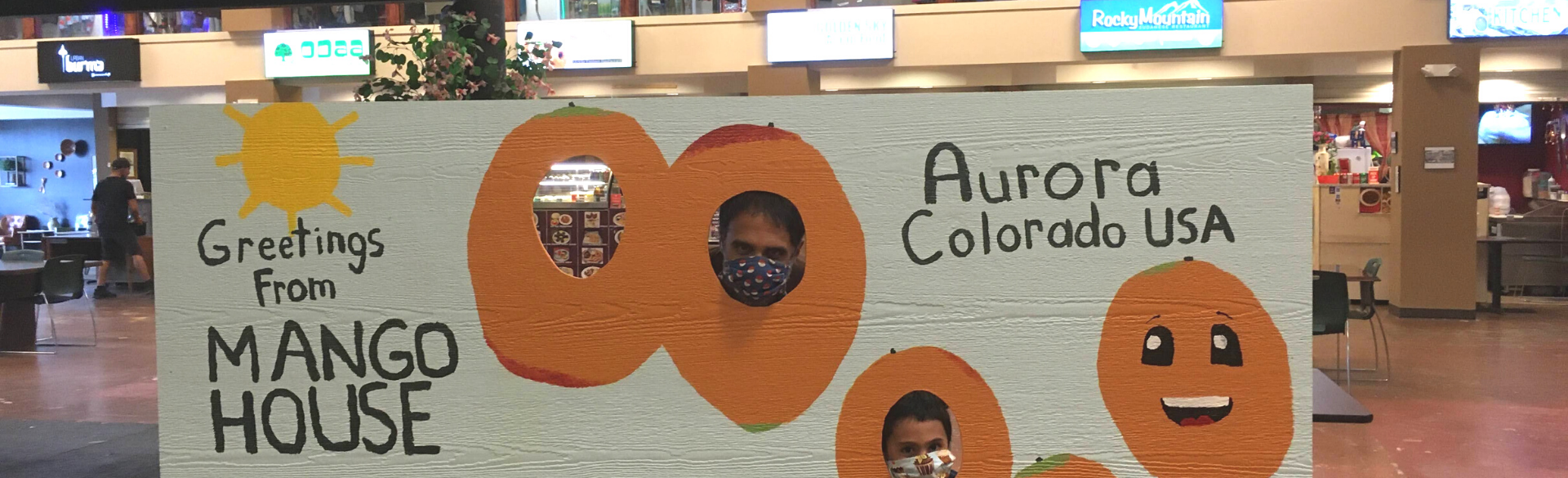

What started as a way to provide affordable medical care to Denver’s refugee population has grown into a home away from home for those who are far away from home.

Mango House, founded by University of Colorado School of Medicine alumnus P.J. Parmar, MD, ’08, houses a medical clinic, a dental clinic, and a pharmacy, but it also is home to an international grocery store, a Nepalese boutique, and an array of six refugee-run food stalls offering authentic cuisine from Syria, Ethiopia, Sudan, Nepal, Burma, and more.

Located in a former JCPenney store on Colfax Avenue in Aurora, two miles from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Mango House was born of Parmar’s desire to help the medically underserved.

P.J. Parmar founded Mango House to provide medical care to refugees. Photo by Ross Taylor.

P.J. Parmar founded Mango House to provide medical care to refugees. Photo by Ross Taylor.

It’s a passion that led him to an abrupt career change in 2004, when he left his job as an environmental engineer to attend the CU School of Medicine. After completing his residency at St. Anthony North Family Medicine in Westminster, Parmar opened a small clinic devoted to providing care for the refugee population in east Denver and Aurora.

“I knew I wanted to work with an immigrant population, and the least served of the immigrants are the refugees,” says Parmar, the son of physicians from India who emigrated to Canada before moving to Chicago.

Open door policy

From the beginning, he expected to do business differently. Most of his patients depend on Medicaid, and all appointments are on a walk-in basis.

“If you’re poor, you don’t have a car. You don’t have phone minutes to make an appointment. You can’t leave your job to go to an appointment,” says Parmar, who gave a TED Talk on the topic in 2018.

“These are not the first things that come to mind for people who actually have the privilege to get in the car and go somewhere on time for an appointment, or to sit on hold and listen to elevator music and ‘press 1 for this,’ and speak enough English to understand what that means. There are so many steps between A and B, instead of just saying, ‘Yes, come in. We’re here, period.’”

Onward and upward

Parmar’s clinic on Leetsdale near Cherry Creek lost its lease in 2014, and he set out in a new direction.

“I decided to move my business to where the refugees are and find other businesses that wanted to join me,” he says. “And I wasn’t going to be kicked out of the building again; I was going to buy the building and manage it.”

His first landing place was on Galena Street just off Colfax, but he soon began eying the former JCPenney location, which was five times bigger and already outfitted with the rough construction for six food stalls.

Mango House is now a community center that houses Parmar’s Ardas Family Medicine and his dental clinic and pharmacy, as well as restaurants, stores, spaces for religious and community organizations, and a Boy Scout troop Parmar leads, made up of children of refugees. The restaurants are a draw for curious neighbors and residents from nearby communities.

Mango House is home to six refugee-run food stalls offering authentic cuisine from Syria, Ethiopia, Sudan, Nepal, Burma, and more. Photo by Ross Taylor.

Mango House is home to six refugee-run food stalls offering authentic cuisine from Syria, Ethiopia, Sudan, Nepal, Burma, and more. Photo by Ross Taylor.

“When we were in the other building, people started saying, ‘What’s going on here? How do we learn what’s going on, bring our kids to learn, and how do we get involved?’” he says. “With the refugee restaurants, customers can come and sit there, and they can get that feeling that they want, or they can sit around and learn.”

The result, he says, is “a community that I enjoy, and by the looks of it, one that a number of other people enjoy, including many ethnic backgrounds, including Americans.”

Centered on community

At the heart of it all remains Parmar’s passion for serving refugees and immigrants. It’s a passion born partly from his own experiences with racism.

“When you’re subjected to enough of that yourself, it becomes a mission to help the minorities who are on the receiving end by bridging any part of their life that you can,” he says. “By being a bridge between whatever culture they came from and the American society.”

That accounts for the nonmedical segments of Mango House — the aspects that have turned the former department store into a treasured community resource.

“The medical care makes the money around here, but it’s not the point,” he says. “In family medicine, I’ve always thought it’s more about the family than the medicine anyway. At Mango House, we have tons of things that speak to those other parts of a person and of a community — of many communities.”