When Valeria Canto-Soler, Ph.D., was a biology student in Argentina, she dreamed of a career studying elephants and other African wildlife in their natural habitat.

But life took her on a different journey. In July, Canto-Soler joined the Department of Ophthalmology and the Gates Center for Regenerative Medicine as the Doni Solich Family Endowed Chair in Ocular Stem Cell Research.

“I like to joke about it,” she says. “Instead of spending my life studying animals in the wilds of Africa, I’m in a dark room sitting in front of a microscope.”

After an international search, Canto-Soler also was named director of CellSight, the Ocular Stem Cell and Regeneration Research Program, in partnership with the Gates Center and the Department of Ophthalmology. She also will be an Associate Professor of Ophthalmology at the CU Anschutz School of Medicine.

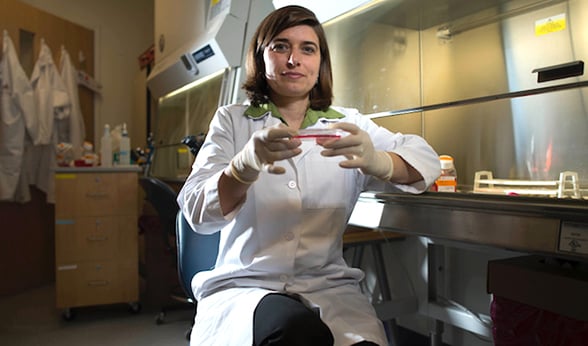

Valeria Canto-Soler, PhD, at work growing mini retinas in a petri dish.

Valeria Canto-Soler, PhD, at work growing mini retinas in a petri dish.

This $10 million ocular stem cell and regeneration program initiative began when the Gates Center helped facilitate a $5 million matching grant from the Gates Frontiers Fund to research the potential for stem cells to treat age-related macular degeneration, the leading cause of blindness in people ages 50 and older.

The Gates Center and the Gates Biomanufacturing Facility partner with the CU Anschutz Medical Campus and center members on leading-edge work in stem cell biology and regenerative medicine, accelerating discoveries from the lab toward clinical trials as well as cures and therapies for patients.

“I dreamed of launching a stem cell research program like this for years,” she says. “The leadership at both the Gates Center and the Department of Ophthalmology has the same vision that I have. Working together, we can make it happen.”

Growing up in Argentina

Canto-Soler grew up in Mendoza, Argentina, a city on the eastern side of the Andes Mountains. Similar to Denver in that it’s nestled in the foothills, Mendoza’s close proximity to the mountains gave her the opportunity to hike, explore and marvel at the natural wildlife she encountered.

But when it came to a career choice, it was more difficult for her to decide how to direct her love of nature and biology. In contrast to the U.S., students in Argentina have to decide on a career early.

“It’s a very important decision and there are very few chances for you to change your mind after that,” she says.

As a young biology student, Canto-Soler found herself drawn to the study of the human nervous system and how the sense organs work.

“Year by year, I felt more and more fascinated by the biology of the human body,” she says. “In the last two years of biology school, I started to work in a lab studying the nervous system. That defined my future.”

Canto-Soler earned a B.S. in Biology from the University of Cordoba School of Natural Sciences, Cordoba, Argentina in 1996. In 2002, she completed a Ph.D. in Biomedical Sciences at the Austral University School of Medicine in Buenos Aires.

A Johns Hopkins Fellowship

After she earned her Ph.D., Canto-Soler had the opportunity to explore new vistas. She was accepted as a Fellow with the Retinal Degenerations Research Center in the Department of Ophthalmology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. She worked with renowned scientist Ruben Adler, MD, at the Wilmer Eye Institute.

“I was so excited – the focus of his research was the development of the eye,” Canto-Soler says. “It was perfect for me.”

She thought her fellowship would provide her the knowledge and experience she could take back to Argentina, but she found new challenges to keep her in the U.S. When her mentor, Dr. Adler, died in 2007, she took over his role at Wilmer to continue their work.

