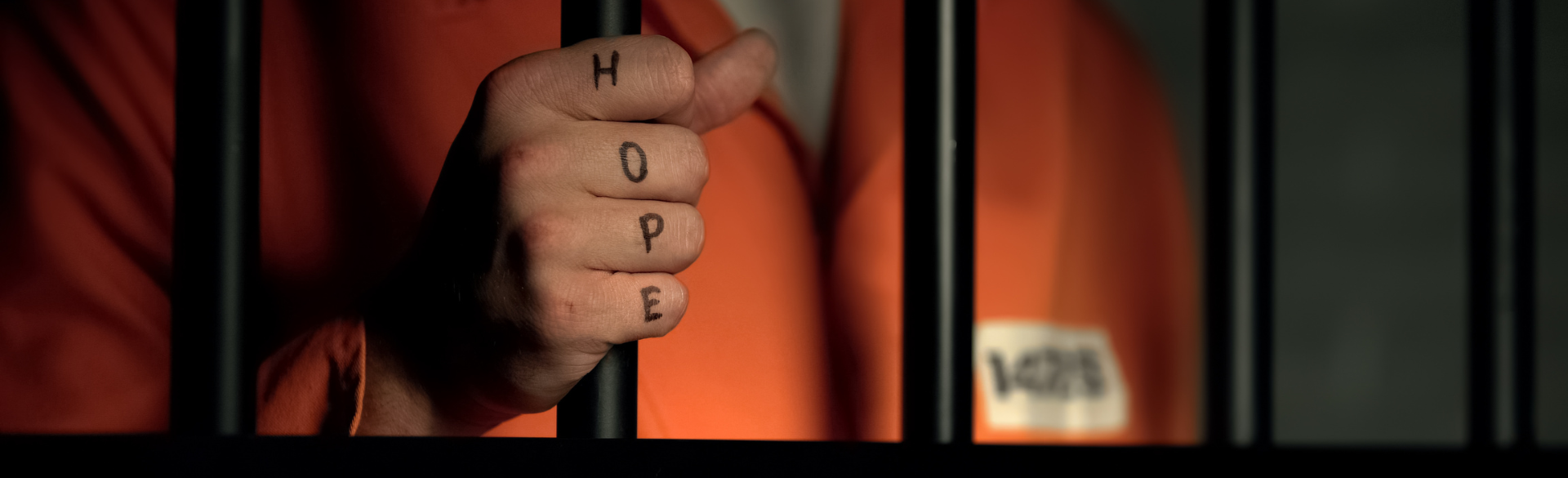

Getting released from jail can be a lonely, isolating experience. With release dates often unknown until they happen, and virtually no formal support systems in place for those released from jail as they reenter the community, many must navigate their new world alone. It’s no wonder that the risk of death becomes dramatically higher in the two weeks after jail release — from causes including suicide, homicide, overdose, and cardiac events.

The new Wellness, Opportunity, Resiliency Through Health (WORTH) program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine aims to help with that transition, and to empower people to better manage their health care needs after release and while they are still incarcerated.

“We attempt to support and assist them in that, connecting with people while they’re inside and continuing that connection when they’re out,” says Jessie Henderson, WORTH’s peer support specialist. “We want to empower them to connect to their health care, which also involves connecting them to housing and other resources and being a support system for them regarding the anxiety and other issues that have to do with incarceration.”

A collaborative effort between the CU School of Medicine and Colorado’s Department of Health Care Policy and Financing, the WORTH program facilitates access to community-based medical care and social support for individuals detained in or recently released from a county jail. Led by a staff of four — Henderson, heath navigator Angel Soto, medical director Josh Barocas, MD, and program director Megan Robins — WORTH looks to address a number of medical challenges inherent in the county jail model, including a lack of specialists, often a lack of onsite medical care in the facilities, and a care system that is completely separate from the community.

There is no continuity of care for those who are treated in jails, Robins says — they are typically released with no medical records, no prescriptions, and no follow-up treatment scheduled.

“Let’s say they started having seizures while they are in jail,” Robins says. “If they’re lucky, they get to see a doctor from the jail who may or may not be able to do a workup. Then they get released from jail, and there’s no appointment scheduled, there are no medical records in hand, no medications on hand — sometimes the people don’t even know what medications they were on. Then if they arrive to a new doctor’s appointment in the community, the doctor has no idea what happened at the jail. It’s completely duplicative. Not only is it frustrating for the patient; it’s hugely frustrating for the provider. Now we’re billing Medicaid for services that were done two weeks ago in the jail, but we don’t have access to it. We want to make all this much more streamlined.”

Building relationships and overcoming stigma

As a health navigator for WORTH, Soto begins building relationships with participants while they are still in jail, talking to them about their health goals and their past experiences with health care. As people in jail are more likely to have mental health and drug abuse concerns than the general population, Soto keeps those issues in mind as she connects participants with care that is most likely to be effective.

WORTH program team Angel Soto, Jessie Henderson, and Megan Robins.

