Born with a rare metabolic disease that increases his risk for stroke and other cardiovascular illness — and greatly limits what he can eat — Russell Maestas is excited about research at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus that has produced the first human clinical trial of a potential cure.

Russell Maestas is taking part in the first human clinical trial of a potential cure for homocystinuria. The genetic disorder increases his risk for stroke and other cardiovascular illness

“If it’s a breakthrough, that’s absolutely fantastic,” said Maestas, a 25-year-old who, every month, drives four hours from San Luis to Children’s Hospital Colorado to participate in the clinical intervention. “Anything positive is always good.”

Historically, one-quarter of untreated homocystinuria patients died before the age of 30, but Maestas is one of the fortunate ones. His condition was discovered during newborn screening, and doctors told his parents to drastically limit his protein intake (along with nutrient supplementation, as advised by a metabolic nutritionist), one of the best-known methods of managing the illness.

Maestas shows no outward signs of the genetic disorder, which currently has no cure and can result in cognitive problems, dislocated lens, deformities of the skeleton and elevated risk for cardiovascular disease. Maestas, a social worker, has only the latter.

Decades in the making

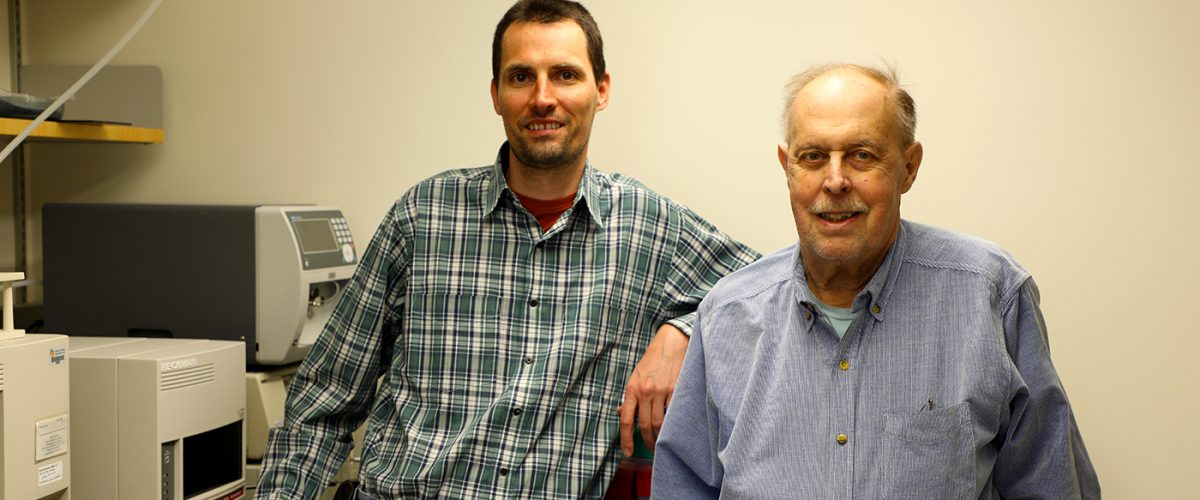

He is one of the patients joining the national clinical trial that was developed in the Section of Genetics and Metabolism within the CU School of Medicine Department of Pediatrics. It is the product of decades of research by Jan Kraus, PhD, principal investigator of the Kraus Lab and Tomas Majtan, PhD, leading scientist on the project.

“I’ve been working on this disease for over 40 years,” Professor Kraus said. “With this therapy, we hope we can keep the homocysteine levels low, or at bay, so the end result is we can improve people’s health.”

Added Majtan, “It is our wish that the amazingly consistent and very encouraging results obtained from the pre-clinical testing using several mouse models of homocystinuria will be reproduced in the first-in-human clinical trial.”

Janet Thomas, MD, who has treated Maestas for many years, praises the work by the Kraus Lab, noting that it exemplifies the bench-to-bedside ethos of the CU Anschutz Medical Campus, where top-notch hospitals are located just a short walk from the research labs.

“It’s the first time we’ve been able to take what our researchers have done and move it to a clinical intervention,” Thomas said of the genetics section of the Department of Pediatrics. “It’s really cool, especially on this scale with industry involved and a national clinical protocol.”

CU has signed an exclusive licensing and collaboration agreements with Orphan Technologies, Ltd., a rare-disease and research-and-development firm, to develop the therapy.

Increasing prevalence

Recent research has estimated the prevalence of homocystinuria in the United States may be as high as 1 in 10,000 people, as symptoms of the disease can be mistaken for those of other disorders. This number is substantially higher than prior estimates of 1 in 100,000-200,000 in the United States and 1 in 200,000-335,000 worldwide. Rates are exceptionally high in the Middle East, especially in Qatar, where the incidence is approximately 1 in 1,000.

