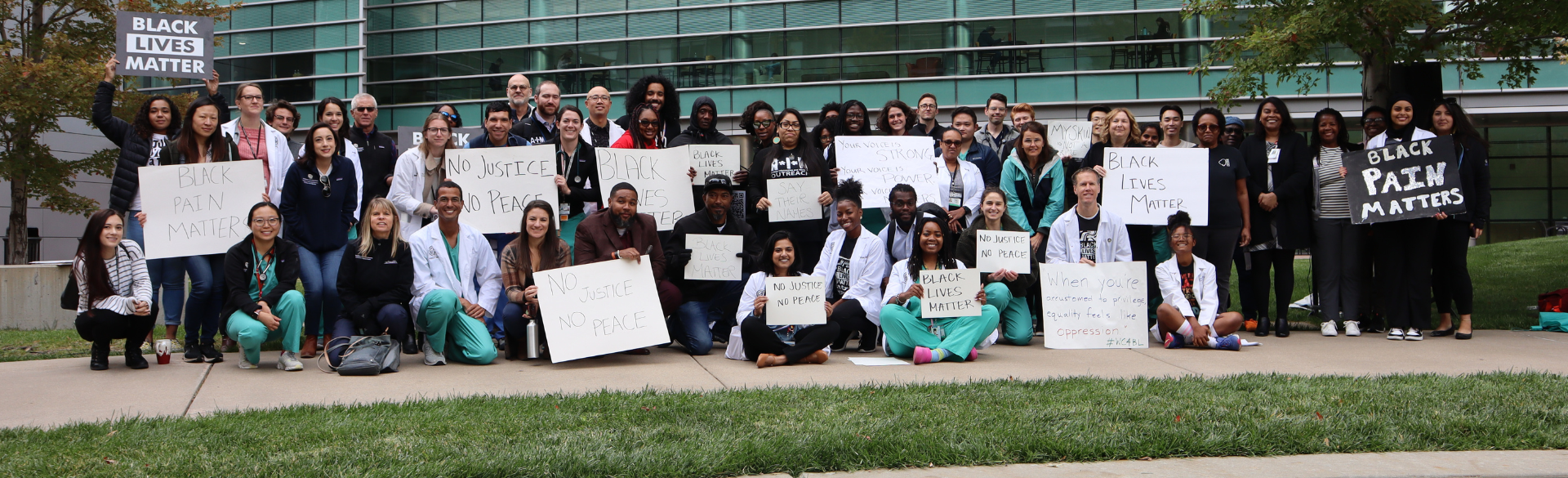

A light rain began to patter on the yellowing fall leaves as, one by one, dozens of people – many in white lab coats and green scrubs – lay down on concrete benches or the grass. Others sat with their heads bowed, as if to meditate, or pray, or ponder the pain and injustice that had brought them there.

Surrounded by the gleaming towers and verdant beauty of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus’ Research Quad, Thursday’s midday gathering had a somber purpose. People lay prone for exactly eight minutes and 46 seconds – the amount of time a police officer pressed his knee on George Floyd’s neck on that brutal day in Minneapolis.

The annual Die-In was organized by the CU School of Medicine student chapter of White Coats for Black Lives, a national movement of medical students founded in 2015. Tyler “Benji” Benjamin, a third-year CU medical student who was a featured speaker, said the gathering gave students, faculty, and staff a chance to publicly “stand in solidarity with the people that we’ve lost or were otherwise impacted by this pervasive idea of hate, violence, and prejudice that seems to persist in American culture. We’re here to say it’s not OK, and we want to be heard.”

But as speakers made clear, the Die-In’s message goes well beyond Floyd’s 2020 murder at the hands of police and all the other unjust deaths of people of color through the years.

‘People of color are here’

The gathering addressed racism, injustice, and inequity in all their forms, both in society at large and in the medical profession. And part of that, the speakers said, is addressing the underrepresentation of people of color in health care.

“Having Black physicians and physicians of color increases access to preventive and primary care in communities of color,” said keynote speaker Renee King, MD, MPH, associate professor of emergency medicine at the CU School of Medicine and an emergency physician at Denver Health. “This leads to better health outcomes, including longer, healthier lives.”

King cited several examples of Black health professionals throughout history who have contributed to major advances in health sciences. “People of color are here, and we are needed to move our profession forward in an inclusive and comprehensive manner,” she said.

Race a factor in care

The question is, “What are we going to do about it?” Benjamin asked in his speech.

“Are we going to allow discrimination and bias to persist in our health care systems, or are we going to actively work to eliminate those disparities in access and outcomes for members of the Black and brown communities?” he asked.

Event leaders spoke of their struggles for achievement and recognition in an overwhelmingly white professional and academic world, and how they aspire to work toward a better, more accepting environment for those who follow in their footsteps into medicine as well as for patients of color they see as denied the full benefits of health care.

India Bonner, a third-year medical student who aspires to be a surgeon, is a leader of the campus White Coats for Black Lives chapter and helped organize the Die-In. In an interview, she spoke of her aunt, who had an injury to her lower leg that required amputation.

“There wasn’t appropriate follow-up for how to take care of the wound,” Bonner said. “They sent her home too soon. She got a really bad infection and went septic, and she passed away. I do think race had a big part in that because they didn’t give her the appropriate care.”

That experience and others led Bonner to her chosen career path.

Higher morbidity and mortality

“One of my main drivers for pursuing medicine is that I want to advocate and make for better outcomes for Black patients,” Bonner said. “Because of all the racism in medicine, Black patients get less timely access to care, they get poorer pain control, and they’re more likely to have higher morbidity and mortality in surgery, and in medicine in general. I want to use my leadership role as a physician to mitigate that, and White Coats for Black Lives allows me to do that.”

Another organizer, fourth-year medical student Medha Gudavalli, said: “Throughout my life I’ve seen how discrimination and racism can affect people on an interpersonal level but also at an institutional and larger level, where we’re seeing things like health disparities and police brutality, and that’s what drove me to White Coats for Black Lives.”

Die-In leaders blasted the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in June striking down race-conscious college admission programs, which they predicted will slow progress in continuing to diversify medical schools. They called on Die-In participants to sign a digital petition to the CU Anschutz Student Senate calling for a resolution “stating the importance of increased diversity among the student body and future health care workforce.”

To ‘our future patients’

The crowd at Thursday’s event was invited to recite aloud a pledge to “our future patients” that declared, in part:

We will challenge discrimination in our spheres of influence, both professional and personal.

We will treat you with the profound respect, compassion, and integrity that you deserve.

We will work to the best of our abilities to ensure that you are given the best care available.

As we strive to uphold these declarations, we promise to learn from our mistakes, especially those stemming from our biases, and we pledge to remember what a privilege it is to serve you.

As the gathering broke up, participant Krystal Austin, a third-year medical student on an OB-GYN path, talked of her research into maternal health disparities in the Black population by way of explaining why she came to the Die-In.

“I feel it’s super-important to continue to raise awareness and make sure that these conversations are still happening. It’s not enough to just have a training once every year and then never talk about it again. There has to be a culture of continuous improvement and discussion and acknowledging your own biases,” Austin said. “Events like this are a step in the right direction.”