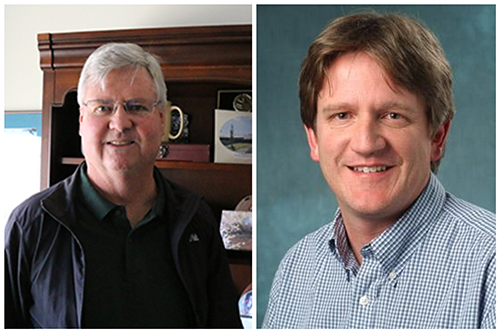

It wasn’t long after John Carpenter and Ted Randolph started working at the University of Colorado that a mutual friend and colleague suggested they collaborate.

Both were already experts in protein chemistry, and they were just a campus away from each other as Carpenter began working at the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Randolph started in at CU Boulder in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering.

During the course of their collaboration in the following decades, the duo transformed the biopharmaceutical industry.

More than two decades later, they were presented with a rare honor in pharmaceutical sciences: The January 2020 Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences issue was dedicated to Carpenter, PhD, and Randolph, PhD.

The dedication is a recognition of who the journal calls two “true giants” in pharmaceutical sciences.

Together, Carpenter and Randolph, who have been collaborators since 1993, have published more than 300 peer-reviewed papers and are inventors on 42 issued patents. They’ve educated scientists who are carrying on work in their highly specialized field of biopharmaceutical chemistry across the globe.

They are also the co-directors of the Center for Pharmaceutical Biotechnology.

“It was exciting,” Carpenter said. “It’s a really great honor to be recognized by my peers with my partner in crime, Ted Randolph.”

Randolph added: “It’s just great fun. What’s really nice is we got a pile of submissions from our very best friends and colleagues. It’s exciting to see the names of people you collaborated with, and a lot of past students who are publishing in the field.”

As a testament to their impact, a group of journal editors — mostly former students and colleagues — worked together to gather articles for the issue from scientists across the globe. A total of 92 papers were included in the special issue.

“This outpouring of interest and enthusiasm are clear demonstrations of the respect and the admiration that pharmaceutical and biological engineering scientists around the

world have for the research contributions of Professor Carpenter and Professor Randolph and their longstanding commitments to training graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and visiting scientists, and their desire and their ability to collaborate with scientists in the pharmaceutical sciences and biological engineering,” the journal’s editor-in-chief, Dr. Ronald T. Borchardt, wrote.

CU Pharmacy Dean Ralph Altiere said the issue represents a tremendous accomplishment and honor.

“It is a rare honor to have a scientific journal volume dedicated to individual researchers and both John and Ted are most deserving of this recognition,” he said. “This dedication also brings great honor to our school for which we are most grateful to John and Ted.”

Broadly, Carpenter and Randolph work in the field of pharmaceutical biotechnology, where, according to the journal, they have shared their expertise in proteins with the drug development industry, guided regulatory strategies, among many other accomplishments. When they started their work, it required on-the-job training — the kind of work that made Carpenter and Randolph pioneers in the industry.

Their partnership — and respective areas of expertise — have allowed the team to tackle problems from two different perspectives, and pass on lessons to each other's students.

“I’m an engineer and John came more from a scientist point of view,” Randolph said, adding that engineering students would often have to answer pharmaceutical sciences questions, and vice versa. “We realized right away that each of us had expertise gaps that the other was able to fill.”

A significant portion of their work has been centered on developing vaccines and helping improve drug products that most people recognize as household names.

Their work: When miracle drugs stop working

“If you ever watch the evening news, you see them advertised as Humira, insulins, a lot of injectables and protein products,” Carpenter said. “There are literally hundreds of them now. And so, pharmaceutical biotechnology is working on how those products are developed, how they are stabilized, how they degrade, how you analyze them, how you process them, like freeze-drying.”

For many patients, the drugs are essential to treat conditions such as arthritis and Crohn’s Disease, a chronic inflammatory bowel condition that can cause life-threatening bleeding. As Carpenter put it: “They’re miracle drugs.”

