Getting ready to catch a morning flight to Chicago in February 2018, Emily Daniels felt a strange tightness in her chest. She noticed a shortness of breath. Taking her mother’s advice, she called her obstetrician who said she should go to the ER.

She remembers thinking, “Emergency room … is that really necessary?” Nonetheless, Emily went to an ER near her home in Lakewood and re-booked for a 5 p.m. flight, thinking she’d still make her business trip. After an initial test, doctors advised a CT scan, which revealed two blood clots in Emily’s lungs and a mass in the bottom of her right lung.

“Cancer didn’t even register in my mind,” she said. “What could that (mass) be? I’m young, healthy, no history of disease, never smoked.”

The doctor said it could be lymphoma, a virus or lung cancer and said she should remain in the hospital. Adding to the urgency: Emily was 33 weeks pregnant with her second child.

‘Fight for our kids’

A subsequent biopsy confirmed the mass was cancerous and additional scans showed cancer in Emily’s bones and right adrenal gland. Stage IV lung cancer.

“Initially, it was shocking, devastating,” she said. “But we (along with her husband Brian) also knew we couldn’t wallow in our sadness. We had a 3 ½-year-old girl (Paige) and a baby on the way, so we were going to fight for our kids.”

Emily stayed in the hospital and delivered her baby, Brady, but her diagnosis precluded the new-mother things, like nursing and a quick release from the hospital, she enjoyed with Paige. What should have been a celebratory time felt overshadowed by a startling and grim diagnosis.

She remembers the trip home from the hospital with Brian – Paige was at home with Emily’s parents – where “we pulled over on the side of the road and broke down.”

Pivotal decision for personalized care

Brian Daniels, a former football standout at the University of Colorado, consulted a handful orthopedic doctors he knew from his playing days. Their advice: Get an appointment with Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, professor and director of thoracic oncology, at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. “He’s one of the best in the world with this targeted therapy,” Emily said. “It was a no-brainer … this is where I needed to do my treatment.”

Dr. Ross Camidge

The decision has proven to be pivotal, as Camidge, in collaboration with Robert Doebele, MD, PhD, associate professor of medicine, CU School of Medicine, eventually devised a completely novel and personalized treatment that has, for more than eight months, stopped the spread of Emily’s cancer.

However, before making this major discovery, which will be presented at next week’s World Conference on Lung Cancer in Barcelona, Emily’s medical team worked through their clinical bag of tricks in a very short time. In the ensuing battle, it was readily apparent that Emily’s cancer did not play by the normal rules.

Targeted therapies

In basic terms, the cancer battle comes down to exposure and attack: identifying the genetic pathways that enable cancer to grow, and developing therapies that inhibit those pathways.

BREAKTHROUGH ON WORLD STAGE |

| Camidge and Doebele are co-authors on the report about the living-cell line that gave doctors insight into Emily Daniels’ cancer and resulted in her novel, personalized treatment regimen that will be presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer in early September. |

Soon after Emily was first seen in the lung cancer multi-disciplinary clinic at the CU Cancer Center Camidge quickly discovered that she had ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Over a decade ago, Camidge was on the clinical-trial forefront that developed the first treatment for lung cancers driven by acquired changes in the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene, causing the cells to grow abnormally fast and aggressively.

A few years later, the initial drug was replaced by more effective ones; Camidge co-led an international trial in 2017 that established alectinib as the initial go-to therapy for this sub-type of lung cancer.

In late-February 2018, Emily started on alectinib and initially responded well to the four pills taken in the morning and four more in the evening. But in just a couple months, her cancer was progressing again.

Another biopsy, tested with the CU Colorado Molecular Correlates Laboratory’s cutting-edge assays, did not show any identifiable reason for the cancer’s resistance. Camidge tried another ALK inhibitor, brigatinib – a drug he also helped develop and one that showed great promise for longer-duration disease control.

Dr. Robert Doebele

However, within a month, Emily’s cancer was progressing again.

Living cells are key to breakthrough

In June 2018, the addition of a specific chemotherapy regimen, identified by Camidge in 2011 as being particularly effective in ALK-positive lung cancer, helped stop her cancer – but only for 3 ½ months. The team then applied another CU-developed treatment strategy: weeding the garden – or radiotherapy treatment of “oligo-progression” as Camidge’s team coined it – whereby they kept Emily on her drug treatments while treating individual spots of cancer with highly focused radiation.

However, nothing completely slowed the cancer. “My colleague Dr. Bob Doebele had this idea that not everything driving resistance in a cancer cell can be found just by looking with the already-established tests,” Camidge said.

