Nichol Miller gets good news about her latest CAT scans from Dr. Robert Doebele at the CU Cancer Center. Photos by Trevr Merchant.

Nichol Miller gets good news about her latest CAT scans from Dr. Robert Doebele at the CU Cancer Center. Photos by Trevr Merchant.

Tears stream from behind Nichol Miller's glasses as she studies the latest CAT scan of her torso. Where just four months ago tumors covered both lungs, now only a few tiny dots appear.

"It's a dramatic change," Robert Doebele, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine, CU School of Medicine, says to his patient, who wears a beaming smile.

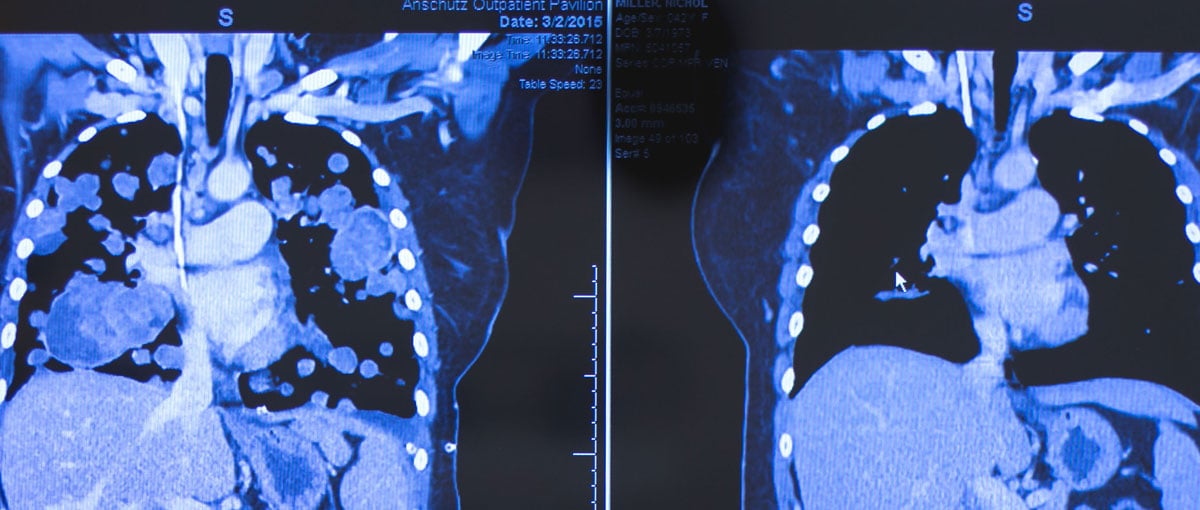

The CAT scan at left was taken March 2, 2015, at the CU Cancer Center when patient Nichol Miller's lungs were covered with tumors. At right is her most recent CAT scan, showing the success of the targeted-therapy drug she is taking as part of a clinical trial.

The CAT scan at left was taken March 2, 2015, at the CU Cancer Center when patient Nichol Miller's lungs were covered with tumors. At right is her most recent CAT scan, showing the success of the targeted-therapy drug she is taking as part of a clinical trial.

Miller, a 42-year-old wife and mother of three, has grown accustomed to seeing improvement during her monthly visits to the University of Colorado Cancer Center, but this scan is especially stunning. "'Dramatic' is such an understatement," she says, reaching for a tissue. "There needs to be a bigger word for the transformation of me (in March) and me now. I kind of always sit around waiting for the other shoe to drop — is it going to continue to work? We're in uncharted waters."

'They need their mom'

Cancer patient Nichol Miller wipes away tears of joy as she meets with Dr. Robert Doebele about her latest test results at the CU Cancer Center.

Cancer patient Nichol Miller wipes away tears of joy as she meets with Dr. Robert Doebele about her latest test results at the CU Cancer Center.

Miller is one of the first patients in a clinical trial of LOXO-101, a targeted-therapy drug developed in a short period of time — just three years, and stemming from another mother's donated cells — through the work of Doebele and his research team at the CU Cancer Center. The drug inhibits a gene, NTRK1 (neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor), that, by fusing to a different gene, results in a mutation that causes tumors.

So far, in Miller's case, the results couldn't be much better.

From week one, Miller has shown improvement on the drug; she currently takes the pill orally twice a day. Just like the shrinking tumors in her lungs, Doebele says, tumor markers in her blood continue to show dramatic declines. Miller updates Doebele on her recent activity: She walked six miles in a Relay-for-Life event and enjoyed a camping trip with her family. "I walked all over — never felt out of breath."

As Doebele elaborates on the test results, Miller's eyes well up again. "It's amazing. It's given me back my future," she says. "I have three kids. They're young — 14, 12 and 10. They need their mom; I need them. I wasn't ready to be done."

'Gave me hope'

Early last March, Miller and her husband drove from their home in Portland, Ore., to Aurora. Miller knew she was dying: Her lungs were filled with tumors, pain radiated through her chest, and breathing was almost impossible without five liters of oxygen per minute.

Her cancer is a metastatic sarcoma that originated in her hip-flexor muscle. She underwent chemotherapy and was to also undergo radiation therapy. But radiation was not an option because too much tissue in vital organs — her small and large intestines — would be destroyed trying to reach the large tumor. The tumor was surgically removed at Oregon Health & Science University in December 2014, but soon it was discovered that the cancer had spread.

Cancer patient Nichol Miller takes a photo of the latest CAT scan of her lungs at the CU Cancer Center.

Cancer patient Nichol Miller takes a photo of the latest CAT scan of her lungs at the CU Cancer Center.

