Representation matters.

On a recent day in her pediatric pulmonary clinic, the first patient Jennifer Taylor-Cousar, MD, saw was a 10-year-old girl who is Black and who asked if she could keep the disposable gloves and stethoscope used during her appointment. She wants to be a doctor, just like Taylor-Cousar.

“Representation matters,” Taylor-Cousar, a professor of pulmonary sciences and critical care in the University of Colorado School of Medicine, repeated Thursday afternoon as the keynote speaker during the White Coats for Black Lives Die-In. The annual event, which occurs nationwide and was hosted Thursday by the CU School of Medicine chapter of White Coats for Black Lives, is held as a protest and to commemorate the lives lost to structural racism and racial injustice. It spotlights the work the health care profession is and must be doing to address racism and discrimination.

“We have to be visible on campus,” said Rachel Ancar, a fourth-year medical student and co-president of the CU School of Medicine chapter of White Coats for Black Lives. “We need to be there for our patients, and it’s so important that they can see themselves represented in us as their caregivers.”

“We must keep rising”

In her keynote address, Taylor-Cousar began by noting that “we went into medicine because we wanted to help people. We wanted to improve their lives regardless of their background.”

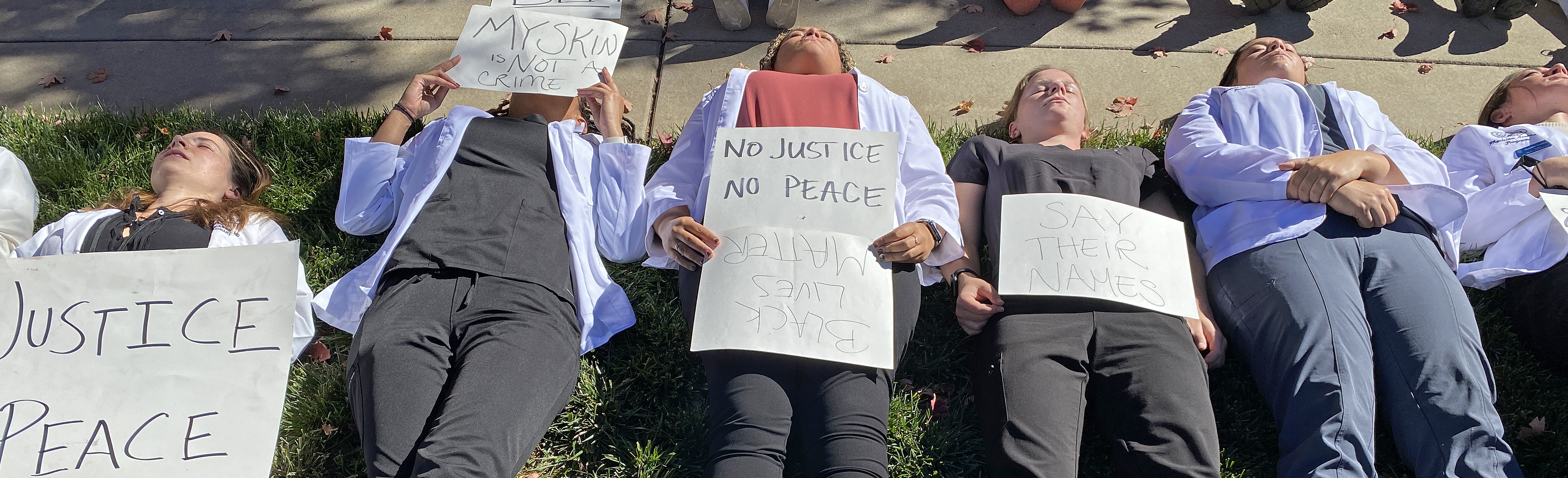

Participants in Thursday's White Coats for Black Lives Die-In spotlighted issues of structural racism and racial injustice in health care.

Help is not just for patients of color, but clinicians of color. Taylor-Cousar spoke about how medicine in the present day is inextricably linked to the history in which the ship White Lion docked at Point Comfort, Virginia, in August 1619 and the shackled Angolan people aboard were forced ashore.

The first Black person in the United States to receive a medical degree was David Jones Peck, MD, in 1847 – and even in 2022, "Black people are 14% of the U.S. population but only 5% of U.S. physicians are Black,” Taylor-Cousar said. “It’s critical that changes. Representation matters.”

She also highlighted a 2020 University of Pennsylvania study that found patient satisfaction is higher when there is racial concordance between physician and patient.

As one of an extremely small number of tenured full professors in the United States who are Black and female, Taylor-Cousar emphasized that she can use her voice to represent people who have been left out of or misrepresented in research and in medical care. As a cystic fibrosis researcher, she has conducted studies that highlight how the disease impacts all races and communities, not just people who are white, and emphasized the vital need for racial justice in medical care.

“For those of you currently in training, I wish I could tell you the adage that you have to work twice as hard is a relic of the past, but it isn’t,” Taylor-Cousar said, before reading Maya Angelou’s seminal poem “Still I Rise.” “We must keep rising; we must keep representing. Our Black patients’ lives depend on it.”

Health is a human right

Fourth-year medical student Ephrat Fisseha, MPH, shared some of her experiences as a woman of color and a woman of Ethiopian heritage in a poem she wrote.

“When I was a little girl, I never learned to wear my lineage like a crown,” she said. “In school I learned that history began with the white man, even though I came from the cradle of humanity.”

She spoke of never learning as a little girl “how dangerous it is to wear dark skin. I have died too many deaths that were not my own.” However, in a thought with particular relevance to her medical colleagues, she noted that “Blackness is alchemy, the way we see ourselves in each other.”

Dozens participated in the annual White Coats for Black Lives Die-In Thursday on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus.

Her words resonated through the climax of the Die-In, when those in attendance lay in silence on the grass or sidewalk for eight minutes and 46 seconds, the amount of time that Minneapolis police officers knelt on George Floyd’s neck on May 25, 2020, causing his death.

The silence in the middle of a bright, blue-sky autumn day was loud with the voices of each person who has endured racism, injustice, and exclusion in various facets of their lives, including seeking and receiving health care.

At the close of the Die-In, those in attendance read “Pledge to Our Future Patients,” written in 2020 by members of the CU School of Medicine chapter of White Coats for Black Lives. The pledge states that “we see injustices every day in access to and delivery of care, health disparities, poverty, violence, education, and the criminal justice system. We acknowledge that these injustices affect your daily lives. Recognizing that health is a human right, we reaffirm our commitment to you.”