“A lot of the folks we work with have had traumatizing experiences in the medical setting and have felt unheard and stigmatized because of their past and/ or current drug use,” Soto says. “They often feel they don’t get quality care because of what they’ve been through or what they’re currently going through.”

Soto works to make participants feel more comfortable receiving care, connecting them with providers who have experience treating patients with mental health and substance abuse issues. She will even accompany them to appointments and work with them to better understand their overall health situation.

“I educate them about their medical conditions and how to navigate the health care system — about health insurance, how to obtain medical records, how to advocate for their own health,” she says. “We work toward getting the participant in a place where they feel in control of their own health care and have the knowledge to make the choices that’s right for them.”

For program participant Keegan Hill, of Aurora, WORTH has been an important partner in getting the health care he had put off for years.

“Just to know there’s somebody out there that has your back, to make sure your basic needs are being cared for, whether it’s getting to an appointment, getting home, or making sure you’re feeling safe enough, even with yourself, to go to the doctor” is an important part of what WORTH offers, he says.

Barocas, associate professor of internal medicine, says he was drawn to the program because of his previous work with vulnerable populations, including people with substance use disorders and those experiencing homelessness or who have been incarcerated. He has seen firsthand the barriers that can arise.

“So many people can’t access health care because they can’t navigate it. How can you show up at a doctor’s appointment if you don’t have a telephone or don’t have reliable transportation?” he says. “Why would you come back to see a doctor if they treat you without respect? When Megan and I started talking about the program, it was clear that this was a missing piece in helping this population improve their health outcomes.”

Connecting with resources and providing support

In his role as peer support specialist, Henderson — who, along with Soto, has spent time incarcerated in a county jail — works to connect participants with housing, social support, and other resources. As someone who was formerly incarcerated, he understands all too well the stigma and self-doubt that come when it’s time to re-enter society.

“For some people, it can be extremely difficult to call a landlord and explain their background,” he says. “We can help them through that or go with them to meet the landlord and figure out how we help. Some people need more extensive support, and some people you could just give them a phone number. But we don’t want to be the people that just give you a phone number. We want to say, ‘We know who this person is, and we know they’ll respect you. We’re going to direct you to them so that you are treated the way you should be treated, no matter if you were just released from incarceration, no matter if you’re using drugs, no matter what the situation is.’”

The primary goals of the WORTH program are to connect participants with medical care, housing, and other resources, but a secondary goal, the staffers say, is to provide a sympathetic ear to people going through what can be an extremely difficult transition.

“As people who have also lived in that experience, we’re able to relate and reflect with them,” Henderson says. “It can be something as simple as having a conversation and getting down to the nitty gritty of, ‘Where does your fear come from? And how can we set goals to overcome that fear and move you through it?’”

“I was working with an older gentleman once, and he actually started crying,” Robins recalls. “He said, ‘I’ve never had someone care about my health before, so I’ve never cared.’ There’s power in just sitting there and saying, ‘If you have questions, I will hear you, and I will answer them.’”

Hill has found that aspect of WORTH to be a valuable part of keeping him connected with the program and what it offers.

“It’s somebody to talk to —they lean on us, we lean on them,” Hill says. “It’s not just the basic, hardcore needs; they’re paying attention to the underlying stuff as well.”

Building collaboration with hopes to create more connections

In existence for less than a year, WORTH is still improving its plans and finding new ways to aid its participants. Part of that equation involves working with community medical centers and medical teams inside jails to increase communication and collaboration, Robins says.

“We want to help providers in the jails and the community clinics provide better care and create more continuity,” she says. “Right now, both of those parties are isolated. It’s hard to offer the full spectrum of care. If we can bridge that gap of communication and relationship-building, we can bring everyone together and offer a full continuum of medical care for the individual. The medical staff in the community clinics and the jails are important stakeholders here, too. We’re trying to be that bridge to decrease the complexity, to help providers feel more support and be able to do their job better. And that means our participants are getting better care as well.”

WORTH plays a vital role for incarcerated individuals who often have no other support when it comes to accessing health care in the community, Barocas says.

“This is a population that loses their health care when they enter jail,” he says. “This is a population that is disproportionately affected by substance use disorders, trauma and violence, poverty, and untreated mental illness. There are a cadre of health outcomes that are, in turn, affected by these social determinants of health. Aspirin may help with heart disease, but access improves health. Everyone deserves the opportunity to live their healthiest life.”

As the WORTH program grows, Robins hopes to hire more navigators and support specialists, to work with more jails, health provides, and other community resources, and to share the lessons she has learned with other state-sponsored programs that have similar goals.

“This program came about because we recognized that someone’s ability and desire to engage in medical care is so relationship-based,” Robins says. “If people don't feel safe accessing medical care, then they’re not going to. The whole point here is to repair the relationships that the medical system has broken down with certain populations. We do that through resource navigation, but a lot of it is just being with people. There’s empowerment that comes from having a caring relationship with someone who knows what you're going through and is in your corner.”