In the end, his patient died. But as Ajay Major, MD, MBA, then an intern, flipped through the old veteran’s medical record, he found comfort in the memories the notes inspired.

Now Major, a second-year internal-medicine resident on the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, calls up those memories of the witty old man with terminal cancer who always asked for bourbon (and his devoted wife who always rolled her eyes in response) as a continual reminder of the importance of compassion in health care.

“Medicine is hard,” Major said. “We see a lot of patients with a lot of difficult medical issues, and I think burnout stems not just from feeling overworked, but also from feeling that we’re not truly caring for our patients on a human level.”

Major, co-president of the CU Anschutz School of Medicine (SOM) Resident Chapter of the Gold Humanism Honor Society, spread his message during the society’s annual Solidarity Week Feb. 12-16 by encouraging his colleagues to take part in the week’s centerpiece program, Tell Me More (TMM).

Changing the conversation

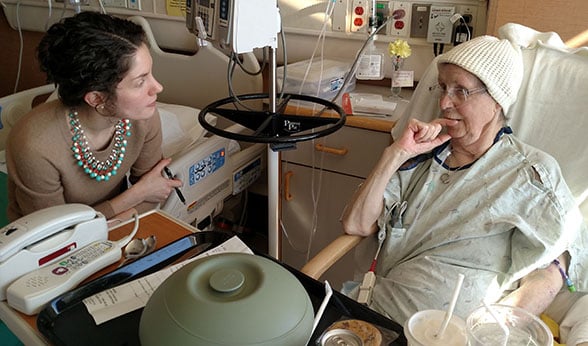

Megan Griff, MD, chats with University of Colorado Hospital patient Frances Cory as part of a program aimed at teaching the value of compassion in medicine.

Megan Griff, MD, chats with University of Colorado Hospital patient Frances Cory as part of a program aimed at teaching the value of compassion in medicine.

Armed with a TMM questionnaire and a smile, second-year internal-medicine resident Megan Griff, MD, entered her patient’s room, finding Betty Redwine, 77, wrapped in a light blanket and relaxing in a chair. “Is it OK to talk and find out about your life?” Griff asked, after explaining the program and introducing Major and attending physician, Jeannette Guerrasio, MD.

“OK,” Betty Redwine said, returning her doctor’s smile. “But it’s nothing exciting,” she said, grinning up from beneath a black-suede, shower-like cap she informed her guests was taming her unruly hair.

Prompted by four TMM questions, Redwine soon was sharing pieces of her past. Topics of capillaries and high blood pressure gave way to children’s feats and life’s treasures, sounding more like tea-time chatter than hospital-room discussion. When Redwine let a little secret slip, the room exploded in utterances of disbelief.

“What?” Guerrasio said, after Redwine revealed she worked as a registered nurse for 35 years. “Why didn’t you tell us?” asked Griff. “My mom is a nurse, too,” Griff said, when the commotion subsided. “You guys are hard-workers,” she said, patting Redwine’s hand.

Staying centered on the cause

While it might seem miniscule, a small dose of compassion can result in an array of benefits, Major said. “It allows the patient to feel that the care team really cares about them, but it also brings some catharsis for providers. Just finding out a little bit more about our patients’ lives outside of the hospital can help re-center us in the work that we are doing as physicians and, I believe, help prevent burnout.”

On the patient side, studies show compassionate healthcare results in higher patient satisfaction, a higher pain threshold, reduced anxiety and better outcomes, according to the Gold Foundation, which cites supporting studies on its website.

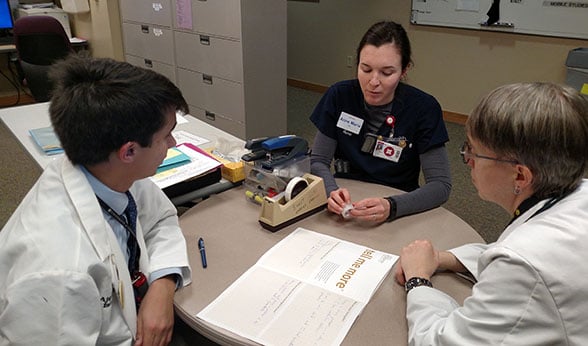

Ajay Major, MD, MBA, left, and Jeannette Guerrasio, MD, right, talk with Anne Marie Fleming, RN, about the Tell Me More program.

Ajay Major, MD, MBA, left, and Jeannette Guerrasio, MD, right, talk with Anne Marie Fleming, RN, about the Tell Me More program.

“People develop diseases for lots of reasons, and everyone’s lives really affect the way they respond to health problems,” said SOM Chair of Medicine David Schwartz, MD. It makes sense that trusted patient-provider relationships result in better care, he said. “We need to know how their lives might be contributing to the development of disease, and how their lives might contribute to our ability to effectively treat their disease,” he said.

Remembering: ‘I’m a person’

Looking up from her bed as the TMM trio walked into her room, Frances Cory, 79, had them laughing before even agreeing to chat. “You want to talk beyond my medical condition? You mean you don’t care about my medical condition anymore?” said the mother and grandmother, who later responded to a question about her biggest strength: “My sense of humor.”

Cory, who shared with her visitors that she had served more than 5,000 volunteer hospital hours during her lifetime, said she thought the program was important. “It’s nice to know that you take the time to talk to your patients. I’m a person.”

The TMM program offers a valuable reminder for medical students that their patients are people, and not just medical mysteries to solve, Guerrasio said. “I actually, as a doctor, find these conversations really helpful. And it’s what makes me come to work every day.”

Notes about the patient-doctor chat are jotted down on the TMM questionnaire, which is then displayed on the wall so that everyone involved in that patient’s stay, from therapists and nurses to doctors and janitors, can use it as conversation fodder, Major said.

[perfectpullquote align="right" bordertop="false" cite="" link="" color="" class="" size=""] ‘The more passionate individuals are about their profession, and the more they enjoy what they are doing, the more engaged they become. These things feed on each other in very positive ways.’ ̶ David Schwartz, SOM Chair of Medicine [/perfectpullquote]

Seeing nothing as too small

By getting to know his end-stage cancer patient and his wife as an intern, Major learned not just about his patient’s bourbon routine, but that he was a strong war veteran who had “always been a fighter.” That helped Major, when the man opted for a late chemo-treatment that was questionable at his stage and age. While the patient fared well through therapy, he developed an infection afterward that ended his fight.

When his patient was transferred to hospice, Major told his palliative caregivers about the bourbon. As he looked through his patient’s medical record after learning of his death, Major was jolted by one caretaker directive: Bourbon, one ounce at bed time as needed.

“It seems like such a small detail,” said Major, who published an article in JAMA Oncology about the patient experience. “But when his fighting wasn’t working anymore, he started thinking about things he really enjoyed in life. And having his little bit of bourbon was kind of important to him. So we made sure he could have that to the end.”