Sometimes life takes unexpected turns and puts you on a path you could never foresee. That was true for Donald “Don” Egan, MD ’66 (Resident ’70). His first career started in 1958 with the U.S. Air Force Academy, where he quickly learned he would not be suitable as the next Maverick.

“They put me in a jet fighter plane, and I realized that I had to do something other than that for a career,” he joked.

Late in his senior year at the Academy, Egan expressed interest in medical school and looked into classes at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Classes were full, but the dean at the time said that if Egan could complete eight hours of organic chemistry and four hours of biology, he could be admitted.

|

Did you know? Dedicated to improving lives through prevention, education and treatment, Addiction Research and Treatment Services is on the leading edge of treatment services. In fiscal 2020-21, ARTS treated nearly 1,800 individuals among its nine treatment programs. ARTS offers medication-assisted treatment for opioid- and alcohol-use disorder and specialized treatment services for individuals involved in the criminal justice system, HIV positive individuals and women. |

This pivotal moment launched Egan down a career-long path of pioneering medication-assisted treatments and programs for people suffering from addiction. He created Addiction Research and Treatment Services (ARTS) at the CU School of Medicine and led other innovative efforts that gave people battling substance issues “some semblance of a normal life.”

With his newfound dream, the young cadet spent the next six months taking night classes and became the first Air Force Academy graduate to be assigned directly to medical school upon graduation. Egan went on to graduate from the CU School of Medicine in 1966 and began his residency at the University of Colorado Hospital (previously Denver General Hospital), now UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital.

A fateful night

One evening in 1971, a desperate and frightened woman came into the hospital’s emergency room looking for help to get methadone to manage her addiction. Egan, the resident on-call, learned that the woman had been in a New York research program studying methadone as an addiction therapy. Having witnessed his own parents’ struggles with alcohol, Egan was especially sensitive to the woman’s predicament.

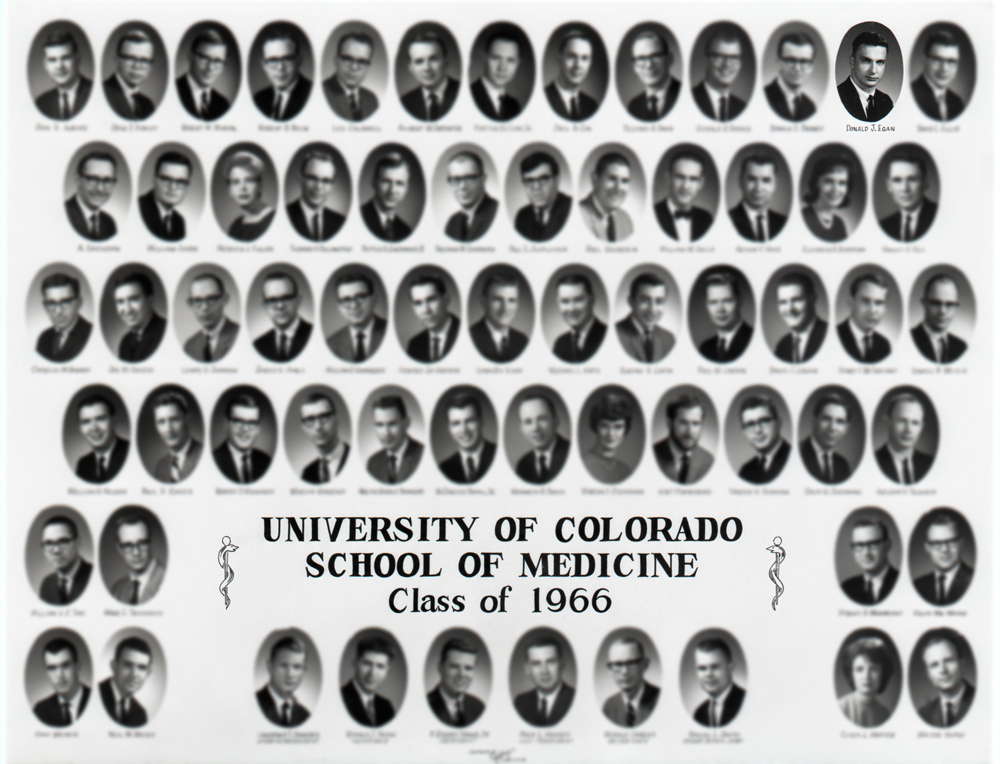

Donald Egan, top right, in the CU School of Medicine’s Class of 1966 photo. |

“At that time, the law said you could treat someone in withdrawal, but you could not give them opiates/opioids on any kind of a maintenance basis,” he said. “In other words, you could reduce the difficulty with withdrawal with a few days of medication, but beyond that it was illegal.”

