How have the American Indian and Alaska Native communities handled the COVID-19 pandemic? Have the mask mandates and vaccines been met with the same sort of resistance that we have seen elsewhere?

If you had interviewed me in November of 2020, before the vaccines rolled out, I would've reported a great deal of pessimism and angst about vaccination hesitancy in American Indian and Alaska Native communities.

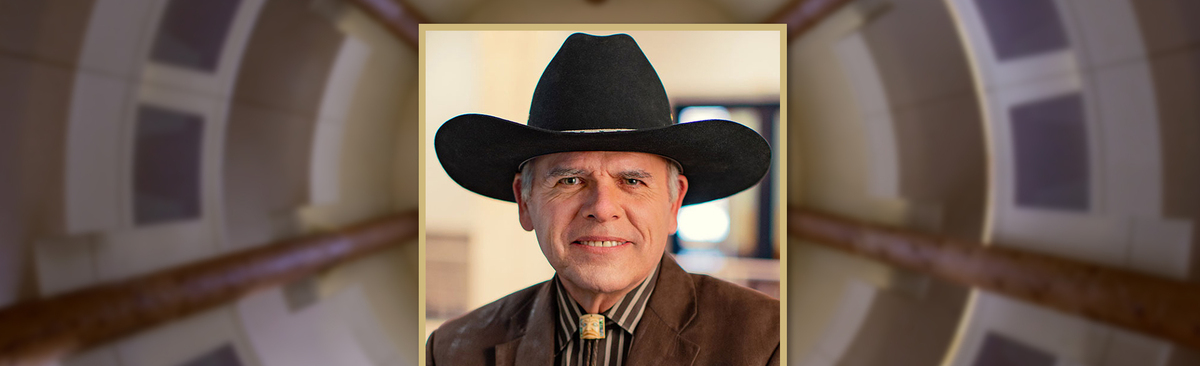

But because of local champions in our communities and formal as well as informal leadership, the rates of vaccination among Native people far exceed the general population. And these same communities adhere to mitigation practices much more frequently than their non-Native counterparts. The pandemic has been an opportunity to mobilize our core values. We believe in individual as well as collective responsibility for caring for others in our communities, notably elders, the ranks of which I recently joined, having turned 71 in May.

This does not deny the impact of social determinants of health on Native people, which have led to incredible exposure to the virus, to the severe health consequences of contagion, to challenges in accessing necessary care, or mortality which is substantially higher among us, as it is for other racial and ethnic minorities, than the population in general. But I’m very proud of how my communities have reached out and engaged others in battling the COVID-19 pandemic.

What do you think is the most pressing mental health issue for the American Indian and Alaska Native communities?

Several major mental illnesses challenge our lives today. The first is depression. For many American Indian and Alaska Native communities, historical trauma, structural racism, crushing poverty and reduced opportunities to improve our lives introduce a collective sense of depression. Events like the pandemic amplify the consequences of this substrate of emotion and psychological distress. Depression is followed closely by post-traumatic stress disorder, which arises in response to events out of the normal range of human experience which in turn triggers a series of adverse life experiences. The pandemic certainly qualifies as such an event.

One consequence of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, and why addiction is such a concern in Native communities, is we often self-medicate. We turn to alcohol or other substances to try to reduce the pain, to alleviate the suffering, to temper the lingering and lasting effects of mental illness on our daily lives. This is a fairly simplistic, but robust way to understand the interplay among mental illness and addictions among my people.

Mental illness has long been stigmatized in Western society. Does that stigma also exist in the attitudes of American Indians?

When I entered the field 43 years ago, addiction – alcoholism for the most part at that time – and mental illness were both highly stigmatized. Today that's not the case with addiction. Why? Because leaders in our community who had been addicted to one substance or another stepped forward to share their journeys of recovery and the factors critical to their success. Their fearlessness enabled us to engage in conversations we had previously avoided, and began to de-stigmatize addiction. We realized people should no longer believe they are alone. We came to realize addiction isn’t necessarily a part of our destiny.

We've come a long way toward de-stigmatizing addiction and alcoholism. Unfortunately, this is not as true with respect to mental illness. As recently as 15 years ago, while interviewing Vietnam combat veterans in tribal communities, one Marine from the Southwest said to me, “I'd rather be thought a drunk than crazy.” His words captured the difference and underscored the stigma that remains prominent today. There are attempts at the local level to de-stigmatize mental illness. We've become more adept at doing so in regard to child abuse and neglect, domestic violence, elder abuse and neglect, and other kinds of chronic ailments, like diabetes and cardiovascular disease. But Native people’s feelings about mental illness have resisted such change.

How do treatment methods differ when dealing with mental health issues among indigenous communities compared to other groups?

There can be substantial synergy between biomedical and traditional forms of healing. Many Western forms of treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and pharmacological interventions, are effective in helping Native people address mental health problems. However, we face several challenges in this arena. The models we've had for delivering mental healthcare in Native communities are largely office-based. This approach is limiting and is simply ill-advised in tribal communities, especially given the nature of our lived experience and sense of collective identity. An exclusive focus on the individual, whose care proceeds in isolation, separate from the broader social structure and emotional supports, ignores therapeutic resources that can provide additional leverage to render even biomedical treatments more effective.

But we’ve also come to realize other forms of treatment are available to us in terms of Native cultural values and practices which were once criticized, castigated, even outlawed. Practitioners, policymakers, and funders alike are recognizing their potential effectiveness and benefit. It's not that one type of approach to treatment should replace another, they can complement and strengthen one another. We are becoming more deliberate and thoughtful about how we can offer comprehensive, continuous care that draws upon the strengths of the wide range of available treatments, whether biomedical or traditional in origin.

The pandemic sparked a mental health crisis in this country with many reporting depression, anxiety and increased drug use. How has this mental health crisis played out among American Indians?

Our vulnerabilities are no less than others, of course. Dr. Dedra Buchwald, a colleague from Washington State University, and I had the opportunity on April 9 to present to President Biden’s COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force. They asked us specifically to present in regard to the behavioral health consequences of the pandemic on American Indian and Alaska Native people. We documented for them its enormous consequences: among them increased rates of depression and risk of suicidality. The pandemic has reawakened post-traumatic stress disorder, individually and collectively, in our communities, dating back to the devastating epidemics that have afflicted Native communities for more than one and a half centuries.

Even those of us who have escaped the virus suffer indirectly its deleterious effects. Chronic health conditions, like diabetes or cardiovascular disease and their complications, such as end-stage renal disease and amputations, are particularly common among Native people. The pandemic has dramatically reduced the availability of primary care and other services necessary to manage these chronic conditions, increasing morbidity and mortality. Yes, the pandemic has definitely heightened the adverse mental health consequences among American Indian and Alaska Native communities.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

Among tribal communities, there is a common refrain: “The honor of one is the honor of all.” In my acceptance speech of the Sarnat Prize award on October 17, I emphasize the National Academy of Medicine’s recognition is not for my achievements alone. The impact our work represents the collective effort, personal as well as professional, of many people over the last four and a half decades. In honoring me, the academy, honors all who contributed to this endeavor and recognizes the major advances we accomplished together, today, in tribal communities.