But for some patients, the drugs eventually stop working.

“The reason for that, a lot of times, is that the drug is acting like a vaccine in the body. The person literally has an immune response to the drug, and the drug is just cleared out by the body,” he said. “In a lot of cases, it’s because the protein has been clumped up into what are aggregates. They’re literally particles — you can actually see them, not with your eyeball, but with special instruments.”

To the body, those particles look like a virus or bacteria. So just like it would with a virus or bacteria, the body jumps into action to clear them out.

“The body is really attuned to looking for microbial or viral attacks,” Randolph said. “How does it recognize that it’s being attacked? The body looks for small particles, different from things it’s seen before, and viruses and bacteria are small particles coated with protein.”

But when it comes to miracle protein drugs that patients rely on, that reaction leads to questions: What causes this, and how do you stop it?

That’s where Carpenter and Randolph come in. As part of their decades of research, the duo has worked on answering the following questions: “what causes that, how do you control it, how do you properly analyze it, how do you get the Food and Drug Administration to pay attention to it?” Carpenter said.

They know proteins are sensitive.

“Since proteins are so sensitive, almost anything you do can cause particles, including how the pharmacist or the patient handles it at the end,” Carpenter said. “A lot of the ways they ship them cause mechanical stress and freeze thawing and that may cause particles.”

Part of the team’s most recent work involves working with a hospital to determine how pharmacy handling of the product affects product quality.

Getting to the bottom of issues like this is high-stakes work.

When miracle drugs stop working, the consequences can be debilitating for patients. It’s a reality Carpenter knows well. His niece, who lives with Crohn’s Disease, went through a cycle of successfully using a drug for a year or two — only for it to stop working. Eventually, she ran out of approved biologics, and went on high-dose prednisone, a treatment rife with side effects. About two years ago, a new biologic was approved, Carpenter said, and she’s been using it successfully since.

“It really affects patients dramatically,” Randolph said.

Because of Carpenter’s and Randolph’s work, the pharmaceutical industry is making changes, and implementing stronger analysis techniques for their products.

“Part of our goal is to keep pushing the industry to use the best analytical methods and not just to check the final product, but to monitor the product along the way,” Carpenter said. “And so, now, there's a lot more effort on making higher-quality products because of that kind of work.”

Work with vaccines

For the research duo, work with vaccines is the opposite side of the coin, but it’s just as important.

“In that particular case, we’re trying to create these immune responses,” Randolph said. “It turns out it’s almost as hard in both directions. We’re trying to get body to generate a protective response.”

This includes making sure formulations are irritating enough to the body so that it defends itself. Current work in this area includes developing a vaccine for Ebola that can be used in warmer climates. As of now, the vaccine for Ebola must be maintained at -60 degrees centigrade.

“In the jungle, it doesn’t work,” Randolph said.

But because of their advances, new formulations of the vaccine could be stable at 50 degrees centigrade.

“You can take these vaccines without any refrigeration in these countries,” he said, adding that the impact on patients is tremendous. “The science is motivating by itself. As you are working on these things, you better hurry up.”

Transition to retirement for Carpenter

With a clear impact in the field, Carpenter is beginning a gradual retirement. Randolph is continuing his work at CU Boulder.

As Carpenter transitions, he still plans to share his knowledge with the field. The team is often invited to give talks and work as consultants for pharmaceutical companies. He is also still a journal editor, and in his spare time, he likes to fish.

Randolph said it’s impressive to see the generation of students they taught continue to push the industry forward.

“More or less, the students who came to our groups had to face questions from both sides during every single exam, suffered being able to

answer engineering questions and vice versa,” Randolph said. “It made it a lot of work and their PhD theses much, much better. It’s why you see so many of

these students are leading industrial groups around the world. It’s really a validation to see those students being so successful.”

Carpenter’s and Randolph’s impact will remain significant for the industry.

“It’s interesting and motivating: a lot of the work that John and I have done is very close to patients,” Randolph said. “Some types of research, if it really succeeds, might appear in something that might help patients.”