Later, unable to shake the thought of the woman who needed help, Egan discovered the work of a trio of researchers at The Rockefeller University Vincent Dole, MD, and Marie Nyswander, MD, and Mary Jeanne Kreek, MD. Kreek had developed a methadone treatment for heroin dependence and the three them found that the drug relieved cravings and prevented withdrawal symptoms in opioid users.

The findings also showed that methadone didn’t produce the type of euphoria or tolerance people experience while using opioids. Their research was crucial to the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) approval of methadone as an intervention, and eventually as the treatment gold standard, for addiction to opioids, such as heroin and pain relievers.

Egan knew this breakthrough program needed to come to Colorado. He traveled to New York and applied for an exemption to prescribe methadone on a maintenance basis. Empowered after witnessing the program firsthand, Egan launched ARTS in the CU Department of Psychiatry.

The early days

Egan got to know Gerald “Gerry” Starkey, medical coordinator for the City and County of Denver. Starkey was concerned about Colorado’s burgeoning addiction problem.

With $28,000 in support from the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, Starkey and Egan began an innovative community improvement project aimed at providing methadone on an ongoing basis to treat offenders with a history of opioid use.

Egan recalled, “We knew that $28,000 wasn’t going to last long, so we either had to make a go of this or go back to the med school with our hats in our hands and our tails between our legs, and I wasn’t about to do that.”

The project started off slowly because the need for services was great, but staffing was limited. Monitoring participants proved challenging and some participants tampered with their urine samples to remain in the project and others only occasionally visited the office for medication.

Expansion and scrutiny

Despite the challenges, the project grew in reputation, and Egan knew he needed more funding. He applied for funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to use methadone for opioid addiction and relocated the growing project to a larger office in the City Park neighborhood in Denver.

The Veterans Affairs (VA) Administration took interest in Egan’s project, as there was an increasing need to treat opioid addiction among veterans returning from Vietnam. Egan noticed a few empty buildings on the Fort Logan military campus in southwest Denver. He learned that, for a nonprofit organization, the military would rent former officer houses for $200 per month, so he made a deal to rent five houses.

That was the beginning of the ARTS campus at Fort Logan. ARTS still operates substance use treatment programs on the Fort Logan campus, including men’s residential (Peer I) and women’s residential (Haven) programs, as well as an adolescent program (Synergy).

|

U.S. Opioid Crisis – How Did We Get Here?

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

While additional treatment options increased for adults, a growing number of adolescents needed help. Asked by District Attorney Dale Tooley to help Colorado youth, Egan created an adolescent treatment program with a grant for $50,000. He recruited Tom Brewster (future associate professor of psychiatry at CU) from California to expand addiction treatment and programming at Fort Logan.

“We wanted to give folks a chance to return to some semblance of a normal life,” he said. “We wanted them to have a job and have some freedom all while trying to normalize this type of medication-assisted treatment with methadone.”

Egan and his team battled the societal stigma often attached to those in recovery. Many viewed addictions as criminal behavior caused by a lack of self-control.

“This all started off as very controversial,” Egan said. “The care in the city was basically nonexistent at that time, and abstinence-only programs for addiction were widely accepted as the ‘right’ course of action, so they received most of the funding. We were trying something new, so there were people who liked me and people who didn’t.”

Medication-assisted treatment proved far more beneficial and cost effective than jail. The Department of Psychiatry remained a valuable and reliable partner for ARTS because of the understanding that methadone was an effective and necessary treatment for individuals struggling with opioid use disorder.

“I like to think of it this way: If someone has high blood pressure, you don’t punish them or belittle them. You give them blood pressure medication and continue to monitor their progress,” Egan said. “We have to look at medication-assisted treatment for substance use in the same way. It’s a medical issue and not a personal failure.”

Lighting the path forward

Fifty years later, ARTS continues to serve as a beacon of hope for those who have severe and chronic substance use disorders. Egan and others who had the courage to forge a new path in personalized medicine created the momentum to keep pushing forward. Inspiring others to take a chance, he started a positive ripple effect that allowed Brewster, Tom Crowley, MD, and others to turn ARTS into one of the largest substance use treatment programs in Colorado today.

“It’s amazing to see the growth of the operation and that so many people who came through our doors wanted to get well,” Egan said. For people in recovery, “they now have a community of peers they can relate to because they’re all going through the same thing together.

“Looking back, that was one of the happiest times in my life,” he said. “Other than having my own children, it was the most important and gratifying thing I’ve ever done. And I’ve done a lot.”