At the first sign of morning light on October 1, dozens of adults and children stood huddled together on the grassy Parade Grounds of University of Colorado Anschutz, some shivering in the pre-dawn cold, some chattering nervously or taking selfies. Several had what looked like bloody limbs; others had burned faces. One seemed to be missing a hand.

These people had just come from an auditorium lobby at nearby UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), where moulage artists had slathered them with fake blood and special-effects makeup.

This was no pre-Halloween party. These were actors with important roles to play in an elaborate simulation. This half-day exercise was designed to provide hospital emergency department personnel as well as first responders, campus emergency teams, and others an opportunity to practice responding to a mass-casualty disaster under conditions approximating the real thing.

Among the actors were Shannon Werner and Sophie Mason, who played injured sisters. Werner is a first-year student at the CU Anschutz College of Nursing who learned about the drill in one of her labs and wanted to help out, and Mason is a Colorado actor and model.

“This is a bit like improv,” said Mason, who sported a bloody gash across her face. “You’re given things to do on the spot, and you can’t really do a bunch of preparation.”

Photo at top: A manikin representing a deceased victim lies on the Parade Grounds of CU Anschutz near a UCHealth helicopter used in the drill. Photo by Melissa Santorelli.

Photo at left: Drill actors Shannon Werner and Sophie Mason on the Parade Grounds of CU Anschutz. Center: Actors display their "injuries." Right: Actors await the beginning of the drill at the moulage center at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital. Photos by Melissa Santorelli and Mark Harden.

‘Truly exciting’

The exercise directors for the UCH emergency department (ED) were Jessica Ryder, MD, an assistant professor in the CU Anschutz School of Medicine’s Department of Emergency Medicine and an emergency physician at UCH, and Natasha Vandeford, a charge nurse at UCH and coordinator for disaster preparedness in the hospital’s ED. They and many others have been planning the exercise since March.

This is the second time that Ryder has helped lead a live disaster-preparedness drill like this at CU Anschutz. This exercise was by far the biggest, with roughly 420 people involved as “players,” and with more than just hospital personnel involved this time.

“Last year, we didn’t have the pre-hospital aspect with police and fire and EMS crews,” Ryder says. “We just staged the patients in the ambulance bay and timed them coming into the ED. This year, having the ability to practice everything, from the [on scene] disaster response to hospital admission, is truly exciting.”

For the ED, there were two main goals to the exercise, Ryder says: “One is practicing our disaster-response protocols and procedures that we've been training on and improving over the last year or two. The other is to identify any gaps in those systems so that we can improve them in the coming years.”

The drill, she says, provided an opportunity for ED providers, trainees, and staff “to manage a surge of patients in a high-stress environment that’s also a psychologically safe and no-fail environment for them. We’re testing procedures, not individuals.”

Photos: As the drill begins, actors and emergency crews interact on the Parade Grounds. Photos by Tori Flarity and Melissa Santorelli.

A chilling scenario

The exercise simulated a chilling scenario: A helicopter landing at the UCH helipad was hit by lightning, careened into a building, then crashed onto the Parade Grounds, where people were setting up for a campus fall festival. About 100 people were injured or killed. (For the exercise, a real UCHealth helicopter landed at the site.)

The drill unfolded at three main “scenes,” or locations. Scene One was at the Parade Grounds, where dozens of actors portraying injured victims were sprawled out on the lawn, some of them moaning and calling for help. Their injuries varied greatly in severity and complexity.

Among the actors were young students of Tiffeny O’Dell, a science teacher at Byers Junior-Senior High School, in rural eastern Colorado. She teaches classes that offer certified nursing assistant, phlebotomy, and emergency medical technician certification.

“I try to introduce them to all aspects of health care, and I have some kiddos who are very interested in moving on with that,” she said, adding that some may want to come to CU Anschutz for medical school someday.

Organic triage

As the drill began at 7:30 a.m., the CU Anschutz Police Department responded first, and campus dispatchers contacted Aurora police, Aurora Fire Rescue, the nearby Strasburg/Byers Fire Protection District, and Falck Ambulance Service, which serves Aurora. About six fire trucks, 10 ambulances, and 10 command vehicles responded to the Parade Grounds. CU Anschutz also activated its emergency response and crisis communications teams.

