Kia Washington, MD, looks back on her undergraduate experience as four years that helped to shape who she is. One of those years in particular stands out as not just formative, but transformative.

As a young Black woman who grew up attending mostly white schools, it was important to Washington to experience more diversity when she went to college. One reason she chose to go to Stanford University in California was the school’s exchange program with Spellman College, a historically Black women’s college in Atlanta. Washington spent one year there.

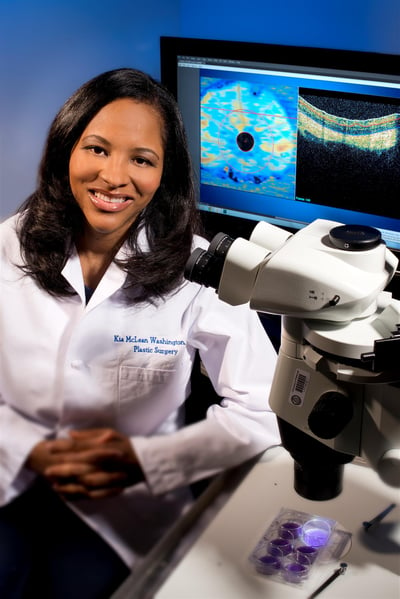

“It was important to me to have that experience of being in an academic community where I wasn’t the minority,” says Washington, director of research and professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “It was very affirming to have classes where the teachers were all Black women and all the other students in the class were Black women.”

Raised by parents who had moved to Washington, D.C., from the Jim Crow South to attend Howard University, Washington led a double life of sorts as a child — D.C. had a vibrant and affirming Black community, but much of her time was spent in a predominantly white elite private school, Sidwell Friends, which was attended by children of Presidents Obama and Clinton. She found her Black community at Stanford, but the majority of her fellow undergraduates were white. The same goes for her medical career, where she often has felt she had to hide parts of herself in order to fit in.

“In certain institutions, it has been hard to have a sense of belonging where I could totally express my authentic self, because I’ve often been the only one.” - Kia Washington, MD

“In certain institutions, it has been hard to have a sense of belonging where I could totally express my authentic self, because I’ve often been the only one,” she says. “Has it been difficult? Yes. Has it been something that’s crushed me or defeated me? No, because of what my parents instilled in me and the awesome educational background I received.”

As vice chair of diversity and inclusion in the Department of Surgery at the CU School of Medicine, Washington is now on a mission to radically improve the experience for young doctors from underrepresented backgrounds in medicine, looking to substantially increase their numbers in the department.

“It adds value,” she says. “A lot of studies that have been done, specifically in the business world, show that diversity increases overall productivity. More importantly, in medicine, it improves your outcomes for your patients when you have a diverse workforce. Our motto as a department is ‘Improve Every Life,’ and in order to improve every life, we have to improve the lives of those who are most vulnerable. They need to see their faces reflected in the people who take care of them.”

A higher calling and finding her own way

Raised in the D.C. suburbs of Silver Spring and Beltsville, Maryland, Washington grew up a tomboy who competed in sports like her two older brothers, eventually playing NCAA soccer at Stanford. Her interest in medicine grew out of her early love of animals — at age 5 she decided she wanted to own a pet store when she grew up; when she got a little older, she thought about becoming a veterinarian.

“When I was in middle school, I realized I’d rather do something that involved working with people,” she says. “The intellectual and service aspects of medicine appealed to me, and the ability to help heal someone’s body. It combined everything I thought I wanted in a career.”

Still, when she arrived at Stanford she chose to major in English literature, with a particular focus on African American writers such as Toni Morrison and Langston Hughes.

“I did think about a career as an English professor; in fact, at the end of college, I was choosing between that and medicine,” she says. “The idea of teaching in a classroom didn’t appeal to me as much, but the idea of writing a book really appealed to me, and I hope to still do that one day. Still, medicine called me in some way. I felt compelled to do it.”

Passion for creativity and innovation leads to plastic surgery

When she entered Duke University School of Medicine, Washington initially felt at a bit of a disadvantage — as an English literature major, she didn’t have the same heavy science background as many of her peers. “But those skills I learned as an English major definitely paid off later — being able to write and express my ideas helped in research and writing grants.”

She also found a welcoming community at Duke, thanks to pioneering administrator Brenda Armstrong, MD, who was among the first African American undergraduates at the university and who became an influential contributor in expanding the diversity of the American physician workforce.

“She was a phenomenal pediatric cardiologist who ended up being a great mentor at the time,” Washington says. “Growing up, I learned about many of the hardships my parents had as children in the segregated South, and I was reluctant at first to go to Duke for medical school. But I had a huge support network there, which made it a lot of fun and helped me to get through.”

It also was at Duke that Washington chose her specialty of plastic surgery, inspired by the ability to change lives through reconstruction.

“I actually thought I wanted to go into OB-GYN, in particular gynecologic oncology,” she says. “But I also realized I like variety. Someone advised me to do a plastic surgery rotation, and I really loved it and I didn’t turn back. I loved the creativity of the field, the innovation, the ability to operate all over the body. Those were the things that appealed to me.”

From Pittsburgh to Denver and setting herself apart

Washington’s next stop after Duke was the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, where she spent three years as a general surgery resident before an additional three years as a plastic surgery resident. She served one year after that in a hand surgery fellowship. William Futtrell, MD, who was chair of the school’s plastic surgery department during Washington’s time there, says the school felt fortunate to have Washington in its program.

