefeldt recalled. In 2016, the GBF onboarded its first external customer, a client with a protein product that was unable to be successfully manufactured by another company.

The next turning point came in 2018, when Gates Biomanufacturing Facility created chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells for another private client. That was followed by CAR T-cell therapy production in collaboration with faculty in the CU School of Medicine for the first-in-human clinical trials at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital and Children’s Colorado in 2020. It was the first cellular immunotherapy project where the developmental science, the regulatory filing and approvals, the manufacturing process, and the infusion of patients in clinical trials were all performed at the CU Anschutz campus.

In 2020, the year the GBF first achieved breakeven financials, Seefeldt was promoted to executive director of the GBF.

When Seefeldt reflects on the ups and downs he navigated at the GBF, he credits his resiliency for seeing him through the challenges.

“It’s a lot like science,” he muses. “Anyone who does a lot of bench work knows, a majority of your experiments won’t work. There are a lot of iterations in early-stage process development. I apply those same strategies to running a business. Eventually the dice roll the right way.”

Note: This article originally appeared in the 2022 Gates Institute annual report. To read more stories about how the institute supports translational research at CU Anschutz, please check out the full report, available online.