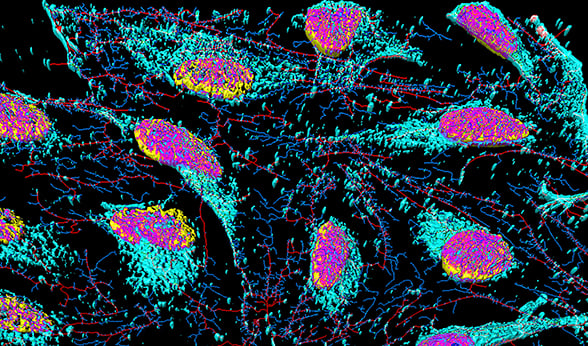

Her cells, nicknamed HeLa cells, changed medicine’s path. They became the most-commonly used cancer cell line in biological research history, making profound contributions to science and saving countless lives. Years after the poor Black woman unknowingly provided those cells to scientists, her story emerged, shining light on patient rights.

Today, as Henrietta Lacks’ tale recaptures the public eye, David Kroll, PhD, a professor in the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, watches the headlines with more curiosity than most. Last month – days after some family members filed a lawsuit against a biomedical supply commercial giant claiming a right to profits the family never received – the dedicated mother who grew up farming the tobacco fields of Virginia was honored by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The headlines bring mixed emotions to Kroll, who became entwined in the Lacks’ family story when he read an article in the New York Times Magazine 15 years ago. Written by a then-little-known science journalist named Rebecca Skloot, the article detailed what happened to patients’ tissue when it was taken at a hospital. It questioned who owned the cells when they became valuable.

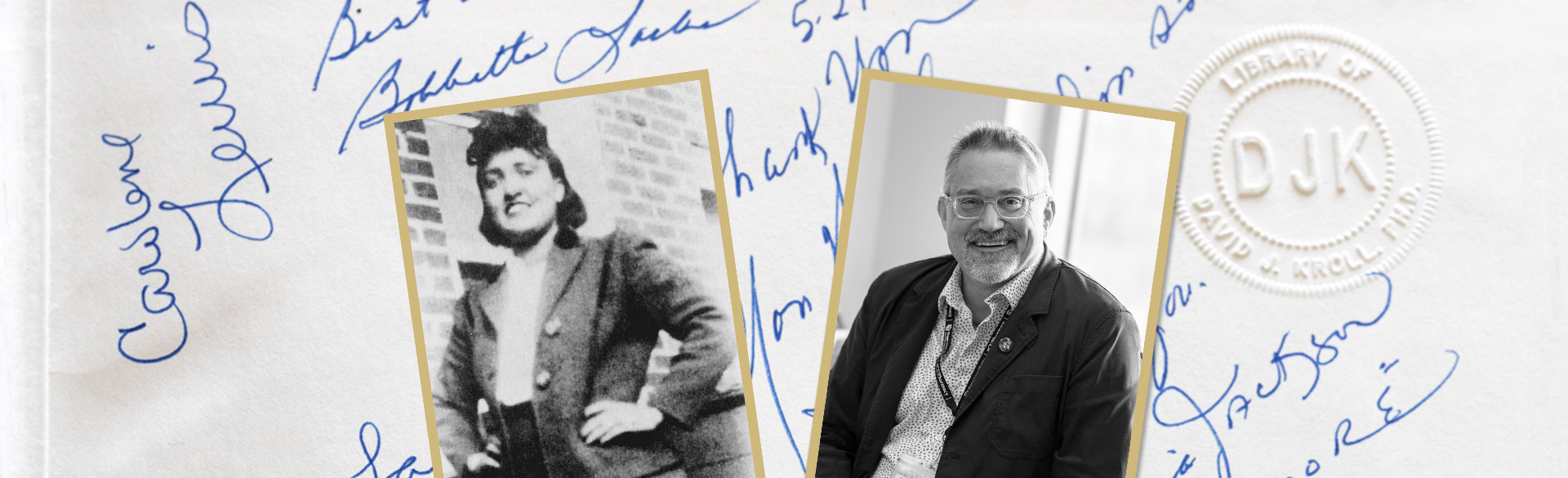

Pharmacy Professor David Kroll, PhD. Pharmacy Professor David Kroll, PhD.

|

“Then, in tiny, tiny print at the bottom, it said she’s working on a book on the cancer cells that came from Henrietta Lacks,” said Kroll, now the director of the School of Pharmacy’s Master’s Degree and Certificate Programs at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. So, he emailed Skloot.

