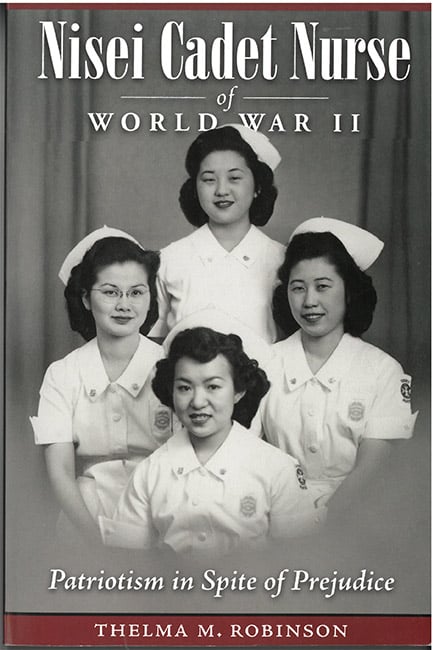

During World War II, Japanese Americans were shipped to internment camps throughout the US. American-by-birth citizens of Japanese parents (Nisei) loyally answered the call for new nurses. Despite numerous obstacles to attain a nursing education, these courageous young women overcame prejudice to volunteer for the US Cadet Nurse Corps and serve in American hospitals. The University of Colorado School of Nursing was a safe haven for many Nisei students who were turned away from nursing programs on the west coast.

One such nurse was University of Colorado School of Nursing alumna Suiko Kumagai who made a career out of the service. Her story was originally published in Thelma Robinson’s book titled “Nisei Cadet Nurse of World War II” and is reprinted below.

“Nisei Cadet Nurse of World War II” by Thelma Robinson |

The US Cadet Nurse Corps…World War II… Hiroshima…Korea…Vietnam – names we find in history books! But for Suiko “Sue” Kumagai, they are the highlights of a nursing and military career. Sue, a Japanese American nurse, committed her life to military nursing and serving Uncle Sam both here and abroad, including the country of her ancestry. Sue said she made two decisions early in life: one was that she would not marry, and the other was to commit her career to military nursing. She said, “I married Uncle Sam.”

Sue Kumagai was born January 23, 1920, in the farming community of McClave, Colo. Her father came to the US from Japan in the early 1900s to work on the railroads. A few years later her mother joined him. Around 70 families settled in the rich Arkansas Valley in Colorado to engage in farm work.

Sue was the youngest of nine children. Her mother died shortly after she was born, and her father died when she was four years old. A farm friend who had just lost a baby raised Sue until she was four. When an older sister, Toki, married at the age of 17, she took over the parenting role.

In addition to going to public schools, Sue attended Japanese language school on Saturdays. When she was 19 years old, she decided to leave the farm to join Japanese American laborers working in the citrus groves of California. Her first job was to pack oranges and lemons, but she didn’t make much money because she was too slow. She had better success at doing housework. Later that year she moved to Cheyenne, WY to be near her sister and found work as a “school girl.” In the 1930s, intelligent hardworking Japanese American girls and boys were in high demand by families who would give them work in exchange for a small salary, board and room.

When Sue’s employers moved to Denver, Colo., she asked to move with them. Sue had her own basement apartment and continued her school girl work. She earned $8 a week and had Sundays and Thursday afternoon off. “About 20 Japanese American school girls lived in the Denver area, and we enjoyed each other’s company on our day off,” Sue said. “We even had our own baseball team.”

One day a neighbor, a nurse at Denver General Hospital, asked Sue what she was going to do with her life. At that point Sue hadn’t decided but knew that she needed to learn a trade so she could support herself. The nurse friend suggested that Sue consider nursing, in which she could get her education by working and learning at the same time. Sue had not pondered nursing as a career. The neighbor explained that the Colorado Training School based at Denver General Hospital offered a chance to learn a profession. If accepted into the program, the school would provide hospital student uniforms, room and board, and a small stipend in exchange for working on the wards while studying to be a nurse.

The neighbor brought Sue an application. She found that she met all the requirements except for chemistry. She signed up for the course through Emily Griffith Opportunity School and went to class on her afternoon off. After completing the course, the director of nurses said, “Well, you met all the qualifications. I guess I’ll have to admit you.” The director gave Sue the impression that she didn’t like her.

Sue was now a full-fledged student nurse, but it wouldn’t be easy. This was 1941 and on December 7, the country of her ancestry bombed Pearl Harbor. Sue and three other Japanese American student nurses were called into the director’s office. She told them that they could stay but they had to prove themselves. The FBI came and checked the Nisei nurse students for contraband (flashlights, cameras, and knives). Sue was determined to stay and tolerated those who called her a “Jap.”

