What happens to patients when they’re transferred from one hospital to another has not been well studied, and national guidelines to standardize transfer procedures are lacking, says a University of Colorado Department of Medicine faculty member and hospitalist. But what is known about inter-hospital transfers is troubling enough: Patients moved between acute-care hospitals often experience worse clinical outcomes and higher costs than other patients with similar conditions.

That’s the premise behind a research project that has been selected for the Society of General Internal Medicine's 2024 Founders’ Grant, announced May 18 at SGIM's annual meeting in Boston.

Amy Yu, MD, an assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine, calls herself an “inter-hospital transfer change agent.” She has previously gathered data from physicians, advanced practice providers, and nurses as she seeks to find ways to improve patient safety and outcomes during and after inter-hospital transfer.

Now she plans to combine that data with perspectives from patients who have been through transfers and the care partners who assist them. “That’s the population that I’ve really wanted to talk to,” she says. “At the end of the day, my research is really about patients and their loved ones. They’re the end-users of everything we do.”

Amy Yu, MD, receives the Society of General Internal Medicine 2024 Founders’ Grant at SGIM's annual meeting in Boston on May 18, 2024. Photo provided by Amy Yu.

Amy Yu, MD, receives the Society of General Internal Medicine 2024 Founders’ Grant at SGIM's annual meeting in Boston on May 18, 2024. Photo provided by Amy Yu.

A strong record

In addition to providing $10,000 toward Yu’s latest research, the Founders’ Grant “was created to provide support to junior investigators who exhibit significant potential for a successful research career and who need to establish a strong research funding base,” SGIM says.

A letter to Yu quotes the grant selection committee as saying: “This is a well-written proposal tackling an important (and common) issue. Dr. Yu has a strong record. This is a highly significant and innovative project that will address an important gap in patient care.”

“This is such a critical piece for my research trajectory,” Yu says. “It’s a launching pad, in a way.”

Often, patients are transferred between hospitals when they need specialized treatment or advanced care not available at the originating hospital. The UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital on the CU Anschutz campus is frequently the destination for patient transfers.

Yu says that, in the absence of standardized guidelines, hospitals often must create their own transfer protocols that differ from one facility to the next. That can lead to inconsistencies in care coordination – fragmented communication, incomplete transfer of vital patient information, and potential patient harm and poor outcomes.

A troubling experience

Yu talks of a troubling experience she had as a second-year resident that galvanized her interest in this line of research.

She remembers a call from a hospital admissions staffer who said, “Hey, your new admission is here. This is the nurse’s number. Can you call her back? She’s stressed out because the patient has been here for a couple of hours.”

The patient – a woman who Yu calls Norma, not her real name – had been transferred from a small rural hospital. Yu reached the nurse, who said Norma was in pain and hungry and wanted to know what the plan was.

“I opened up the chart and there was no documentation about why Norma was here or her medical problems. I asked the nurse if papers came with Norma from the other hospital. She said, no. I think, great, I’m going to be flying blind.”

Yu went to meet Norma and her husband. “You can imagine my embarrassment when I go into the room several hours after they arrived and say, ‘Hi, I’m Dr. Yu, I'm going to take care of you,” and her husband jumps up from his chair and says, ‘Where have you been? Why haven’t you done anything?’ And Norma was on the bed, in a fetal position, just crying. It felt so awful because I didn’t know why she was here. I had to ask them.”

For Yu – who as a little girl used the run around the house carrying a little Johnson & Johnson first aid kit, trying to “cure” her family – the experience was hard to take. “I was a little teary about it because I went into medicine to help people. I felt I could not take care of Norma the way she deserved to be cared for, and it was clear they felt that, too.”

"My goal is to think about how we can better design systems that work for the people involved so that patients, their care partners, and clinicians can experience the type of transfers that put people first," says Amy Yu, MD. Photo provided by Amy Yu.

