Cell and gene therapies (CGTs) are poised to transform the practice of medicine, but further advancement will require close partnerships between academic institutions and biotechnology companies, Terry Fry, MD, executive director of the Gates Institute, told a standing-room-only crowd in the Torreys Peak Auditorium of Bioscience 3 on March 1.

Fry, the inaugural director of the Gates Institute, delivered the keynote address at the Colorado Bioscience Association’s “Biotech Symposium: Innovations in Cell + Gene Therapy.” The event was the CBSA’s first symposium focused specifically on cell and gene therapy, indicating a growing interest in CGTs.

“The scientists at (the University of Colorado) Anschutz Medical Campus really are brilliant in their ability to develop these ideas, but few faculty have the expertise in dealing with the regulatory and manufacturing complexity required to commercialize the therapies and ultimately deliver cures to patients,” said Fry, who is also a clinical professor of pediatric oncology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

The symposium was held at the Fitzsimons Innovation Community campus, just steps away from the Gates Biomanufacturing Facility (GBF) in Bioscience 1. GBF provides state-of-the-art manufacturing capabilities and is an integral part of the Gates Institute.

Building powerful partnerships in the field

The Gates Institute is designed to fill gaps in traditional academic infrastructure, from providing internal resources to strengthening industry partnerships. These efforts will “put CU Anschutz on the map in the field of cell and gene therapy,” Fry said.

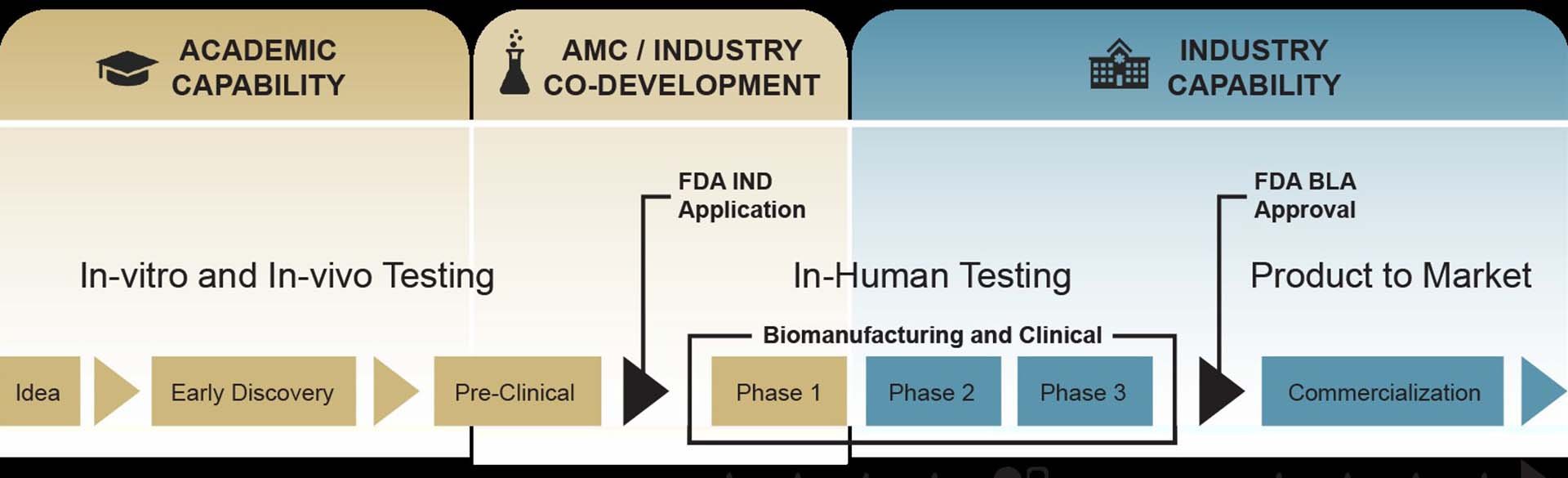

He described the steps in a CGT product’s lifecycle, beginning with early discovery and proof of principle, where academia excels, to pre-clinical testing and investigational new drug applications, where industry partnerships become paramount. A diverse group of individuals – clinicians, doctors, researchers, regulatory experts, and a facility compliant with the Food & Drug Administration’s Good Manufacturing Practices – are key to the effort.

Fry is a pioneer in chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR T) cell therapies, a form of CGT that starts by removing immune cells known as T cells from a patient’s body through a blood draw. The cells are then engineered to target specific molecules on cancer cells and returned to the patient’s bloodstream.

Making the campus a research leader

Fry noted that the first CAR T-cell therapy was approved by the FDA in 2017 for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Although many cancer patients initially experienced remission, the majority have since relapsed, indicating need for additional research. The ability of GBF to move translational research forward has enabled CU Anschutz to join leaders in the field through development and launch several internal CAR T-cell trials on campus, seeking to address issues with early CAR T therapies.

One problem that arises with CAR T therapy, Fry told the attendees, is that the engineered immune cells often aren’t able to target tumor cells with low levels of the target molecule, and studies are underway to learn why.

There are currently three CAR T studies ongoing at CU Anschutz: a phase I study in adults with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma that opened at UCHealth in 2020; a phase I/II study of pediatric patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomata that opened at Children’s Hospital Colorado in 2021; and a first-in-human phase I/Ib study of adolescent and adults with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma that opened at UCHealth in 2022.

Getting drug discoveries into the clinic

Fry invited GBF Director Matthew Seefeldt, PhD, to expand on the ability of the GBF to navigate what’s known in the scientific community as the “valley of death” in translational research.

“Principal investigators by definition are very creative,” Seefeldt said. “They can come up with a lot of ideas, but they don’t necessarily have those blocking and tackling elements needed to get a drug into the clinic. That’s where we come in, to handle the hard problems and help in that early stage to get research into phase I clinical trials.”

The GBF currently has 10 investigational new drug applications in process, some for external clients, Seefeldt says. The work with industry has enabled the facility to build its infrastructure while strengthening its ability to serve campus researchers.

.png)

.jpg)