After being diagnosed with cancer of the intestines in November 2016, Nick Gonzales was in and out of the University of Colorado Hospital (UCH) over a period of several months. By the time he began receiving palliative care, Nick and his wife Carol were stressed by multiple hospital visits and struggling to process his declining health.

They found relief through supplies you might not expect to find at a hospital—colored pencils and a camera.

Learn More |

|

For information about the Creative Arts Therapy Program, contact Jean Kutner: Jean.Kutner@cuanschutz.edu To learn about ways to give, contact Liz Muscatello: 303-724-6545, Elizabeth.Muscatello@cuanschutz.edu |

The Gonzales family participated in the Natalie Kutner Palliative Care Creative Arts Therapy Program, one of UCH’s newest approaches to care for people with serious illness. According to Program Director of the UCH Palliative Care Service Jeanie Youngwerth, MD, the program combines “the creative arts with therapy to make a patient feel like a person again.”

Nick and Carol used coloring and photographs taken by their art therapist to discover how creating art enables a patient to express deep and difficult feelings. “Poetry, art and music—they help to get your feelings out,” Nick Gonzales said. “It’s motivating, and I expressed more when I got involved with the program.”

His wife Carol agreed. “For me, coloring releases the stress of being in the hospital for so long.”

A personal connection to palliative care

The Natalie Kutner Palliative Care Creative Arts Therapy Program was created to honor the memory of Natalie Kutner—artist, medical social worker, Parkinson’s patient and the mother of Jean Kutner, MD, and CU Anschutz School of Medicine Professor of Medicine. Jean Kutner serves as a physician on the UCH palliative care team, and she played an instrumental role in starting the program.

Although she was already a palliative care physician when her mother’s health began to decline, being a family member of a terminally ill patient expanded Kutner’s perspective. “As a relative, I gained an even deeper appreciation of palliative care,” Kutner said. “The care team provided an extra layer of support that our family relied on.”

Untitled (House) by Natalie Kutner

In the final stages of her disease, Natalie Kutner received eight months of palliative care. When Natalie died, Jean Kutner and her father designated the memorial donations for palliative care. Those funds and a generous anonymous donation made it possible to expand palliative care at UCH to include creative arts therapy.

Establishing a creative arts therapy program in Kutner’s honor resonated with her family because of Natalie’s volunteer work in the community and her legacy as an artist. When discussing her own work, she described the power art has to “transmute the ordinary into the extraordinary.”

Creators, not ‘reactors’

A similar transformation occurs in creative arts therapy at UCH, which helps patients cope with the existential pain of a terminal illness and communicate with their loved ones. “The program is an interdisciplinary approach to decreasing suffering and clarifying meaning,” Youngwerth said. “The therapists weave their skills and knowledge of art and music into their counseling and therapy.”

Palliative Care Art Therapist Amy Jones and Music Therapist Angela Wibben maintain a well-stocked “Art Cart” and an ample supply of musical instruments for patients and families. “Sometimes patients have difficulty coping, overly identify with their disease or worry about leaving their children and grandchildren,” Wibben said. “Creative art therapy expands their definitions of themselves.”

Patient art becomes part of the legacy they leave for their families. One young mother with cancer constructed a bird’s nest out of weaving materials. She included a ceramic egg for each of her children and pebbles to represent the years she spent with her husband. “Creative art therapy looks at a person’s whole life,” Jones said. “It looks for metaphors that ease suffering beyond the reach of words.”

Wibben agrees. “Experiential music therapy may begin by listening to music and lead to a conversation that reveals what music means in our lives,” she said. “That might lead to songwriting, which makes the patient a creator, not a ‘reactor.’”

Turning a life into a legacy

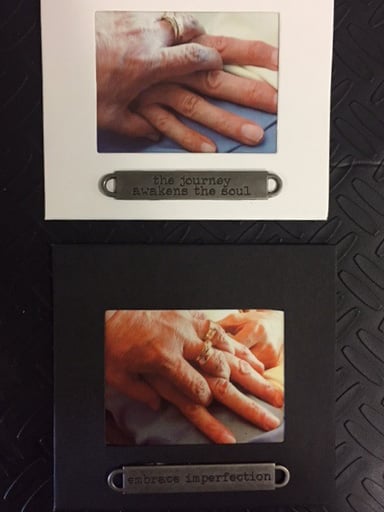

Photographs of Nick and Carol Gonzales' hands, taken by their art therapist Amy Jones

For Nick and Carol Gonzales, the couple found art creation to be relaxing, but their therapy also brought them closer together. When they left UCH, they took their artwork, as well as Jones’ photographs of Nick and Carol’s hands.

The photographs are a part of Nick’s legacy. “The pictures are really expressive,” Carol Gonzales said. “Seeing his hand over mine—I think of how he protected me.”

“Palliative care is not just medication, it’s emotional and spiritual help,” Nick Gonzales said. “When you share, it helps to heal. I look at those pictures of our hands, and I think of Carol and me taking care of one another.”