Understanding key barriers

A 2019 national study of 53,00 inter-hospital transfers of patients on Medicare across 15 disease categories found that transfers were associated with higher costs, longer hospital stays, and, for some disease categories, with higher 30-day mortality rates when compared to a similar number of comparable patients who weren’t transferred, although death rates were lower for other diseases.

Yu’s goal is to better understand key barriers to patient-centered care coordination during inter-hospital transfers – barriers such as faulty communication and missing information. She plans to ask 15 patient and caregiver pairs similar questions to those she asked doctors and nurses. She’ll then correlate those results with her earlier findings to inform future research proposals.

“I want to talk to people like Norma and her husband – what they thought coming to the hospital would be like, what they expected from their providers, and what we could be doing better on communication to make sure that inter-hospital transfers are safer and more effective.”

Yu is just one of several Division of Hospital Medicine faculty who have been looking under the hood of hospital operations in their research in hopes of making things better for patients and the people who work there.

“These kinds of transfers can create situations where it’s a no-win for everyone. When they go well, they’re great for everyone, but when they don’t, they’re stressful and feel unsafe. My goal is to think about how we can better design systems that work for the people involved so that patients, their care partners, and clinicians can experience the type of transfers that put people first.”

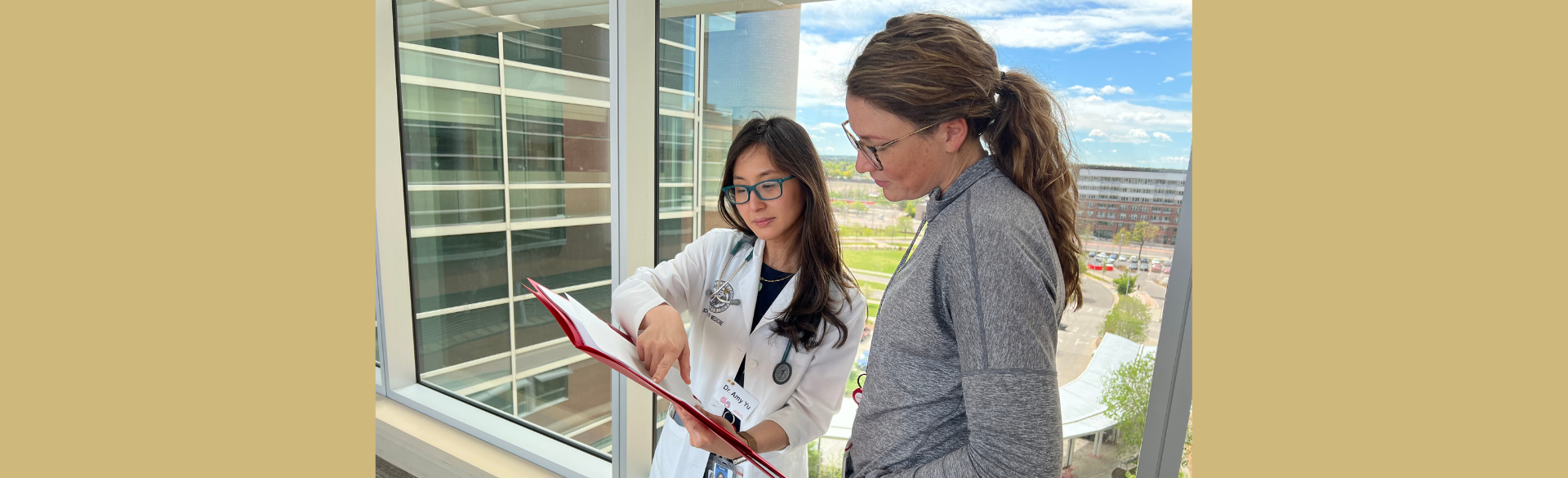

Photo at top: Amy Yu, MD, (left) with advanced practice provider Erin Szemak, DNP, APRN. Photo provided by Amy Yu.