Carey Candrian, PhD, knew the statistics.

“Nearly 50% of older LGBTQ adults say their doctor doesn’t know that they’re LGBTQ, and the stress of hiding takes up to 12 years off their life,” Candrian says. “Seventy-six percent of LGBTQ older adults fear having adequate support as they age. Thousands still experience discrimination, harassment, and abuse when seeking or living in senior housing. These are big numbers.”

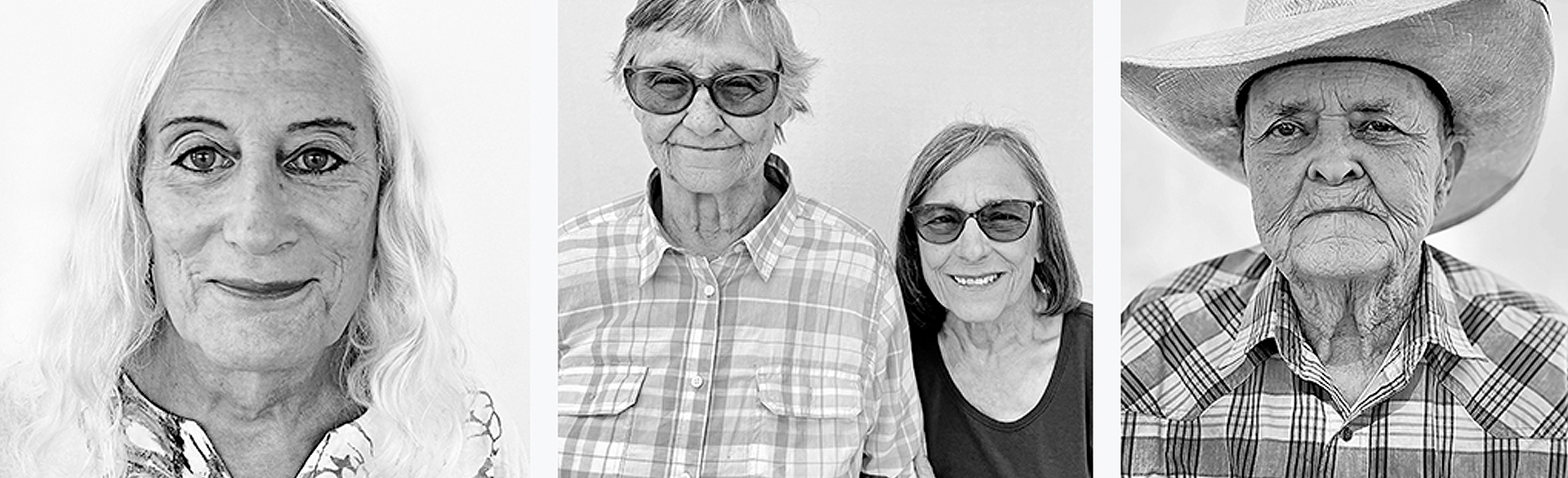

But two years ago, when — as part of a project backed by the Lesbian Health Fund and the Colorado Health Foundation — Candrian began interviewing older LGBTQ women in Colorado about their health care experiences, she began to see beyond the statistics. She met women ages 60 to 84, from throughout Colorado, who had jobs, partners, hobbies, passions, lives. Urban women. Rural women. Black and Hispanic women. Trans women. Disabled women.

Women whose stories Candrian wanted to tell.

“It’s easy to look away or disconnect when you hear general numbers about groups of people, but it’s harder to do that when you actually meet someone,” says Candrian, associate professor in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “These women have been so silent to stay safe and hidden, but they’re also really strong and brave and want to be heard.”

Revealing portraits

Candrian is telling their stories in “Eye to Eye: Portraits of Pride, Strength, Beauty,” an exhibit opening Thursday, October 14, at the Fulginiti Pavilion for Bioethics and Humanities on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. The show features Candrian’s photo portraits of 20 different women, accompanied by quotes about their struggles being LGBTQ at a time when coming out could mean losing your job, your home, or even your family and friends.

“I denied myself for 40 years. Next 40 I became who I am. Now I have a life to live.”

“The hardest part was when she was dying, and I couldn’t say we were married. We were together 33 years.”

“The purpose behind the exhibit is to be able to meet people behind these numbers, to show how real people’s lives are affected by these statistics,” Candrian says. “If you go to the exhibit, you actually will feel like you're looking eye to eye with these older women. And the quote will give you a sense of their story.”

Health care concerns

Those stories include struggles with health care, whether concerns over hospice and assisted living, OB/GYN care, or getting family support with a difficult diagnosis.

“It really does affect not just their lives, but it affects health outcomes big time,” Candrian says. “If you’re afraid your care will suffer if you talk about who you need in the room, who your advocate is, who can speak for you, who needs bereavement support — this has major consequences on mental health, physical health, and actual health outcomes.”

Carey Candrian, PhD

Carey Candrian, PhD

It’s an area that’s long been a research specialty for Candrian, with publications in The Journal of Women and Aging, The Gerontologist, The Journal of Palliative Medicine, and elsewhere on the unique experiences of LGBTQ women in the health care system.

“A lot of them did share stories, whether it was outright discrimination they've experienced with the health care system or fear of coming out,” she says of her recent studies funded by the Lesbian Health Fund, the Colorado Health Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health. “A lot of them have a mistrust of the health care system. Until 1973, they were told that they have a mental illness by the American Psychological Association. So a lot of them put off routine care, which has health consequences.

“When they already have that fear coming into the health care system, if providers start asking, ‘Wife’s name?' 'Husband’s name?’ ‘Is your family in the waiting room?’ they shut down pretty quickly,” Candrian continues. “It puts the burden on them to have to be the one to keep coming out. I think people underestimate just how hard that is and how much it matters, particularly when you are sick and scared.”

Similarities and differences

That’s why Candrian makes it a point to teach her palliative care students the importance of being sensitive to potential differences in patients, and it’s why she put the "Eye to Eye" exhibit together, as a reminder that differences are all around us, even when we can’t see them.

“I hope it stays with people,” she says. “This exhibit is not going to give 12 years back to anyone’s life, but after you see these women, after you read their quotes, I hope it makes people think differently when they interact with patients, or a colleague, or a friend. Because that’s a good start.”

“Eye to Eye” opens with a reception from 4–6 p.m. October 14; an RSVP is required. Regular gallery hours are 9 a.m.–5 p.m. Monday–Friday. Visit the exhibit page for more information and to RSVP for the opening reception.