People with Down syndrome are more likely than the general population to develop serious respiratory infections. Often, symptoms are so severe that patients require hospitalization. As respiratory season moves in, researchers on campus are working to understand what unique genetic factors may contribute to this problem.

“Down syndrome is caused by the triplication of chromosome 21, and we really don’t fully understand the extent of how it impacts lung biology,” said Brian Niemeyer, PhD, research associate with the Linda Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “We know the immune system doesn’t function as well among individuals with Down syndrome, and we know there are some physical differences in the basic structure of their airways.”

Teasing out the reasons why may help researchers discover new strategies for preventing and treating these infections. Niemeyer and colleagues published a study in the journal iScience that analyzed differences in the lungs of those with Down syndrome. The study was a collaborative effort with the Crnic Institute, the Benam Lab at the University of Pittsburgh and the García-Sastre Lab at the Icahn School of Medicine.

The study assessed two main areas:

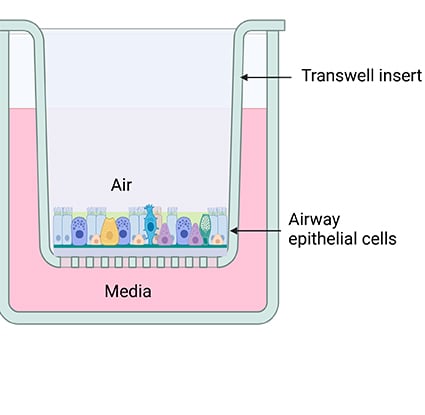

- how normal lung biology changes using a model of Down syndrome. Researchers examined how the distribution of cell types in the lung and length of cell function change homeostasis (stability in physical processes). This first part was done without any virus exposure.

- how the cells from the Down syndrome model respond after they have been exposed to a respiratory virus, like influenza.

These two approaches helped researchers see how the cells look normally and how they look when responding to a live infection.

Niemeyer, the study’s co-lead author, shared more about his team’s findings and their implications in the Q&A below.

.png)

.jpg)