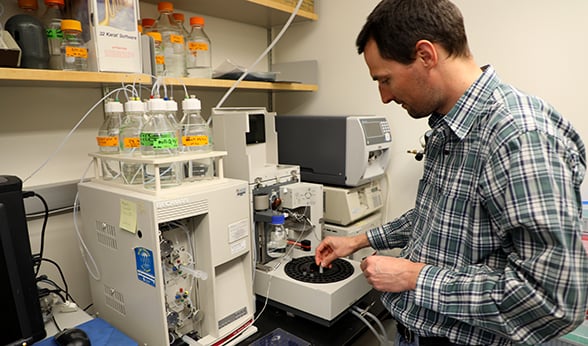

Tomas Majtan operates an instrument that measures sulphur metabolites in plasma.

“It occurs at higher rates in communities which are isolated. If there’s a mutation in the community, and the population is isolated, it gets propagated more often,” said Majtan, who came to CU as a postdoc in 2007.

“All the milestones related to homocystinuria have been achieved in the Kraus Lab,” Majtan said. “In Dr. Kraus, we have a world-class expert working on this disease.”

Before the enzyme therapy was developed by the Kraus Lab, leading to the current first-in-human interventional clinical trial, the lab found the “holy grail.” Five years ago, Kraus and Majtan, together with their collaborator Alfonso Martínez de la Cruz, PhD, discovered the crystallographic structures of the enzyme in basal and activated forms. The finding allowed the researchers to understand why and how mutations in the enzyme cause the disease.

Hopeful for ‘whatever the potential is’

Maestas is excited to take part in a trial that could, at long last, bring a cure to his lifelong disease. “I’m hopeful for whatever the potential is,” he said. “Even if it doesn’t work, at least we’ve closed one door and maybe it leads to another door to be opened.”

Calling himself a “stubborn and strong-willed patient,” Maestas has pushed to get to the point where his doctors would allow him to eat a hamburger. He still limits his protein intake, but Maestas occasionally enjoys a filet mignon or chicken breast. “Until three years ago, I would never have known what a steak tastes like, or how much I don’t like fish.”

The disease is caused by low levels of the enzyme cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS), which results in increased levels of both homocysteine and methionine, the latter being an amino acid found in nearly all foods.

NEWBORN SCREENING

There was a period of time, not long after Russell Maestas was born in 1993, when the state of Colorado stopped screening for homocystinuria at birth, mostly due to the inaccuracy of the testing and the fact that it missed cases. About 10 years ago, improvements to technology spurred the resumption of the tests as part of comprehensive newborn screening.

Unfortunately, newborn screening for homocystinuria is still not sensitive enough, and therefore many patients are still missed and only diagnosed later in life.

“When the enzyme replacement therapy successfully passes through the clinical trials – and we are optimistic this will occur – it will become even more relevant to identify patients and treat them with the available therapy as soon as possible,” said Tomas Majtan, PhD, a leading expert in the field of homocystinuria research. “Our experience with the animal models is that early continual treatment completely prevents even the most severe symptoms of the disease.

By identifying the structural information of the enzyme, then learning exactly how the enzyme works, Kraus and Majtan were able to develop an enzyme replacement therapy. Kraus began studying homocystinuria as a postdoctoral fellow at Yale University. “Nothing was known about this disease at the time, so my advisor said, ‘Why don’t you work on homocystinuria and see if you can purify the enzyme,’” he said.

‘Critical unmet need’

Kraus discovered that the gene mutations exist on chromosome 21, and that the enzyme deficiency is chiefly caused by mutations in CBS. “Basically, there’s a critical unmet need for clinical options for these patients,” he said.

Maestas, the only member of his family to have homocystinuria, said he tended to worry more about the disease before his teenage years. “Around the time I was 10 or 12, it caused some anxiety when the doctors explained to me I could have these adverse effects if I didn’t take care of myself,” he said.

He’s felt less apprehensive with age, realizing that he can manage the illness by paying close attention to his diet. “It doesn’t dictate how I live my life.”

The degree to which patients struggle with the disease varies, but some face considerable challenges.

“The strict dietary requirements advised by doctors substantially affects the quality of life of the patients and their families,” said Majtan, who recently attended a homocystinuria patient advocacy groups gathering in Rome. “Based on our pre-clinical data, we are convinced that the enzyme replacement therapy could markedly reduce or entirely eliminate dietary management of the patients, who in turn could enjoy life in full.”