It happened so fast, and it was so unexpected.

In August 2020, Mario Carrasco got what he suspected was COVID-19 and took Tylenol to combat his high fever. When that didn’t work, he took an antibiotic he had received from Mexico and eventually felt better. For several months afterward, he felt fine. He felt like he always does.

But then his stomach started hurting. He felt nauseous and couldn’t keep food down. He turned yellow. During a visit to Montrose Memorial Hospital in Montrose, Colorado, physicians informed him that his liver enzymes were high, indicating inflammation. And he quickly got worse, to the point that on April 28, 2021, he was flown to UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora.

Over more than a week, the terrifying downward spiral continued as his liver failed and his family scrambled for options since he had entered the hospital uninsured and couldn’t get on the transplant recipient list without insurance. However, with a lot of work and support from a multidisciplinary care team, he got insurance through a significantly expedited process and then onto the liver transplant list very soon after.

Less than an hour after getting onto the transplant list, he was being prepped for surgery. A compatible donor liver was on its way.

“The likelihood of getting a transplant the same day you’re put on the list is extremely rare, almost unheard of,” says Elizabeth Pomfret, MD, PhD, chief of transplant surgery in the University of Colorado Department of Surgery. “What makes Mario’s experience so rare is the fact that we were able to get not only his insurance fast-tracked, but his approval for the transplant list, which usually takes many days to do.”

Feeling well, then a quick decline

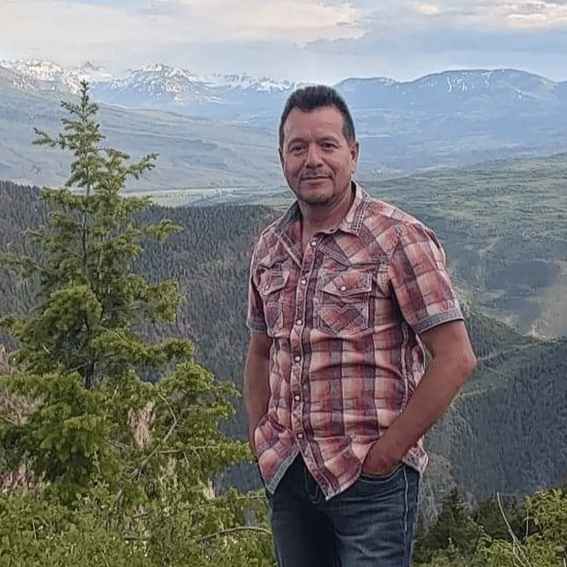

For most of his life, Carrasco, 54, has enjoyed good health. Since coming to the United States from Chihuahua, Mexico, in 1992 and settling with his family in Delta, Colorado, he built a career in construction – working hard and then coming home to his wife, Maria, and children, Carlos, Ivan, and Jennifer, all now adults.

Mario Carrasco enjoys spending time with his family in the mountains near his Delta, Colorado, home.

He figured he would be fine after rebounding from what he thought was COVID-19 in August 2020. But then he started feeling poorly and things just kept getting worse. A blood draw indicated his liver enzymes were elevated, and by the time his wife and daughter took him to Montrose Memorial Hospital, they were even higher.

“They told us he had the option of going to Grand Junction or Denver, but the liver specialist was in Denver, so they flew him out to Denver,” explains Jennifer Carrasco. “Even then, he didn’t think it was anything serious.”

Carrasco was in the hospital for less than two weeks “when everything started to go down,” he recalls. He had an internal normalized ratio (INR) test, which shows how quickly the blood clots, indicating how well the liver is working by producing enough proteins. A normal INR is 1.0; Carrasco’s was 4.0, an alarming number indicating extremely slow blood clotting and poor liver function.

Perhaps even worse, during this time his father-in-law died, so his health worries were compounded by grief. And then he had a seizure.

"We had talked with him the night he had the seizure and he seemed fine,” recalls Carlos Carrasco. “But then he was unconscious for almost two weeks, they call it a hepatic encephalopathy coma.” Hepatic encephalopathy happens when a damaged liver is unable to remove toxins from the blood, which can impact brain function.

Trying for a transplant

“My mom was the one who asked if his liver could be salvaged, but they said it was pretty bad and more than likely he was going to need a transplant,” Jennifer Carrasco says. “The damage was too advanced.”