Lara Davis, MD, an oncologist at OHSU, recommended that Miller participate in the LOXO-101 clinical trial at the CU Cancer Center. "Coming here was our hail Mary," Miller said. "Everyone here — doctors, nurses, the entire staff — has been amazing. Through the whole process they gave me hope."

As test results kept coming out positive, it dawned on Miller that she could start to make plans again with friends and family. "I can make plans for two, three years down the road, it feels like," she said. "It's not the inevitable like it was in March."

A mother's legacy to another

The medical journey that has given Miller hope actually began three years ago.

In 2012, Doebele was treating a 46-year-old never-smoker who had metastatic lung cancer. Unfortunately, at the time, there were no drugs available or even in clinical trials that could treat the patient, also a mother of three children. Before she died, the patient gave Doebele a sample of her tumor to grow an immortal cell line that could be used for further research and to test drugs against this type of cancer.

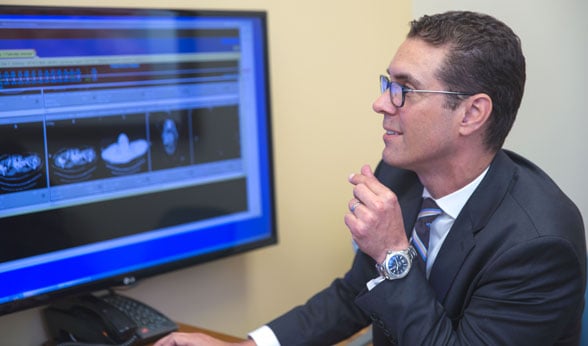

Dr. Robert Doebele studies the latest CAT scan of patient Nichol Miller, showing her lung tumors have dramatically shrunk.

Dr. Robert Doebele studies the latest CAT scan of patient Nichol Miller, showing her lung tumors have dramatically shrunk.

In a broad search of hundreds of potential cancer-causing genes his team found the abnormal gene NTRK1 in her cancer. "That really accelerated the development of drugs that can treat this type of tumor, because that was the initial proof we needed to convince companies to pursue these drugs in clinical trials," Doebele said. "We're really grateful that this patient's allowance to use her cells has really helped another young mother treat her cancer better, and hopefully will help many, many patients in the future."[perfectpullquote align="left" cite="Dr. Robert Doebele" link="" color="" class="" size=""]"We're really grateful that (a previous) patient's allowance to use her cells has really helped another young mother treat her cancer better, and hopefully will help many, many patients in the future."[/perfectpullquote]

A local pharmaceutical company — Array Biopharma in Boulder — produced a drug that showed promise in blocking the activity of this gene. Loxo Oncology, Inc., subsequently acquired the license to conduct clinical trials using the drug; the trial began in 2014, with the CU Cancer Center being the closest trial site to Miller's home in the Pacific Northwest.

Targeted cancer therapies give physicians confidence of their effectiveness, while offering the added benefit of reduced side effects, Doebele said. "We're actually matching the drug to the patient's tumor, and when we use this strategy, we can expect that patients have probably a 60 to 70 percent chance of a dramatic tumor shrinkage and probably about a 90 percent chance of having control of their tumor in some ways," he says. "Whereas with chemotherapy, the percentages range from 10 to 20 to 40 percent at most."

Doebele said other patients with the NTRK1 gene are starting to enroll in the clinical trial, which is explained in detail here. He is hopeful that within a couple years the current trial of LOXO-101 will lead to a drug physicians can prescribe.

Genetic testing is critical

Miller underwent extensive genetic testing which allowed physicians to identify the abnormal gene in her tumor. The NTRK1 mutation occurs in a small percentage of many different cancers, Doebele said.

"It speaks to the issue of the importance of getting broad genetic testing because it may be that a sarcoma, lung or breast cancer — or any type of cancer — can probably have this type of alteration. And we won't know unless we're testing," he said. "The old paradigm was that a mutation in a particular gene would only happen in one type of cancer, but that's not really true anymore."

Through it all — including the grim period just four months ago — Miller has maintained a bright outlook. "I believe being positive has a lot to do with how things pan out." She now has her sights on taking her children to Disneyland, traveling to see family members in the Midwest, and going on a cruise with her husband to celebrate their 15th wedding anniversary next year. "We never had a honeymoon."

Also high on the list is a plan to finish her training to become a licensed lactation consultant.

'I have a future'

Miller is currently enjoying relatively smooth sailing — albeit in the "uncharted waters" of a clinical trial. Doebele says solid tumors remain difficult to cure unless they are caught at a very early stage. Long-term control of these types of cancers is becoming increasingly feasible through multi-drug treatments.

Patient Nichol Miller gives her physician, Dr. Robert Doebele, a hug after receiving good news about how much her lung tumors have shrunk.

Patient Nichol Miller gives her physician, Dr. Robert Doebele, a hug after receiving good news about how much her lung tumors have shrunk.

"This is a rapidly emerging field that allows us to test patients' tumors and perhaps identify this gene or other genes that may allow them either FDA-approved therapies or clinical trials that are very likely to help them control their cancer," Doebele says. "I think a lot of us think about HIV as a model. Although we're not typically curing HIV with multi-drug regimens, we are controlling it for decades so that people can live a relatively normal life. So I think that might be a closer goal."

After her most recent clinical update, an elated Miller steps into a CU Cancer Center hallway to call family members with the good news. She tells her ecstatic husband about the tumors that are now barely visible on the CAT scan. "They're like specks," she says.

As the dots shrink in her lungs, Miller sees more life unfolding on her horizon. "It was during these last couple months when we started to see this dramatic change — this amazing change — that it really hit home: I have a future again."