You won’t find any ‘Donate to IPF’ options on your dinner tab or at the grocery checkout – yet.

Yet in the U.S., idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is diagnosed in about 48,000 new cases each year and results in about 40,000 deaths annually. Many additional patients are misdiagnosed as having emphysema, frequent pneumonia or other chronic lung conditions. But like its name denotes -- ‘idiopathic’ means ‘unknown’ – no one understood until recently why the lungs scarred so badly that by the time it was detected, it was 100 percent fatal.

Dr. David Schwartz and his colleagues both in the Department of Medicine and across the globe are changing that.

Dr. David Schwartz discusses IPF.

“IPF is when scar tissue takes over the lung. The scar tissue is so extensive, it prevent patients from taking in a full breath,” said Schwartz, professor of medicine and immunology and the Robert W. Schrier Chair of Medicine at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. “The scar tissue prevents the lung from functioning the way it's supposed to. It prevents the lung from moving oxygen from the air into the blood, and it prevents the lung from moving carbon dioxide from the blood into the air.”

Once it's diagnosed, about half of the lung is already lost to irreversible scarring, and will never get better. “Unfortunately, once it gets to that stage it starts to progress much more rapidly,” he said. “And people usually die within three years of diagnosis.”

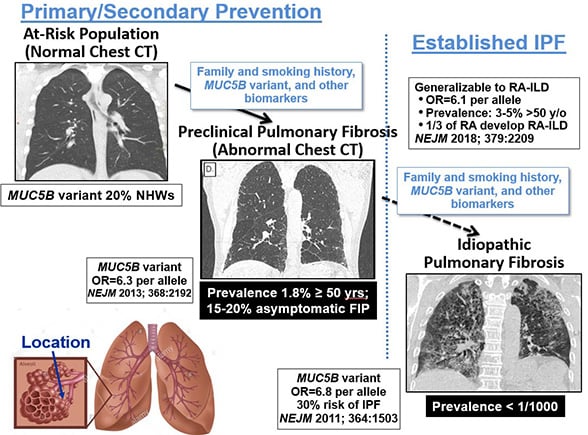

It used to be that male smokers over 50 were thought to be at risk for pulmonary fibrosis – and they are, Schwartz said. However, their groundbreaking research has found specific genetic changes predispose people to develop pulmonary fibrosis.

One prevailing genetic factor

“There's one prevailing genetic factor, which is a gene that produces mucous in the lungs. That gene is over-produced, so you get much more mucous produced than you should,” he said. “By the time a person is 50, they may already have IPF.”

IPF develops over time, and Schwartz believes that the overproduction of the mucous in the smallest airways prevents people with the MUC5B genetic variant (the most important risk factor for IPF) from getting the dust particles and smoke fumes out of the lung. Mucous builds up and weighs down the hair-like cilia in the lungs and keeps them from expelling contaminants from the airways as we inhale and exhale. The contaminants build up and create scar tissue that builds up over many years, and by the time the symptoms become a problem to the patient, the disease is already irreversible.

“People experience a dry, hacking cough, and they can get short of breath even with minimal activity,” Schwartz said. “So, even taking a shower or eating breakfast can make people short of breath. Sometimes just walking across the room will make people short of breath. Certainly walking up a flight of steps make patients with IPF short of breath.”

While only 50 in 100,000 individuals are reported to be diagnosed with IPF, Schwartz’s research indicates far more people have an early form of the disease.

While only 50 in 100,000 individuals are reported to be diagnosed with IPF, Schwartz’s research indicates far more people have an early form of the disease.

“The disease in its mild or early preclinical stage is much more common,” he said. “In fact, it probably occurs in 2% of people older than 50 years of age.”

Schwartz and his team created a global IPF network that includes more than 30 sites and 60 investigators around the world. These researchers have contributed samples of DNA from patients to a global registry; they have collected about 9,000 samples of DNA from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

People of European descent at highest risk

And through these collaborations, they were able to determine another common factor.

“This has been a great resource, because it has allowed us to say that people of European descent are at highest risk, and they're at highest risk because of this mucous-producing gene,” he explained.

Strangely, Schwartz theorizes MUC5B might be a mutation from primitive times that helped stave off respiratory illness and death in children – an evolutionary benefit created by nature to save lives in children that causes disease in older adults.

“When you discover a disease associated genetic change, especially a genetic change that is occurring more frequently in one population, like in this case among Europeans, you have to ask yourself why has it taken off in Europeans, and why is it so under-represented, or less frequently seen in Africans or Asians,” he explained. “The answer to that is that there is probably a beneficial effect producing more mucous in the lung that was experienced by Europeans, and that's why it took off in that population.”

A eureka discovery

A recent eureka discovery has found the gene linked to IPF is also linked to rheumatoid arthritis interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD).

“Patients with rheumatoid arthritis get a disease in their lung that looks just like idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” Schwartz said. “It progresses as quickly as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The MUC5B gene puts people at risk for both of those in the same way.”

And while some researchers of pulmonary medicine have focused on reversing the scarring (only slowing it down in some cases) the team at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus realized they needed to get to the root of the problem long before the fatal diagnosis – even before the scarring begins.

“It's a difficult diagnosis to make, and not everyone is a specialist in being able to make the diagnosis of pulmonary fibrosis,” Schwartz said. “It's important for people who are considered to have pulmonary fibrosis to go to specialty centers where they have the expertise to make that diagnosis.” CU Anschutz Medical Campus is one of those centers, and there are about 50 more across the U.S., he said.

These latest discoveries will make diagnoses easier.

These latest discoveries will make diagnoses easier.

“We can now tell clinicians, relatives of patients are at risk for developing pulmonary fibrosis. And we can use genetic tests to diagnose it earlier before it scars the lungs irreversibly. And, we’re in the process of developing treatments that are focused on MUC5B, on the cause of pulmonary fibrosis,” Schwartz said. “We're trying to use what we have found for earlier diagnosis and gene-specific intervention.”

While there are still many people with this disease who are misdiagnosed or diagnosed after it’s too late, Schwartz and his colleagues are about to change all of that.

“We're using our knowledge about the genetics of this disease to develop a genetic test to diagnose people earlier, to identify who's at risk, to develop treatments that are specific for this mucous-producing gene,” he said.

Shifting to a preventive approach

“I think that we're going to move from a palliative approach to this disease to a preventive approach to this disease,” Schwartz said. “We should be able to diagnose the disease before it destroys the lung, and we’ll be able to treat it and prevent the long-term complications of lung fibrosis and scarring.”

There is no medical program anywhere across the globe specifically dedicated to IPF – yet. But Schwartz and his team of university and global collaborators aim to create such a program at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus.

Schwartz is confident that in another decade there will be drugs – probably an inhaler – that controls MUC5B, stalling the overproduction of mucous -- removing the ‘idiopathic’ from the pulmonary fibrosis diagnoses and saving tens of thousands of lives.

Guest contributor: Cathy Beuten, CU System