Working in palliative care, we are asked to know who the person is, not just about how the illness is presenting in the individual in front of us. Illness reshapes the person and often their loved ones as well. Concepts such as identity, self-worth, relationships and faith are often put to test in the setting of serious illness. For us to do our job effectively and with compassion we need to understand that person and what their personal narrative is. How has illness shaped their life? The following blog is from my friend Brad Carson. He writes as a way to process how serious illness has impacted his life and how he continues to make sense of the cards he was dealt.

~ Darcy Campbell

I always dreamt that my life would be Rockwellian in nature. A romantic slice of Americana that was so simple, pure, and innocent. Instead, the portrait of my life seems more Orwellian. The fantasies of being a great athlete, awe-inspiring performer, transformational leader, or revolutionary haven’t left me, but in the countless aspects of life where my fallacies have failed to materialize, I employed denial to edge myself closer to the idyllic image I falsely wanted and desperately needed to be my reality. Denial took the form of countless dysfunctional modalities, including addiction, codependence, perfectionism, criticism, abusive behavior, relationship sabotage, overworking, and so forth, all of which enabled me to obscure my hellish reality at least temporarily.

Today, I live with two conditions, beta-thalassemia and Primary Immune Deficiency Disease, which the Center for Disease Control (CDC) designates as rare. A rare disease occurs in less than 1 in 50,000 people. Additionally, my bicuspid aortic valve and its subsequent replacement occur in approximately 1 in 50 people. The odds of having all three conditions are 1 in 125 billion. It is estimated that in all of history, there have been 107 billion Homo sapiens who have roamed the Earth.

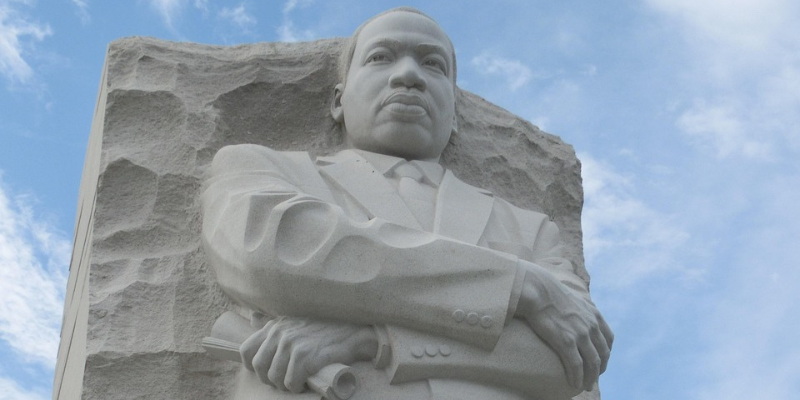

I find myself longing for a new prophetic voice—a voice that is not burdened by the dystopian realities I created for myself. Or maybe it is the person who, having fought the arduous battle of personal demons, has found a way out. Someone who has seen the solution to the problem that plagues us all. I want an imperfect being to stand up in all their fallibility and say, “This is who and what I am, and I am no different from anyone else,” so I can feel validated in all my humanness. The idea that voice may exist within me, that I may be that person who can stand up for himself and tell myself that I am good enough, seems impossibly daunting. The acceptance that the only part of my story that can hurt me is in my denial of my story weighs heavily upon my fragile psyche. Instead of leading the life that was before me and there for the taking, I continued to hold onto an ideal, rooted in fear, shame, and trauma, of some life that was nothing more than an outlandish reaction to the suffering in which I was entrenched. Until I could embrace the life that I was living, I was never going to be happy, nor was it ever a possibility that it was only then that I could begin to lead my authentic life and begin to find connection, love, empathy, and concern for others like I always had wanted but never realized.

When confronting my limitations of physical and mental health, the realities of my origins, and every other human trait I had attempted to suppress, my world of self-reliance came crashing down. I could no longer deny reality. Life is fragile. Life as the sole member of my clan had never worked, and to try to live my life out, I would have to change. This was my dilemma. I had to change. I had to use my voice, and I had to begin to interact with people on a brutally vulnerable and honest level.

The stigma of illness lies in just how terrifying it is for both the people afflicted with it and the people who stand in silence, unsure how to engage appropriately in a compassionate conversation about it. The result often makes the humiliation much more debilitating than the illness itself. Without humiliation, there are treatment options. Without humiliation, there is the possibility of receiving compassion from others and not existing alone. Without humiliation, there is the potential for hope. Sadly, the most challenging part about owning my story and sharing it is having to deal with the discomfort that others experience when they hear about my ordeal. In social situations, if I declare I have a rare immune deficiency disease, people respond with some degree of empathy and usually a vain attempt to understand and show compassion, and they inquire what that exactly means. Sadly, my usual response is to explain it in the easiest way possible, which is to compare and contrast it to AIDS. After I have explained the differences between primary and secondary immune diseases and assured them that I do not have a transmissible disease, I have often watched people take a physical step away from me. At times, I’ve tried to reassure people that my condition is not transmissible and that I’m not contagious; alas, this often makes an uncomfortable situation even more so. Instead, it seems best to keep the explanation rudimentary and skip the AIDS comparison. When it comes to divulging my mental health diagnoses, there is always a moment of trepidation. It is an instant where I ask myself if I want to go through this again and wonder if this person is emotionally resilient enough to hear about the profound adversities of living within my shattered mind. Often, when I present people with the fact that I have bipolar disease, people respond with complete silence. The level of discomfort is palpable. Witnessing other people’s pain is much more complicated than facing our pain. Ours is familiar. Ours is known. We know the limits that each part of our suffering extols upon us. We know it will end at a finite point. Others' pain is terrifying because when people open up and bear their hurt at that moment, you have no idea how far their pain extends. It is pure agony, and you want them to stop hurting so you do not have to experience the incomprehensible embarrassment of watching someone die an emotional death in front of you.

I don’t recall the exact moment, but suddenly, something changed. I came to realize that I am going to die, that I have no control over that fact, and, most importantly, that it is OK. It seems so obvious now. Rudimentary truths of life that, up until that point, I had been unable or unwilling to internalize, accept, and embrace have been incorporated into my psyche. In the end, I had to take death, wrap it around me, and welcome it as a friend. I grant the end is likely not going to be pretty for me, but then death is rarely, if ever, pretty. I realize that dying is easy. Now, the real dilemma hits home, and I’m left with the enormous question of how to live.

I live life as best I can. Some days are better than others. I say I’m good with my health status about 93% of the time. I wear a medical alert bracelet the size of a world championship belt that professional wrestlers wear. Still, there are times when the realities become overwhelming, but they occur in smaller doses, and I have more tools to manage those low points. Daily I make mistakes in my relationships with the people I love. It isn’t always pretty, but much like death, life isn’t always pretty.

Bradley S. Carson

Human Being