Athletes face unique pressures and expectations that can put them at extremely high risk for eating disorders, according to Emily Hemendinger, MPH, LCSW, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

“The temperaments of many athletes are very similar to the risk factors for many eating disorders,” said Hemendinger, clinical director of the Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and Anxiety Intensive Program. “Athletes tend to be high achieving and goal focused, with high attention to detail and high pain tolerance. Moving toward a goal as an athlete is similar to the mechanisms of an eating disorder, such as delaying or restricting food.”

Hemendinger shared these insights at the first Coalition of Athletic Communities for Mental Health conference at CU Anschutz on Feb. 26 and 27.

Culture can foster eating disorders

Athletic teams often focus on the need to constantly improve, such as emphasizing dieting or fasting before a big game. The culture also values “toughing it out, not showing weakness and having it all together,” Hemendinger said, noting that these attitudes also are common in people with an eating disorder. Moreover, if someone is injured and suddenly can’t compete, an eating disorder might fill that void.

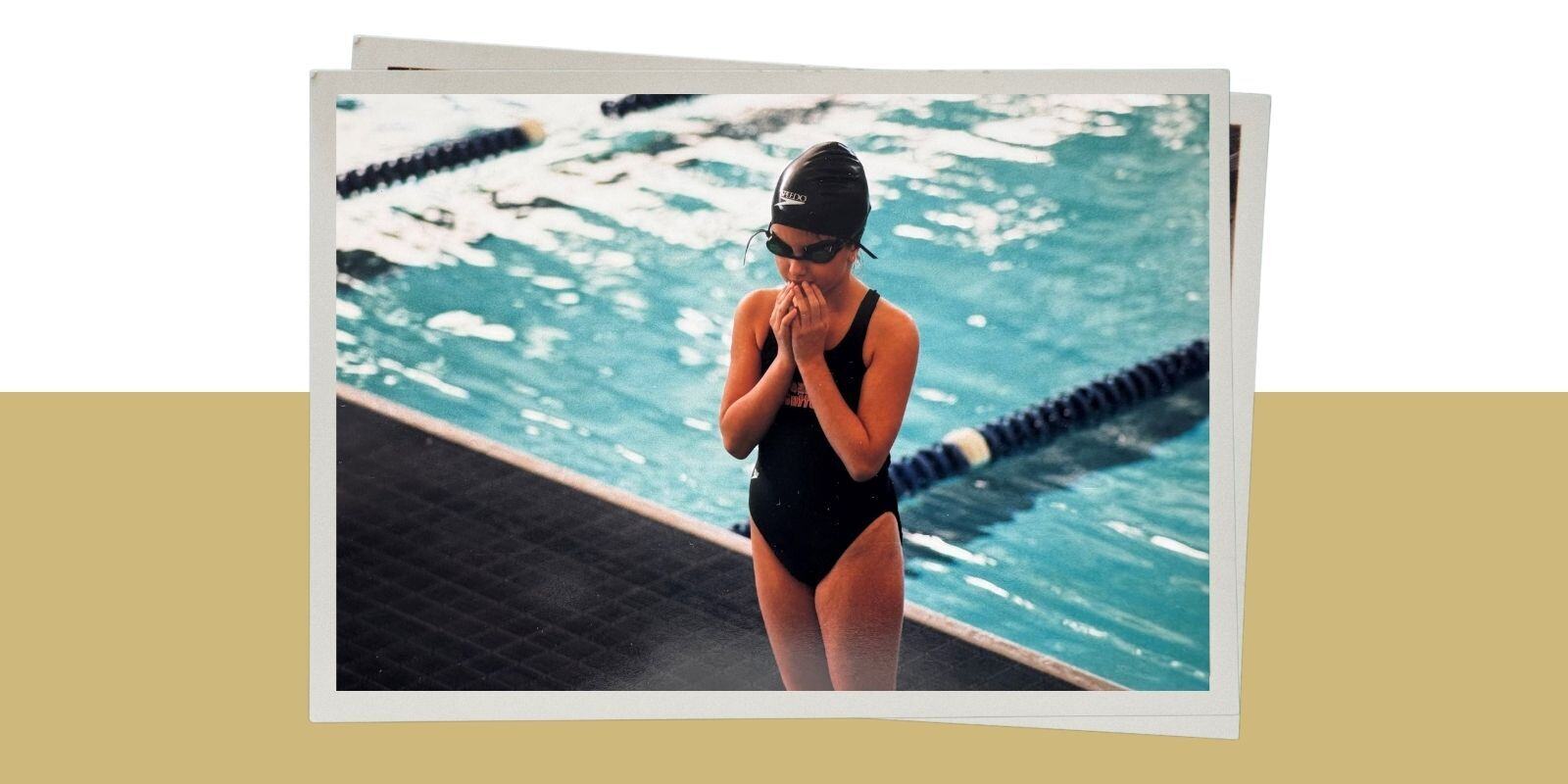

Hemendinger understands eating disorders from personal experience, having developed one as a high school varsity swimmer.

“Other than my family, my coach is one of the biggest reasons why I’m here today,” she said. “When I told him I would no longer be able to swim, he listened, was non-judgmental and held a spot on the team for me. He kept me connected to the team, he held hope for me, even when I didn’t have hope myself, and that was one of the biggest pieces of my recovery.”

Coaching biases can hurt

Coaches and athletic staff should consider how they’re talking about weight stigma and weight-centric practices around athletes. Research has shown that weight bias and fat phobia among coaches can contribute to eating disorders, according to Hemendinger.

“These are things like believing you have to be a smaller size or look a certain way to perform better or faster,” she said.

Types of eating disorders include:

|

But eating disorders are about more than just food and weight. They have biologic/genetic, cultural and psychological causes. The disorder often runs in families, Hemendinger said. Both she and her identical twin developed an eating disorder and have recovered, she for 17 years, her sister for 11 years.