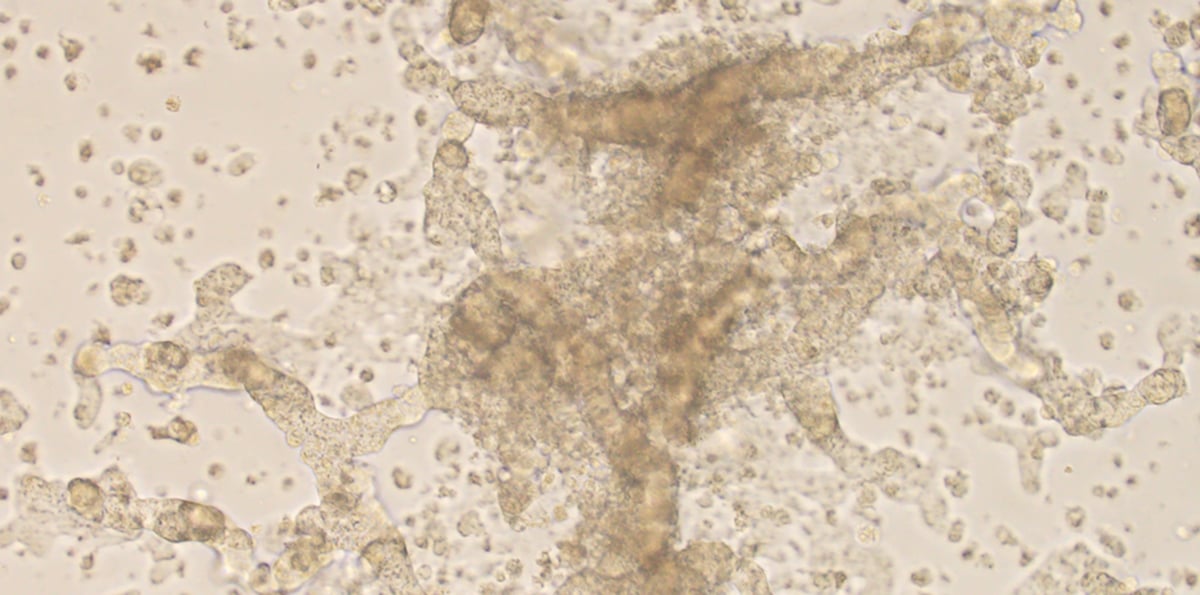

Doebele knew there were only a certain number of interrogations that could be done on the kind of preserved pieces of tissue from biopsies like the one sent to the Colorado Molecular Correlates lab. So when the biopsy of Emily’s cancer was taken, as part of a CU research protocol, some of her cancer was sent directly to Doebele’s lab to see if live cancer cells could be grown from it.

“When Bob grows it and it’s living, he can poke it and see which signaling pathways go up and down,” Camidge said. “He was able to deduce that Emily’s cancer had become dependent on another signaling pathway, separate from the ALK side of things.”

That pathway is called MET, and it essentially acts as a second driver of Emily’s cancer.

‘Responded like a dream’

Importantly, all of the known ways of activating MET, the methods doctors test for it in preserved cancer tissue, showed normal results. The key difference were the living cells.

This is a photo of Emily Daniels' living cancer cells studied in Dr. Robert Doebele's lab on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus.

“Entirely because Dr. Doebele was able to grow the cells in a lab, we were able to say for the first time to a patient, ‘Look, your cancer cells have tons of MET signaling going on,’” Camidge said. “In the living cell lines, if we put on a MET inhibitor as well as an ALK inhibitor, they get really unhappy.

“Emily is technically the only patient I know of that has this exact mechanism resistance,” he said.

‘I just have to have hope and believe that the doctors are going to keep coming up with new things.’ – Emily Daniels

Based on Doebele’s data, which will be highlighted at the Barcelona conference, Camidge added crizotinib, a licensed drug designed for other purposes but which can function as a MET inhibitor, to Emily’s treatment.

What has been her response to this targeted-therapy regimen — one that’s been applied to a handful of patients, if that, in the world? Emily started the regimen last December and “she has responded like a dream,” Camidge said.

Patient advocate

Emily, 33, is enjoying every day with her children, watching Paige head off to kindergarten and hearing Brady utter his first words. In August, she and Brian took a long-planned trip to the French Alps and coastal Italy. Every chance Emily gets, she logs a several-mile run, does yoga or lifts weights.

She has also become an advocate for other people battling the disease. She and Brian organized a golf tournament – Links for Lungs – which tees off again on Sept. 11. Last year’s debut tournament raised over $130,000 for the Lung Cancer of Colorado Fund.

“It’s important for me to be an advocate for research and be the face of lung cancer,” she said. “This can happen to anyone – it’s not just smokers and older people.”

‘Truly cutting edge’

Emily said she need not look beyond the CU Anschutz Medical Campus and UCHealth University Hospital for her care. “The research is truly cutting edge,” she said. “They’re doing things at the hospital that they’re not doing at other places. The research that Dr. Doebele and Dr. Camidge are doing truly saved my life and gives me unique treatment options.”

‘Here we are at the cutting edge again. Our whole team lives there and we’re comfortable with it.’ – Dr. Ross Camidge

Camidge is impressed by the way Emily has turned her disease into a positive as she reaches out to other lung cancer patients. “Even though she’s hit many bumps in the road, her attitude is kind of like, ‘Yeah, it’s just another one,’” he said. “So she’s actually much more inspiring to them – not necessarily because things have gone well, but because she’s dug in there… It’s like, she can really say to other lung cancer patients, ‘We’ve been through it, and I know what you’re going through.’”

Emily knows she’ll never be completely cancer free; she has to stay on treatment to control the disease. The important thing is to keep moving forward. “I just have to have hope and believe that the doctors are going to keep coming up with new things,” she said. “I want see Paige go to kindergarten, and Brady grow up and play football and do all the things a parent wants to do with their kids.”

Camidge said all indications show that the combination therapy is working in Emily’s case, but they must remain vigilant.

What’s next?

The next move is to develop a clinical trial with a MET inhibitor that is better at getting into the brain than crizotinib. “The brain is known to be a problem area for crizotinib to reach,” he said. “So we are not waiting to react; we are working on developing the next generation of MET-ALK combinations for Emily and anyone else who needs them.”

The research into cancer’s vulnerabilities, to ideally overcome the disease, grows ever stronger, thanks to the fundraising efforts of people like the Daniels and the novel clinical trials taking place at academic medical centers such as CU Anschutz.

“Here we are at the cutting edge again,” Camidge said. “But that’s OK. Our whole team lives there and we’re comfortable with it.”

.png)

.jpg)