Some of the most profound insights into finding hope amid an advanced cancer diagnosis came at 1 a.m. in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) for Robert Bennett, PhD, a post-doctoral fellow in palliative care and aging research in the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Working late as a PICU nurse practitioner, Bennett’s teenage patients would sometimes ask if he had a few minutes to talk.

“Even though many of them had exhausted a lot of treatment options, they still found something in their life to be hopeful for,” Bennett explains. “If living disease-free was not an option, they were still able to cognitively reframe and find a different goal that they hoped for.”

In newly published research, Bennett and his research colleagues studied the experience of hope in adolescents and young adults (AYA) living with an advanced cancer diagnosis. Using creative art to facilitate communication, they found that art activities may be used as an assessment tool for psychological and/or existential distress symptoms. Art was used to explore how AYAs who have advanced cancer cope with an uncertain future and experience trauma.

“A lot of times, people default to hope for a cure being the only kind of hope,” Bennett says. “But as a lot of our study participants went through their treatment course, their hopes evolved and they found different things to hope for, and the experience of art helped them express that.”

Drawing hope

The idea for the study grew from those 1 a.m. conversations in the PICU, Bennett says. During one memorable conversation, a 17-year-old patient was talking about stopping treatment and what he wanted his final days to look like, “and interestingly his hopes were not for himself, but his hopes were focused on his family, focused on ‘I want my sister to be OK without me and I hope my parents are going to be OK and they stay together after I’m gone,’” Bennett recalls. “In just minimal parts of that conversation did he talk about himself.

“We really wanted to get to the root of what is hope for AYAs who have advanced cancer – how do they conceptualize it, how do we promote it, and clinically how do we foster that.”

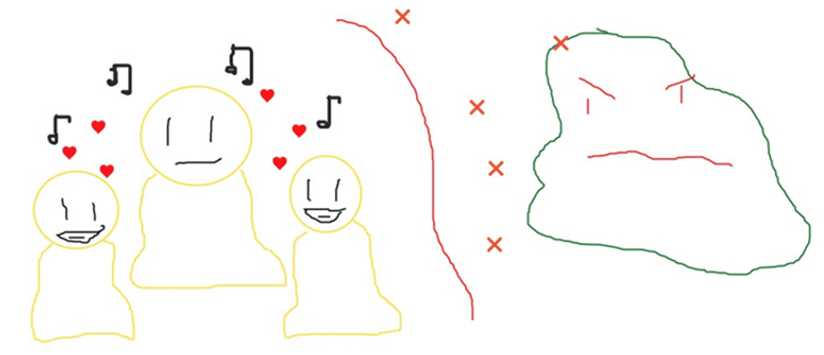

A drawing by a research participant titled "How My Family Helped Me Cope with Cancer" illustrates how family helped the participant keep negative thoughts and feelings at bay.

From his experience working with AYAs, Bennett knew that verbal expression may not come as easily for some, so he and his research colleagues explored ideas about art as a stimulus for expressions of hope. One of his co-researchers was CU Cancer Center member Jennifer Raybin, PhD, RN, CPNP, associate adjoint professor of pediatrics in the CU School of Medicine whose research interests include pediatric palliative care and creative arts therapy.

Bennett and his co-researchers designed a descriptive qualitative study that included several semi-structured interviews with participants. During the interviews, conducted via Zoom, participants generally used a digital drawing tool to create visual representations of their lived experiences with hope, discussing the art’s meaning during and after its creation.

Over the rainbow

“We found that participants were very intentional about the art they drew and the message they were trying to convey,” Bennett explains. “That manifested in how they used specific colors in what they were drawing, and in using a lot of different imagery and metaphors. We found some very deep and profound messages that they were trying to convey that words alone were not sufficient to express.”

For example, an 18-year-old female participant with stage 2 non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma created a drawing of a rainbow spanned over three trees, with dark clouds hovering over the middle tree. She explained, “The first tree represents myself pre-cancer, I was doing great but did not have any challenges and therefore did not have all the valuable life lessons that I have learned from those challenges. It's doing great, but it doesn't really know how much better it can be doing or how much worse it could be doing.

“As my cancer diagnosis struck, we moved to the second tree with lots of dark clouds. From the perspective of this tree as you can see the rainbow is not very visible, and this overarching rainbow represents hope. But, because of the dark clouds, the tree (representing myself) has to send down roots in order to survive... The clouds lighten up, and with storm clouds comes rain.

“With all these challenges came the coping mechanisms, the relationships, and the endurance that I have learned, and that has helped me flourish. I still have this root system in the third tree plus a couple of flowers, the sun has come out again, and the rainbow is still very visible. But now it has the sunshine back, and it's really going to grow bigger than it ever thought it was possible.”

The researchers discovered through participants’ drawings that familiar objects provide comfort, that the balance found in each drawing may be an attempt to regulate situational distress, and that treatment efficacy was a significant source of hope for participants.

Putting experience into words

The insights gained through the research indicate potential to use creative art in research and clinical settings to help AYAs express their thoughts and concerns beyond what they articulate verbally. It also may help them recognize patterns in their lives and discover personal meaning from their experiences, Bennett says.

A drawing titled "Not Losing Hope" illustrates a research participant's experience holding on to hope.

“One thing I noticed in these interviews was a tension between hope and still living with the unknown,” Bennett says. “Many participants talked about not knowing whether a relapse might occur or what the rest of their lives might look like, and some participants said that tension between hope and uncertainty made them uncomfortable.

“The drawings don’t quite tell the story just by looking at them, but the explanation behind them is really what tells the story. Creating these drawings elicited this back story and helped them put into words profound experiences.”

The top image, created by a research participant, is titled "The Hard Road to Your Happy Place"