“Not everyone who is genetically predisposed to an eating disorder will develop one, but if they grow up in an environment that is very focused on achievement or appearance or needing to live a certain way, they’re more likely to do so,” she said.

Other contributing factors may include experiencing trauma, a desire to rebel or a need to fit in or please others.

Common and hidden symptoms

Typical symptoms include changes in weight, diet and personality, skipping meals and excessive use of diets and protein powders. But, beyond those, it’s not always easy to tell if someone has an eating disorder, and athletes in particular may have hidden or masked symptoms, Hemendinger said.

Hidden symptoms may include intrusive or repetitive thoughts, secretive eating or exercising, encouraging friends or teammates to eat high-calorie foods that they, themselves, aren’t eating, cooking or baking without eating the food, refusing to try tiny bites of food, excessive interest in being healthy and excessive interest in what others are eating.

Hemendinger also observes behaviors such as increased criticism of self and others, canceling plans, insomnia and apathy. Some people also either avoid water intake or drink excessive water to manipulate the scale for weigh-ins.

“Rigidity in behavior also is a big giveaway,” she said. “For example, people may become super out of sorts if they can’t exercise that day.”

Creating a positive sports culture

Coaches and athletic staff should look beyond weight and vital signs to tell if someone has an eating disorder. They can ask questions like what the person eats in a given day, how they feel about their body and whether they feel like they can take a rest day.

When an athlete is diagnosed with an eating disorder, they may need to take time off from their sport or reduce the time and intensity of participation. Treatment includes medical management, psychotherapy and nutritional rehabilitation.

The athletic community can help reduce the stigma of eating disorders by talking openly about the topic, advocating for systemic change and prioritizing mental health and well-being over athletic performance, Hemendinger said.

“When someone has more of a positive-oriented coaching style, and when coaches, sports personnel and parents don’t give nutritional, weight or body composition recommendations, letting dieticians do that instead, we can have a sports culture that prioritizes mental health and body functionality over body appearance,” she said.

Photo at top: A nervous Emily Hemendinger as a child prepares for a swim meet.

Guest contributor: Carrie Printz is a Denver-based health sciences writer.