Soon, emergency medical services (EMS) personnel fanned out across the Parade Grounds to engage with “victims” and perform triage. “The EMS people were told to organically triage patients as they see fit and bring in the ones to the ED that they think should be managed first,” Ryder says.

The Parade Grounds emergency-operations segment of the drill was managed by Garrey Martinez, director of emergency management at CU Anschutz, and Rachel Cruz, the campus emergency management program manager. For their team, the exercise was a stress test for the campus’ Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan outlining how to respond to disasters.

“The way that it would happen in real life is the way that we built the scenario,” Martinez says. “Once everyone arrived at the scene, they established a unified command to ensure that all entities were collaborating with one voice, one tempo.”

Part of the scenario was the possibility that the chopper crash could have been the result of an act of terrorism, Martinez says. “So we set out to secure the scene and also identify all of the victims to make sure we understand who they are and what their affiliation is on campus.”

Another task was to coordinate communications on the incident to the campus, to news media, and the world at large, both to convey information and to keep the campus safe, he says.

As for conducting the exercise, Martinez says his team included “site safety” personnel and a nurse on the Parade Grounds to ensure participants were safe and not “experiencing a mental health crisis because of the chaos. This exercise happened on the anniversary of the Las Vegas mass shooting. People now have a variety of lived experiences that could trigger in unexpected ways, and safety is our top priority.”