Making ‘use of this gift that this woman had given’

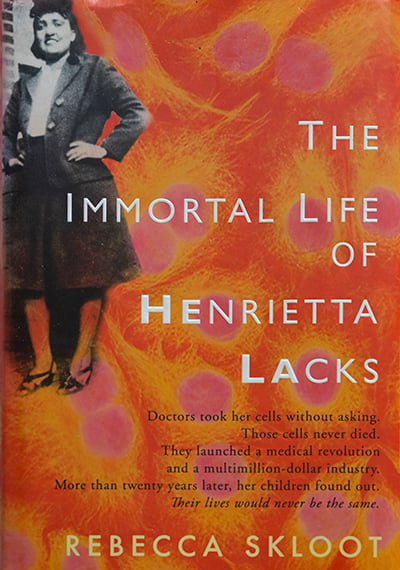

“I sort of felt like the life I had, and that I have today, was partly due to the fact that I had made use of this gift that this woman had given in 1951 that actually caused the end of her life,” Kroll said, explaining why that email led to a working relationship with Skloot, numerous articles of his own on “the ethical conundrum” Lacks’ story unfolded, and the title of scientific adviser for Skloot’s New York Times best-selling book, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.”

HeLa cells were significant in Kroll’s graduate work and dissertation on how a certain cancer enzyme was regulated, although he didn’t know the full story behind them at the time.

While her cells were a “gift” to science, they were taken without consent when she was treated for cervical cancer at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Diagnosed eight months before her death on Oct. 4, 1951, Lacks endured a brutal – but then advanced – treatment regimen in the “colored ward” of the nonprofit hospital.

Rebecca Skloot with fellow foundation members David Kroll and Blair LM Kelley. |

“She was fortunate in one sense,” Kroll said of Lacks, whose doctors used radium tubes inside her cervix that burned her brown skin black. “Although they did have a segregated cancer ward at Hopkins, Black people got to see the same doctors that the white people got to see,” which was not true at other hospitals at the time.

‘There’s almost a motherly quality to them’

But Lacks’ case came during an era when conducting research on Black patients was looked at by some scientists as their due for care, and consent laws were nonexistent. George Gey, MD, then a doctor at Johns Hopkins who had been struggling for years to find human cells he could reproduce in the lab, cultured some of Lacks’ cells. The results were astounding.

“They were the first human cancer cell line that was isolated and continually carried in culture,” Kroll said of Lacks’ unusually aggressive cancer cells that were so hardy and forgiving, they are now commonly used in teaching labs, where even inexperienced students can’t kill them.

Speaking at a ceremony in 2010, when Lacks’ unmarked grave finally received a donated headstone, Kroll told her gathered family members in an impromptu talk how the characteristics of her cancer cells that made them so deadly were what made them special to science.

“They are so forgiving,” he told her children and grandchildren, “there’s almost a motherly quality to them. The cells can tolerate a lot of mistreatment and still survive in culture. They can survive the sloppy, careless technique of high school students or college students, and that sort of caretaking led to the teaching of the next generation of scientists.”

Cells provide 55 million tons; support 116,000 studies

The cells were so robust, they doubled every 24 hours. When presenting one of Lacks’ sons with the Director-General’s Award last month, the WHO director noted that at least 55 million tons of the prolific HeLa cells have been distributed worldwide, contributing to 116,000-plus studies, many of them ground-breaking.

The cells led to cancer therapies, Jonas Salk’s life-saving polio vaccine and preventive AIDS drugs through the isolation of HIV. They launched the genomics revolution, went to space for zero-gravity studies and were integral in two Nobel prizes.

HeLa cells. HeLa cells.

|

“German scientist Harald zur Hausen won the Nobel prize for the demonstration that human papilloma virus can cause cervical cancer,” Kroll said. “He used her cells in some of that prize-winning work. It turned out that Henrietta Lacks was infected with HPV through her husband, who unfortunately slept around a lot.”

No company profits made off the instrumental cells ever went back to the Lacks family. And consent was never requested from her family members for decades after Henrietta Lacks’ death, with her name and medical records being publicly distributed and her cell genome even published online.

Bringing injustices to public attention

Lacks’ story also has taken on renewed life recently with the emergence of the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement – two events that reignited equity issues her story has long narrated.

“Initially, the popularity of the book raised attention of both the general public and the medical community to injustices that medicine has inflicted on the African American community,” Kroll said. Then Oprah’s production company filmed a movie based on the book. “And anytime Oprah touches anything, it turns to gold.”