A New Discovery

In 2014, Canto-Soler and her team created a miniature human retina in a petri dish, using human stem cells. The mini retinas had functioning photoreceptor cells capable of sensing light. This cutting-edge research opened up the potential to take cells from a patient who suffers from a particular retinal disease, such as macular degeneration, and use them to generate mini retinas that would recapitulate the disease of the patient; this allows studying the disease on a human context directly, rather than depending on animal models.

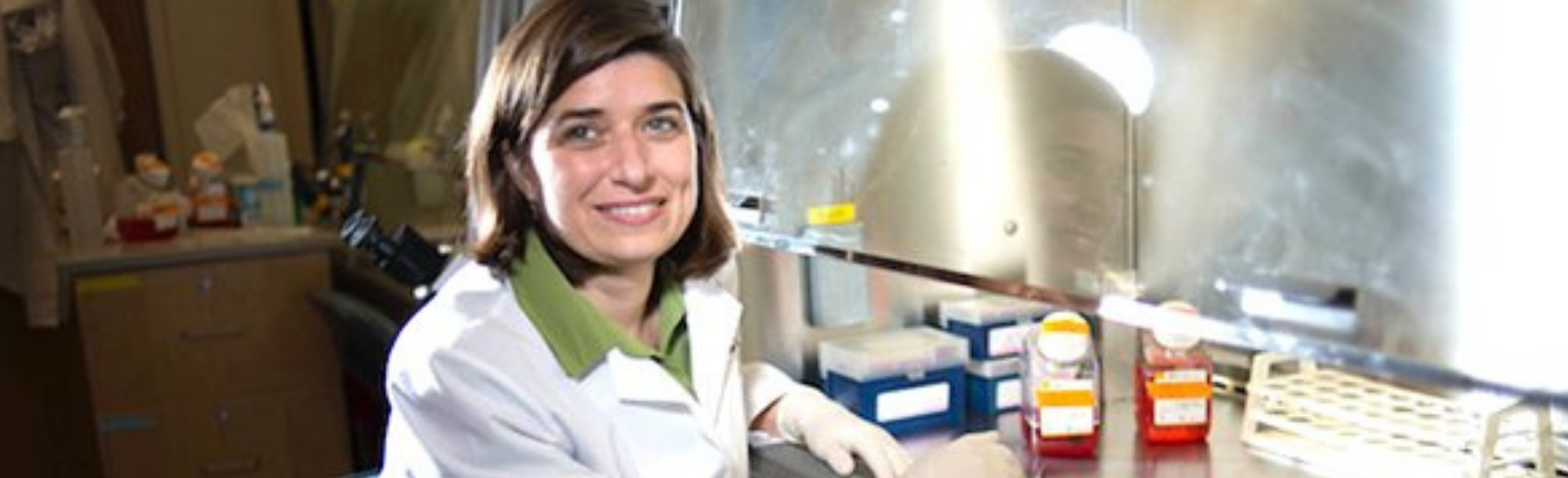

Valeria Canto-Soler, Ph.D., hopes her research will someday result in cell-based treatments for patients suffering from vision loss.

Valeria Canto-Soler, Ph.D., hopes her research will someday result in cell-based treatments for patients suffering from vision loss.

This research could lead to personalized medicine and drug treatments for specific patient needs. At CellSight, Canto-Soler will work with clinicians and members of the Gates Center to create patient registries and cell banking. She hopes her research will someday result in cell-based treatments; retinal patches, for example, which could be transplanted into a patient’s eye, possibly curing blindness.

“Once you transplant a retinal patch, the cells have to establish all the right connections with the patient’s own retinal cells in order to process the information and produce a visual image,” she says. “No one really knows how to do that yet.”

But she’s confident the clinicians from the Department of Ophthalmology, and the researchers at CellSight and the Gates Center, will work together to make the dream a reality.

“I’m definitely a dreamer,” Canto-Soler says. “I never imagined we could generate human mini retinas in a petri dish. And to see that happen made me a believer. I believe our scientific dreams can come true if we pursue them in the right way.”

The letters and emails she receives from those who have family members or friends suffering from sight problems or blindness inspire her. They’re also looking for answers.

“It’s what gets me motivated to come to work every day,” she says. “I’m excited to think about how we could help people and the impact that would make in their lives.”

_BANNER.jpg)