Maria and Mario Carrasco

However, Carrasco at first couldn’t be added to the liver transplant registry because he lacked medical insurance. Carlos and Jennifer Carrasco started a GoFundMe campaign that ultimately raised more than $18,000, “but we researched it and it said that transplants can cost $250,000 to $500,000, something like that, plus after a transplant you need insurance for anti-rejection medicine the rest of your life, which is really expensive, and follow-up checkups,” Carlos Carrasco says. “Some of our family members were going to see if they could borrow whatever it would cost, but it was just too much money. Our hopes were low, and then they said they were going to put him in hospice.”

This is the point, though, when Pomfret, who is chief of transplant surgery at UCHealth, thought about a lecture that Monica Grafals, MD, an associate professor of clinical practice in the CU School of Medicine and kidney transplant specialist with UCHealth, gave to the CU transplant surgery team about the Hispanic Transplant Clinic.

Grafals and her Spanish-speaking colleagues, with support from Pomfret and the Division of Transplant Surgery, started the clinic in October 2018 in response to significant need in traditionally underrepresented Hispanic communities. Between October 2018 and October 2021, clinic faculty saw a 300% increase in Hispanic patients accessing clinic services.

“When Dr. Grafals came and spoke to the transplant team, she was focusing on kidney patients, but I was thinking this would be applicable for patients with liver failure,” Pomfret says. “That’s when the head of transplant hepatology said, ‘We’ve got a guy who’s been sitting in the hospital here for the past two weeks, he has acute liver failure but he seems fine from all other perspectives.’”

“Like hitting the lottery”

Pomfret credits a multidisciplinary approach to patient care for the next steps in Carrasco’s journey. She asked Grafals whether Carrasco could enroll in the Denver Health Medical Plan’s Elevate Exchange, a local, nonprofit health insurance company that is part of the Colorado health insurance marketplace. “This is why integrated, multidisciplinary programs are so vital for the best patient care,” Pomfret says.

Working closely with Grafals and other team members from the Hispanic Transplant Clinic, Carrasco’s family dove into the paperwork with a fervor fueled by the seriousness of his situation. Grafals went so far as to contact state legislators to ask whether there was any reason his insurance application couldn’t be expedited.

"He's a wonderful man with a very special and loving family," Grafals says. "We wanted to do absolutely everything we could do help him because his situation was desperate. He was in acute liver failure."

The definition of acute liver failure "is you have a 90% chance of death very soon, sometimes within days,” Pomfret explains. “That’s where he was at. I never thought we’d get a deceased liver in time, so we were looking into whether there was somebody from the family who could donate.”

But thanks to expedited paperwork, Carrasco was able to access Elevate Exchange coverage and get onto the liver transplant recipient list. Within 45 minutes of getting on the list, as Carlos Carrasco was filling out some final paperwork, “I heard about this liver,” Pomfret says.

It was a deceased donor liver, and it was already in Denver but the initial intended recipient either wasn’t healthy enough for transplant or had died before receiving it. And it was a match for Carrasco.

“It was like hitting the lottery,” Pomfret says. “It’s a case of one in a billion odds, the stars aligning and everything falling into place: the fact that the insurance was fast-tracked when often that process can take weeks, the expedited process for getting him onto the transplant list, and then how fast he matched with a donor liver. He was almost out of time when I got the call about this liver. I said, ‘Great, we’ll take it’ and within an hour of him getting on the list, we were heading into surgery.”

Back to normal life and feeling grateful

Carrasco’s recovery was occasionally painful, and he spent the month following his surgery at a family friend’s Denver apartment, but “he’s been an absolutely wonderful patient,” Pomfret says. “He’s very aware of the significance of this donation.”

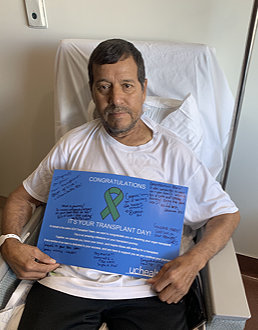

Mario Carrasco received support from a multidisciplinary care team.

Clinicians trace Carrasco’s acute liver failure to the antibiotics he took, which is an unusual outcome, Pomfret says, “but happens a few times a year, and it’s not because the antibiotics he took were from Mexico. It happens with FDA-approved antibiotics, too.”

While Carrasco has made changes to his diet – limiting foods that don’t react well with his medications – and has blood work performed every two weeks, he’s returned to normal for the most part. He’s back at work in construction, back to playing basketball in the evenings, and “feeling grateful to God and to my family,” he says.

When he was so sick in the hospital, family members who were unable to enter due to COVID-19 restrictions waited in a hospital courtyard, sometimes as many as 20 people who love him.

“I’m very thankful for that,” he says. “This whole experience has made me so grateful for all the doctors, all the staff in the hospital, who supported me and my family.”

.png)