During her senior year of training, the US Cadet Nurse Corps became available, and Sue joined. She said that she didn’t get a uniform. Only the Caucasian student nurses assigned to Fitzsimons Army Hospital were allotted the snappy gray uniform trimmed in scarlet.

Sue visited her sister and her sister’s six children who were interned at Amache, the War Relocation Center in Colorado. Sue said, “I made my sister nervous as I was defiant to the guards.” Her sister asked her to include candy in the care packages which she sent on a regular basis to supplement the meager camp existence. Packages were censored before they reached the internees, and Sue’s nieces and nephews never got the candy.

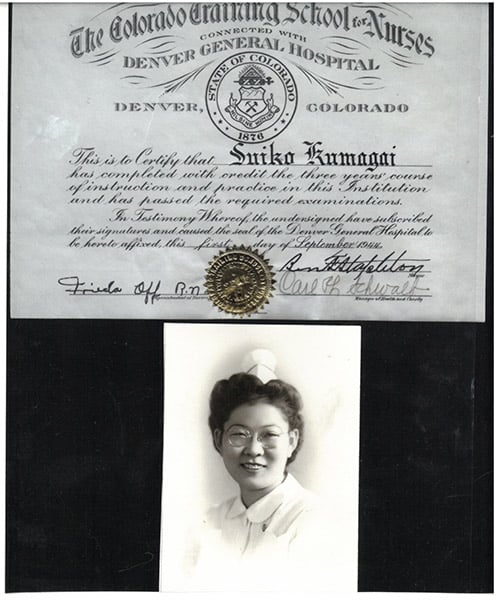

Suiko Kumagai and her Colorado Training School of Nurses |

Sue received her diploma from the Colorado Training School in May of 1944 and took her state boards for the registered nurse license. Then she heard that graduate nurses might be drafted, so she went to the Red Cross and enlisted in the Army Nurse Corps. After completing basic training at Fort Devons, Massachusetts, Sue, a new second lieutenant, was sent to Camp Edwards in Maine, which was the receiving area for war casualties. She volunteered for overseas duty, but her commanding officer wouldn’t release her. Sue served 13 months and when the war ended, the vast number of Army nurses were no longer needed. She was discharged but remained on the active reserve status. Sue is proud of a framed letter that President Harry Truman wrote which reads:

To you who answered the call of your country and served in its Armed Forces to bring about the total defeat of the enemy, I extend heartfelt thanks of a grateful nation.

She used her GI Bill to further her education in psychiatric nursing at the University of Colorado School of Nursing and received her bachelor’s degree. In 1950, she volunteered as a civilian to serve with the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC). The Field Agency was headquartered at Camp Kurihana, a former Japanese naval base near Hiroshima, Japan. The ABCC was established for the purpose of conducting long-range medical and biological research and investigating radiation effects on Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors.

Sue witnessed the devastating effects of radiation, including babies in utero at the time of the explosion; some born with microcephaly (smaller head circumference), mental retardation, and some without skin. Studies showed that mothers with heavy irradiation had decreased male offspring. Other effects in survivors included in increase an leukemia, cataracts, epilation (loss of hair), dental problems, premature again, and early death.

|

Both Sue’s nursing and linguistic skills were invaluable in setting up procedures for studies by the various clinics, translating basic medical procedures into Japanese, and working with the Hiroshima Red Cross Nursing staff in the training of nurses. Sue developed rapport with the Japanese staff and conducted monthly educational meetings. She also taught medical surgical nursing to Japanese nurses so they could better care for the atomic war victims. The Japanese nurses were amused at Sue’s dialect as her ancestors were peasant people from Northern Japan. Sue said that the speech of her people was not as refined as was the language of her students from metropolitan areas of Japan.

In 1952 the Korean War was on, and Sue was recalled to the States for active military status. She was deployed back to Japan where she cared for American GIs who had been prisoners of war in Korea. She assisted in organizing the Japan Army Nurse Corps as a part of the National Police Reserve (NPR) and trained the first Japanese Army nurse basic course. She bargained with the NPR for officer’s rank for the nurses. The NPR refused, and Sue said, “The best we could do for the enlisted Japanese nurses was to get them the rank of Sergeant First Class for staff nurses and for their chief nurse, the rank of Major.”

After the Korean conflict, Sue, wearing boots and fatigues, served as chief nurse in the Fourth Surgical Field Hospital in Stuttgart, Germany. But soon another war would send her back to the Pacific. During the Vietnam War she served as an assistant chief nurse in Saigon with a surgical hospital unit. In 1970 she returned to Colorado where she completed her military nurse career at Fitzsimons Army Hospital. In 1973, Sue had achieved the rank of Colonel and retired from the Army, counting 28 years of service to Uncle Sam. She shrugs when her medals, ribbons, and citations are mentioned. She keeps them in a box and says, “Others have the same ones. You pick them up.”