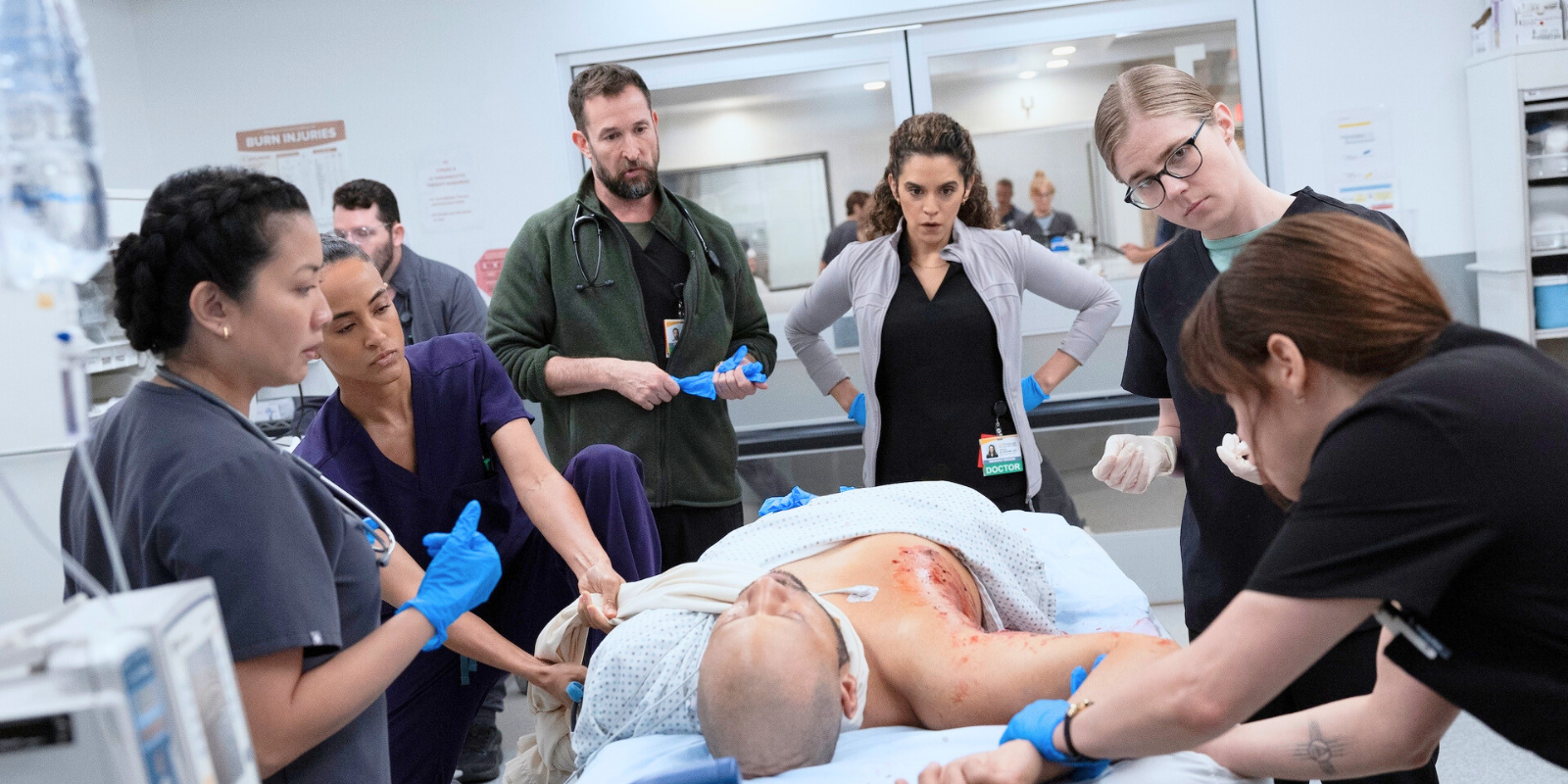

Photos: "Patients" are treated in the hospital emergency department. Photos by Melissa Santorelli.

The ED springs into action

Those who couldn’t be treated at the scene were transported to the UCH ED a few blocks away. The ED was Scene Two in the drill.

Once the ED was notified of a large event involving many casualties, it set up its own triage operation in the ambulance bay at one of the ED’s entrances, with teams wearing color-coded vests to indicate their role. In addition to ED medical technicians triaging arriving exercise patients, a group of observing CU medical students with computers were testing artificial-intelligence triage models as a side project while the “patients” arrived.

Inside the ED, personnel prepared to care for trauma and burn patients, color-coded green, yellow, or red based on the severity of their injuries. One by one, actor patients were wheeled in on gurneys or in wheelchairs and were dispatched to one of the ED’s dozens of exam rooms for care appropriate to their injuries. Other actors walked in by themselves to simulate ambulatory patients.

Drill patients were assigned to present a wide variety of injury scenarios, including a severely injured woman who was pregnant. Care teams were provided with detailed data on each patient, from vital signs to allergies to breathing and cardiac patterns, and were tasked with making real-time care decisions.

The ED teams performed a host of simulated medical interventions, sometimes using manikins and task trainers – artificial replicas of body parts – including intubations and cricothyrotomies (surgical airway placement), applying pelvic binders, and placing central venous catheters for patients needing rapid blood or fluid resuscitation.

Photos: Actor Cameron White wears a protective "cut suit" designed to allow medical teams to perform invasive procedures without injuring him. Photos by Melissa Santorelli.

A cut suit plays a starring role

Cameron White – Ryder’s husband – had a starring role in the drill. He wore a surgical “cut suit,” a protective spongy outer garment designed to allow first responders and physicians to safely perform various real procedures on a live actor. His face and jaw were mangled, part of his right arm was torn away, he was coughing up blood, and a bolt was embedded in his left chest.

All this was happening while the ED was receiving and treating actual patients. While the ED’s regular working staff took care of the real patients, a separate exercise staff – supplemented by third- and fourth-year Denver Health Residency in Emergency Medicine physicians – managed care of the actor patients. Ryder and Vandeford took extra precautions during the planning process to ensure real patient care was prioritized and minimally impacted during the exercise.

Many of the ED’s hospital partner core teams “played” in the drill, from trauma, burn, orthopedics, labor and delivery, and interventional radiology to imaging, pharmacy, blood bank, lab, and inpatient registration teams, Ryder says.

Scene Three took place in UCH's inpatient areas, where bed-board managers and inpatient units virtually practiced dealing with a surge, finding rooms for patients, and assigning care teams.

‘Incredibly successful’

While patient care was being provided, in a pair of UCH conference rooms, representatives of the hospital’s spiritual care and care management teams, along with the state’s volunteer Medical Reserve Corps, worked with actors portraying family and friends of the “victims,” reunifying them with their loved ones.

Following the drill, stakeholders will meet to assess how it went and what procedures can be improved upon.

“We never go into an exercise like this assuming that everything’s going to be perfect,” Martinez says. If it’s perfect, we didn’t design the exercise correctly. But overall, I’d say it was incredibly successful.”

Ryder repeatedly emphasized how valuable it was to have so many teams in and out of the hospital working together on staging such an elaborate exercise. “We really had lots of great partners on this,” she says.