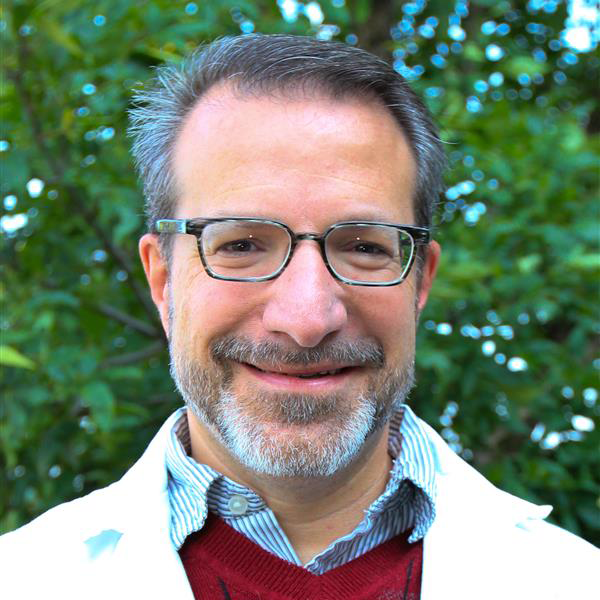

Jason Persoff, MD, listens to storms in much the same way he listens to patients: unhurriedly, questioningly, observing details that indicate background and environmental elements influencing and shaping the present moment.

And just as his patients have anatomy and physiology that factor into his treatment decisions, storms also have a body and a structure that inform everything from how he sets his camera and where he aims it, to how long he stands on his porch with a black wool sock extended into a storm, catching snowflakes.

“My neighbors might think it’s a little weird,” Persoff admits.

Persoff, an associate professor of hospital medicine in the University of Colorado School of Medicine, is a nationally and internationally recognized storm chaser of more than two decades who has carved a unique niche at the nexus of his passions for extreme meteorology and photography.

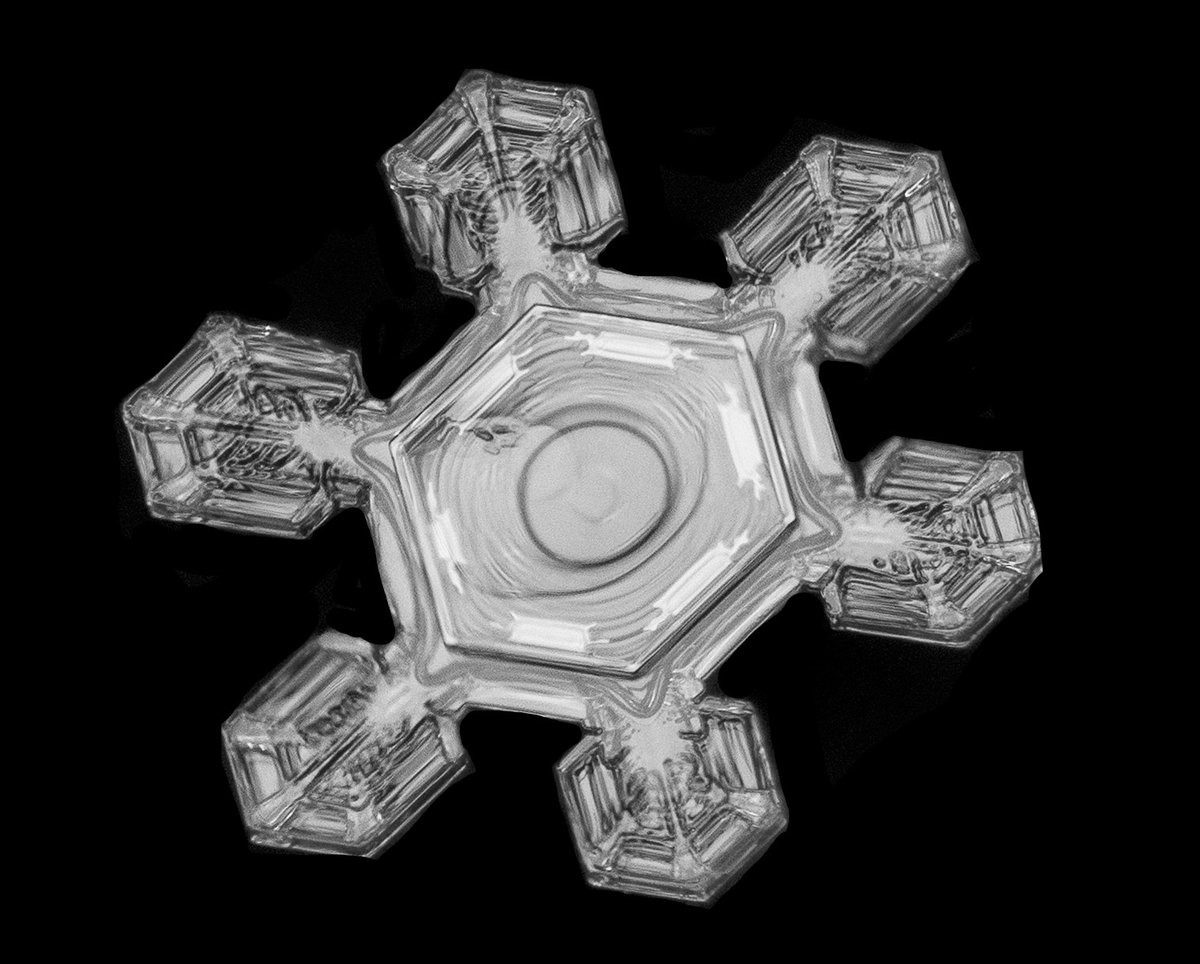

He is particularly known for his extraordinary macro photographs of snowflakes that define the fascinating detail and fleeting beauty of individual flakes. A display of his photography titled “Every One Is Unique: Photographs by Jason Persoff, MD” will be open January 31 to March 23 in the Fulginiti Pavilion Art Gallery on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus.

