Clinicians and researchers from ACCORDS at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus and Children’s Hospital Colorado have completed the first phase of a two-part study on the behavioral and mental health needs of children with severe chronic medical conditions.

Known as children with medical complexity (CMC), this population represents between 0.5 to 5% of the U.S. child health, but they represent about 30% of all health expenditures. There is a wide variety of medical conditions that CMC could potentially have to qualify. CMC can be children with neurological impairments such as cerebral palsy, developmental disorders or intractable epilepsy; they can have multisystemic genetic conditions; or have had an organ transplant. No two children are alike in their needs – one of the factors that make this patient group difficult to study.

Kristina Malik, MD, is a principal investigator on the project with the Children and Youth with Special Health Needs National Research Network, despite not having any officially funded research time. As a full-time complex care pediatrician at Children’s Hospital Colorado Special Care Clinic, Malik sees access to mental and behavioral health as a common theme among her patients. However, the mental and behavioral health needs of these children are as varied as the medical issues they live with.

Behavioral and mental health needs impacting clinical care

“For CMC who may be non-verbal, there is a concern that these children are unable to express pain or anxiety the same way a verbal child does. That child may need a mental and behavioral health provider who understands that concern,” Malik said. “A child's needs may stem from trauma from all their medical appointments over years. While they’ve received lifesaving medical treatments, it may be traumatic to them.”

Malik sees these concerns in her patients’ families. The difficulties they have accessing mental and behavioral healthcare is what inspired her to explore the best way to serve the population.

According to Malik, much of the research for CMC and their families explores the issue at a high systems level, focused on recommended changes to hospital care, insurance or state programs. “I've always been interested in the idea of care I can provide integrated into my clinic,” Malik said. “As a provider, I try to think about what I can do to make a difference for my patients. The more patients I see, the more I realize that providing my patients with the best care involves providers being involved in clinical research.”

In some complex care programs like Special Care Clinic, patients have integrated psychologists and psychiatrists on their care team. In her two-part project, Malik is exploring how prevalent this type of team is for all CMC.

Examining complex care programs

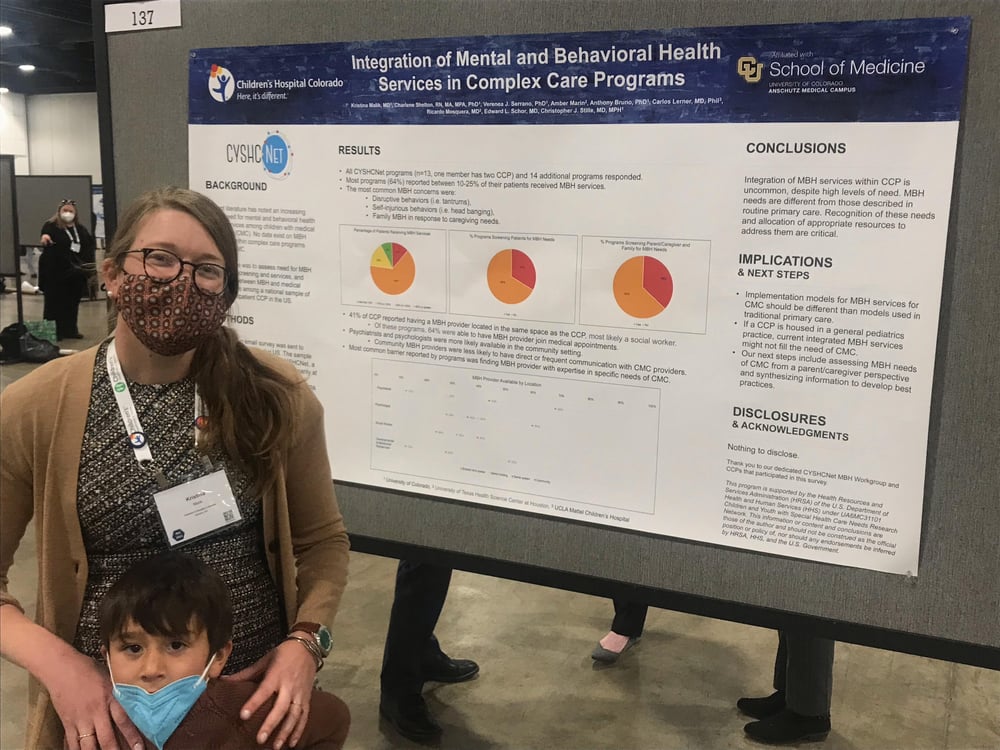

In the work recently presented at a national pediatric conference, Malik and the research team initially surveyed complex care programs (CCP) across the nation, with the majority in the research network, to understand how each CCP addresses the mental and behavioral health of its patients.

“We asked if they have a mental and behavioral health provider at the CCP, in the hospital system, and in the community. We also want to understand how useful the CPPs found these resources,” Malik said.

About 40% of the programs surveyed had a mental and behavioral health provider located in their clinic. However, this individual was often a social worker. According to Malik, that is a valuable resource to have, but social workers have many tasks aside from solely addressing mental and behavioral health. Depending on their scope of practice, what they are able to provide can be variable. The researchers found that psychiatrists and psychologists are more available in the community setting but were less likely to have direct contact with the CCPs.

An unstudied need

“Even though families were receiving care in the community, the need for medical behavioral health integration might not be achieved. For many CMC, their medical needs might be affected or influenced by mental and behavioral health needs, and they aren’t receiving that care. It wasn't a surprise, but it was really helpful to understand that integration of mental and behavioral health was pretty uncommon, despite the fact that there was a highly reported need,” Malik said.

Not only did Malik and her team find a high level of need for this care for CMCs, but they discovered that CMCs’ needs for mental and behavioral health care were unique and different from the general population.

“It wasn't unexpected, but at the same time, this is the first time anyone has ever asked these questions and really put numbers to this great need that is not really being addressed,” Malik said. “We know in the current state of health that mental behavioral health is a priority. And we know that children with medical complexity are a huge health system user, but no one has brought these two worlds together.”

The team has moved into the second phase of their project where they are interviewing caregivers of CMC on their experience with mental and behavioral health services for their children.

“We started this project before the pandemic, but we are asking questions about the pandemic because we know that the need for mental and behavioral health supports for children has increased during the pandemic. We've learned so much about providing mental and behavioral health for children in general, and how patients, families and healthcare systems are willing to address it.”