The very near future begins with a stark observation: “It was getting hotter.”

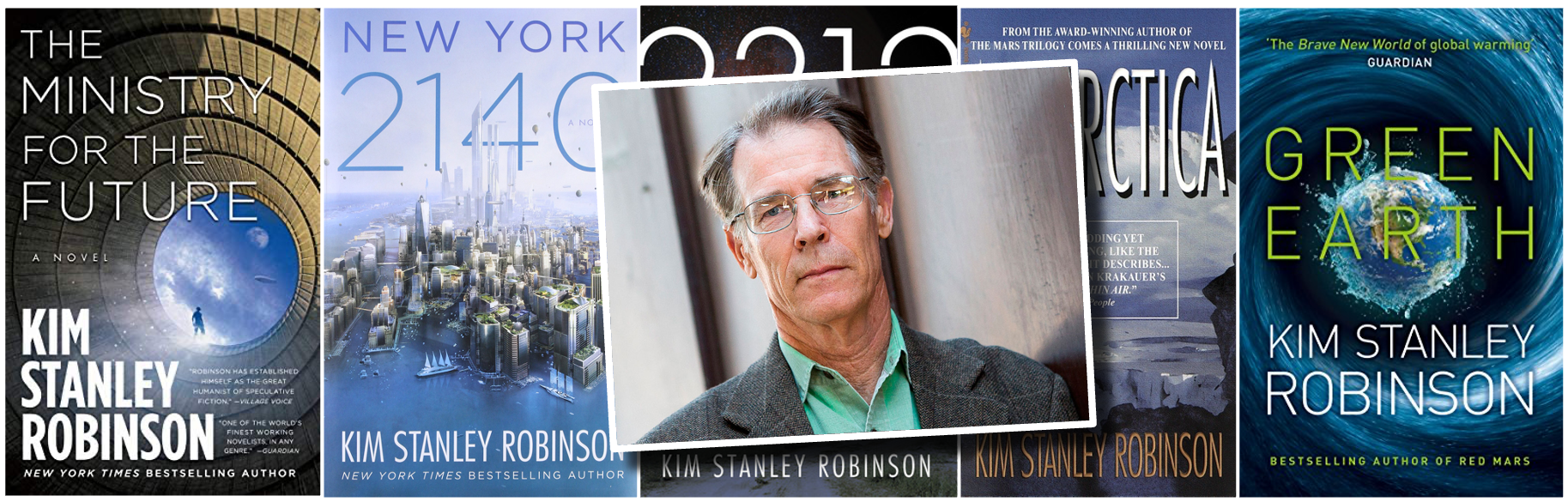

It’s a fictionalized future, one envisioned by Hugo- and Nebula-winning author Kim Stanley Robinson, PhD. But what follows in his 2020 novel, “The Ministry for the Future,” is a heat wave so intense that tens of millions die and a global race begins to course-correct the multiple and intersecting crises of climate change.

Robinson discussed these points of overlap between fiction and reality during a Grand Rounds question-and-answer session Friday hosted by the University of Colorado School of Medicine Climate & Health Program.

As one of literature’s most respected current science fiction writers, Robinson has often addressed themes of climate change that envision near- and not-too-distant future ramifications and ripple effects. In “The Ministry for the Future,” he presents multiple perspectives on climate crises barely 30 years in the future – from a former diplomat racing to convince bankers of how climate change can destabilize markets and currency to engineers proposing dyeing the Arctic Ocean yellow to stop it from absorbing sunlight and millions protesting in streets worldwide.

“We’re in history,” Robinson said. “It’s happening; we’re in climate change already. If you were to do near-future science fiction that didn’t take on climate change, you’d be missing the point of what we’re dealing with.”

Writing science fiction based on reality

Jay Lemery, MD, co-director of the CU Climate & Health Program and professor of emergency medicine in the CU School of Medicine, hosted the question-and-answer discussion and noted that he and other faculty members have used the first chapter of “The Ministry for the Future” in the classroom. In it, Robinson vividly describes a heat wave in India so catastrophic that millions die, including those seeking relief in a lake where the water was boiling hot.

Even though the scenario is fiction, Robinson said, in a way it was easy to envision a scenario in which power grids go out and people begin dying within 24 hours, in light of actual heat waves within the past 20 or 30 years that led to significant casualties.

“That part was easy,” he said. “Everybody can imagine it. It’s a matter of can you get the sentences on the page that smack you in the face.”

He noted that medical school faculty are in a unique position to communicate about climate change because “people will express all kinds of ideological positions until they’re sick and scared for their lives, and then they run to a science. The doctor becomes someone you’ll listen to, and that in our culture is very valuable.”

Making the realities of climate change tangible for medical students, he said, could involve asking students to hold their breaths for two minutes or conducting lessons in a sauna – experiences that would illustrate the extremes of what human beings could experience on Earth and how interpenetrated each person is with the planet.

“The biosphere is our body,” Robinson said. “You could say to (students), ‘Fifty percent of the DNA in your body is not human DNA – you are a swamp, you are a biome, you are a combination of creatures living together in a collaborative system of mutual aid.’”

Finding hope in the face of hopelessness

Lemery observed that it’s easy to feel hopeless when confronted with what seem like insurmountable climate catastrophes, and he wondered about the realistically hopeful note on which “The Ministry for the Future” ends.

“If we dodge a mass extinction event, that’s a utopian victory,” Robinson said, adding that hope is a function of existence on Earth. “Bacteria have hope, hunger is a hope – ‘gee, I hope I get food.’ When you are alive, you’re hoping, you’re hoping for the next breath, at the cellular level we’re hoping.”

Hope is easily crushed but it’s very stubborn, he said, and persistent over the long haul because it’s a function of being alive.

“The notion is this: You’re a brick in a wall, and it’s a big wall and you’re a little brick,” Robinson said. “But you’re part of a larger project than yourself. There’s mutual aid, there’s solidarity. And as for these big institutions that feel like they’re life-threatening and only out for themselves, they’re starting to think that if the Earth is destroyed it’s bad for business. So, each one of us, you put your shoulders to the wheel, and you don’t have to invent the wheel, nor do you have to make the wheel, but it’s a big wheel and you push and you’re part of a bigger group that’s pushing also.”