“One of the most important things about my photography is it gets people to pause and consider,” Persoff explains. “When I’m holding my camera, it’s like a warm sweater on a cold day, it’s just comfortable. It also keeps me mindful and grounded in the moment. Photography allows me to have and then to share the most incredible experiences.”

Capturing weather as a feeling

For as long as he can remember, Persoff has been mesmerized by storms. Growing up in Aurora, he was fascinated by the tornadoes that sometimes touched down there. He recalls watching “Night of the Twisters,” a documentary about deadly F5 tornados that touched down in Xenia, Ohio, in April 1974, in probably second grade “and I was hooked,” he recalls. “I always wanted to experience them and I got excited when the sirens went off.”

Around the same time, he was cultivating a growing interest in photography, so his parents gave him a Polaroid camera for his eighth birthday.

“I loved taking photos and I loved that Polaroid, but you’d get 10 shots and that’s that,” he says. “And usually at least one of them would be totally screwed up. My dad had an SLR Pentax that he let me borrow one day, so I took a bunch of pictures and he was pretty impressed with the quality.”

Persoff’s dad encouraged him to save for his own SLR, which he did and bought his own Pentax in fifth grade. In the spring of that year, a series of thunderstorms surged across Aurora “and I remember trying to frame the clouds to capture the feeling of these incredible storms,” he says. “I can remember consciously thinking about that, and it sort of began my journey to frame the sky as a feeling or an emotion, as an experience.”

Loving winter again

Eating breakfast one day as an undergraduate, Persoff read a story in USA Today about two storm chasers and the proverbial lightning struck. “Up until then, I’d never considered the possibility that you don’t have to stay static, that you can move with the weather,” Persoff says.

Not long after, he met his wife and they began storm chasing while he was in medical school, Persoff learning through trial and error how to shoot cloud formations and infant tornadoes and forks of lightning.

“I could go through six rolls of film and have no lightning bolt,” he remembers with a laugh. “Or, if I did have one it would be out of focus. Fortunately, there were these one-hour photo places where you only had to pay for the photos you kept, so I always sought those out.”

After moving to Florida for his residency and his first few years on staff at a hospital, Persoff and his family returned to Colorado, where he found that he did not enjoy the snow.

“It was fun as a kid, but by the time I got to medical school it sucked so bad because I had to drive to different hospitals and I learned to actually hate the winter,” he says. “When we came back to Colorado, I knew I had to find something that would help me enjoy wintertime.”

Perusing the internet one day, he came across a photo of a snowflake taken by Canadian photographer Don Komarechka. That cannot be a real snowflake, Persoff remembers thinking, but it was. He reached out to Komarechka, who began giving Persoff pointers, and bought Komarechka’s book “Sky Crystals: Unraveling the Mysteries of Snowflakes.”

“So, I tried photographing a few snowflakes,” he says, “and now I absolutely love wintertime.”

Seeing every detail

Geography plays a significant role in Persoff’s love for winter. Northern Colorado has the right combination of temperature, altitude, and humidity for stellar dendrites, a somewhat rare type of snowflake with six branches and fern-like crystal structures emanating from them.

“Most snow is not beautiful,” Persoff says. “You may get a lot of little pellets but not actual flakes, so we’re really lucky here and up north into the Canadian Rockies that we get stellar dendrites.”

Armed with tips from Komarechka, as well as his own knowledge of photography and weather, Persoff embarked on a journey of learning more with each storm. He learned that extending a black wool sock into the falling snow can help him catch individual flakes, which he photographs with a ring light, sets of extension tubes on his lens, and boundless patience.

Not every storm yields a snowflake image worth keeping, he has learned, and releasing the shutter is usually the first in a multi-step process. Some of his most intricate and detailed final photographs are the result of as many as 40 images layered on top of each other during the photo editing process.

Persoff also detailed his snowflake photography process in a series of YouTube videos that cover topics like how to light snowflakes, the equipment to use, and how to do it all on a budget.

“I think about Don Komarechka, who was so kind to teach me, and I feel like I want to pay it forward,” Persoff says. “It’s not for me to have a copyright on what snow looks like. I want people to stop and enjoy this. So often, we only deal with the consequences of it, and we’re getting ticked off by the ice on the road and the inconvenience. But when you consider the trillions of these flakes falling, and each one unique and so beautiful and transient.

“Much as I’ll spend time listening to a patient’s story, when I’m in the moment photographing a snowflake, I’m taking the time to see every detail, and it’s really opened up my world. It allows me to be present, to be only in that moment, and to really see.”