“The way we get excellent students at Pittsburgh is we go out and recruit,” Futtrell says. “When I started looking into Kia’s background and talking to people, both at Duke and at Stanford, everybody was just over the top in saying, ‘This kid is special.’ I’m sure Kia could have gone anywhere she wanted to. We were delighted to get her.”

As a resident at Pittsburgh, Washington didn’t only train to become a plastic surgeon; she spent two years at the University’s Starzl Transplant Institute, where she began groundbreaking research into facial and eye transplants that eventually won her a $6 million grant from the Department of Defense — and the admiration of her peers.

“Plastic surgery is a really intense training; it’s really extraordinarily long,” says Angela Landfair, MD, a plastic surgeon who trained with Washington in Pittsburgh. “I was in survival mode as a resident, and I think most people were in survival mode. But somehow, during this very intense training period, she managed to have a totally separate parallel life and purpose in research. She had great mentors, but she had to take what she could learn from these various mentors and create something that was entirely her own. No one was doing what she was doing at the time. And to do it during residency? That’s incredible. A lot of people don’t have that kind of drive.”

Washington brought her eye transplant research team with her to the CU School of Medicine when she arrived in 2018, along with the wide-awake hand surgery program in which doctors perform common procedures like carpal tunnel release and trigger finger release on an outpatient basis, using local anesthesia, to conserve resources and save patients time.

“When I started looking into Kia’s background and talking to people, both at Duke and at Stanford, everybody was just over the top in saying, ‘This kid is special.’ I’m sure Kia could have gone anywhere she wanted to. We were delighted to get her.” - William Futtrell, MD

“It’s part of what’s called the ‘Lean and Green’ hand surgery movement to minimize waste in hand surgery,” she says. “A lot of procedures in hand surgery can be done with just local anesthesia. They don’t need to be done in the operating room where you’re using a lot of resources, like an anesthesiologist, extra drapes and things like that. It’s nice to move them to a more efficient space.”

For those innovations, her work to increase diversity and more, Washington has become a valuable member of the CU School of Medicine team as the school continues to grow its reputation locally and nationally.

“Dr. Washington is a natural leader who has great insight and always a calm way of getting people on the same page,” says Richard Schulick, MD, MBA, chair of the Department of Surgery. “She is a great clinical surgeon, distinguished researcher, and sought-after teacher. We are very proud to have her as one of our department leaders.”

Using her voice and experience as a platform for change

As the first Black female plastic surgeon in the country to hold the title of full professor, Washington has seen things change for physicians from underrepresented backgrounds in medicine — but she knows there is still a long way to go. As painful and horrifying as 2020 was for the Black community, with the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and more, Washington sees it as a long overdue reckoning that is beginning to move the needle on awareness around issues of equity, implicit bias, and microaggressions.

“My goal, especially in the work I do with diversity, is that people can belong. They don’t have to try to fit into a system; they can be who they truly are and bring their unique talents to the table.” - Kia Washington, MD

“My father always taught me you have to be three times as good to succeed as a Black woman, which was empowering because I knew I would always have to work hard,” she says. “And I did. I worked hard, and I excelled. The flip side to that is it’s also a lot of pressure. You don’t take as many risks when you feel like you don’t have a safety net under you that you may have when you’re from a different group. Also, when you’re often the only one, you feel like the spotlight is on you. That can be daunting at times.

“My goal, especially in the work I do with diversity, is that people can belong,” she says. “They don’t have to try to fit into a system; they can be who they truly are and bring their unique talents to the table.”

That might be a tougher task in Colorado, which isn’t exactly known for its diversity, but Washington is up for the challenge. As head of the surgery department’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee, she is helping to examine everything from hiring practices and trainings to mentorship and patient care. A DEI lecture series kicked off February 22 with Robert Higgins, MD, surgeon-in-chief and chairman of the Department of Surgery at the Johns Hopkins Hospital; the committee’s long-term goals include increasing diversity in leadership positions, increasing mentorship opportunities for faculty members of color, and creating an environment that faculty and staff feel is inclusive.

“Historically, academia and surgery are institutions that were primarily white and male,” Washington says. “The challenge is overcoming that history and deconstructing that system to bring more diverse voices into the community. It’s hard to be from an underrepresented group in surgery, and I think that can be discouraging at times.”

On a personal level, she worries about her two daughters — ages 6 and 8 — finding the culture and connections they need to thrive.

“I was fortunate to grow up in D.C., which at the time was a predominantly Black city. I had that nourishment and enrichment I needed for my soul as a Black woman at a young age,” she says. “It’s more concerning for me raising two Black girls here. I worry about it — is this going to be detrimental for them? I talk to a lot of people, including my friends at home, and they say, ‘Don’t worry; you’ll instill enough in them,’ enough Black culture and the pride I have in being a Black woman, and that will resonate with them. Also, times are very different than when I was growing up. They get a lot of affirmation at their school and from their peers. They are often surrounded by people who openly say ‘Black lives matter.’

“My hope is that they will have what they need to thrive as Black women,” she continues. “They call it Black girl magic for a reason. It takes a lot of magic and resilience to thrive and find joy. They are free, creative and spirited little girls. A lot of the reason I do the work that I do is so that they never have to fit in or have their success defined by others. I want them to have the freedom to fully express themselves. That’s a benefit to everyone in society, when people can fully express themselves as creative beings.”

For those who know Washington, there is no doubt she will continue to spread her magic through the CU Anschutz community and beyond.