The cells led to cancer therapies, Jonas Salk’s life-saving polio vaccine and preventive AIDS drugs through the isolation of HIV. They launched the genomics revolution, went to space for zero-gravity studies and were integral in two Nobel prizes.

Through her own perseverance and passion – evident in her 10 years of research with the family that was quite unwelcoming at first – Skloot has raised awareness through 11 years of speaking at medical campuses around the world, Kroll said.

“She talks about the story and teaches medical students in particular, but also young PhD students, about the responsibilities that we have when we use a laboratory reagent that was somebody’s tissue –that came from a real human being.”

Fulfilling a promise to Deborah Lacks

The BLM movement really bumped attention, evidenced by increased donations to Skloot’s Henrietta Lacks Foundation, Kroll said. While working over the years with the family, Skloot formed a strong bond with Deborah Lacks, Henrietta Lacks’ daughter and the family member most responsible for allowing Skloot’s research.

“They are so forgiving, there’s almost a motherly quality to them. The cells can tolerate a lot of mistreatment and still survive in culture. They can survive the sloppy, careless technique of high school students or college students, and that sort of caretaking led to the teaching of the next generation of scientists.” – David Kroll, PhD, on HeLa cells

Skloot promised Deborah Lacks, who died just nine months before the book was released, “crushing Rebecca,” Kroll said, that she would give back to the family in some way once the book published.

Subsequently, Skloot launched the foundation with the book’s profits, with Kroll as a founding member. Today, Kroll reviews grants and counsels Lacks’ progeny, largely on educational prospects, sending many descendants to trade schools and colleges.

Book cover |

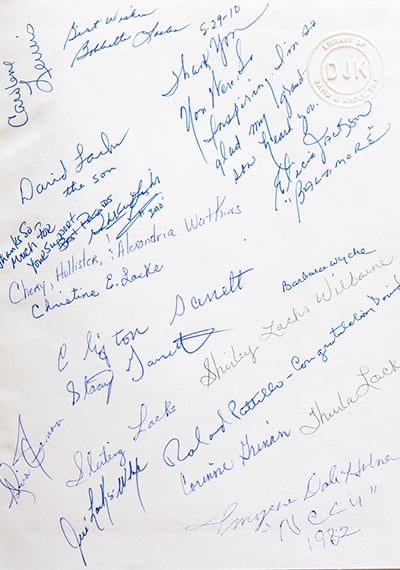

Signatures on dissertation |

“The foundation operated for the first 10 years on Rebecca’s profits from the book, the movie profits and private donations of 2 bucks, 5 bucks, 500 bucks,” Kroll said. Now, donations are slowly building, he said.

Awareness forms steppingstone to equality

The increased awareness of the HeLa cells’ contributions is rewarding, Kroll said, acknowledging last month’s WHO award. The Lacks family members, let alone the public, didn’t even know about the use of their matriarch’s cells until 22 years after her death at age 31.

Henrietta Lacks’ story has been one steppingstone toward the equality Kroll envisions. And it has been responsible for regulatory changes supporting patients, such as the Belmont Report’s rules of informed consent.

“If you are enrolled in a medical study, you have to be told the risks and benefits,” Kroll said of the Belmont Report, largely inspired by the Tuskegee Syphilis Study that purposely left Black men with syphilis unknowingly untreated. “Patients still sign off on their rights to their tissue once it’s taken out of their body, but at least it is anonymized now.”

While there’s still “a long way to go,” Kroll wants to see all traditionally underrepresented groups treated equally in all aspects of science and healthcare. With his dissertation tucked in his desk drawer now signed by many grateful Lacks family members, he can rest at night knowing he’s helped. “It’s just really touching to be part of this all.”

Did you know?

Geneticist Theodore Puck, recruited by the University of Colorado School of Medicine in 1948 to establish the department of biophysics, successfully cloned HeLa cell strains in 1955, as referenced in Rebecca Skloot’s award-winning book. As his trainees became professors in Denver and Boulder, Colorado became the center for understanding the minimal nutritional requirements for cell growth.

Puck, a pioneer of somatic cell genetics and single-cell plating, is also the namesake of “Theo,” a new, luxury apartment building on the old Ninth Avenue and Colorado Boulevard campus site. The complex is described in advertisements, using Puck’s trademark bow tie fashioned into a DNA helix, as “A place with good genes.”

.png)

.jpg)