Editor’s Note: The joint efforts of the Gates Institute, Children's Hospital Colorado, and the University of Colorado School of Medicine elevate the research, innovation and care for Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), a collection of difficult-to-treat and debilitating connective tissue disorders. Below, patient Calla Winchell shares how the collaborative effort she found at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus changed her path.

When you have a rare disease, you quickly learn that doctors who understand you are nearly as rare. Since my diagnosis at age 19, I’ve had physicians blatantly look up Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) in front of me. When they misspelled it, it didn’t exactly inspire confidence.

While getting a diagnosis had been difficult, that struggle didn’t end once I had an answer for why my body seemingly worked differently than others. In the post-diagnosis years, I realized the painful lesson that there was no one who could or would manage my health, other than me.

In the first years, there was no guidance at all. Rheumatologists in Chicago, where I attended graduate school, would flat out refuse to see EDS patients, citing our complexity (a complexity I was even less qualified to manage). Unbelievably, it was up to me to research and pore over scientific publications I could barely understand and to try to get my head around the implications of this condition.

Rare Disease Day event explores vision of campus as a regional hub.

In addition to lacking treatments, EDS also struggles to be pigeonholed into a single medical discipline, leaving it mostly to be managed and coordinated by the patients themselves. Collagen is one of the underlying building blocks of soft tissue, so when your body cannot produce it correctly as with EDS, you end up with structurally weak tissue. That is what makes EDS so tricky: It straddles many different bodily symptoms and can express itself in a stunningly wide array of symptoms from constant nausea, easy and often joint dislocation, nerve pain, dizziness, poor vision, headaches and on and on. No two patients will present the same, in severity or symptom.

You send the cancer patient to the oncologist, the multiple sclerosis patient to the neurologist. But where do you send us? There is no single specialist. For that reason, EDS is best managed in a collaborative model, with specialists coordinating care.

Finding a healthcare home

The Special Care Clinic at Children’s Hospital Colorado addressed this lack of home for us and took the burden of management off me. Before I even met the physicians, there were forms to fill out that asked specific questions about the condition that I’d never been asked before. They asked the right questions out of the gate, and my experience got only better. I left the first appointment with the strangest feeling: What if my time as an ignorant expert on my own condition was finished? What if actual experts would guide me, better and more efficiently than my own bumbling?

Calla Winchell participates in rare disease research on campus. |

Over the next few months, that question was answered. Yes, there were people there who knew more than me. What a relief! Accessing appropriate medical care had been difficult for me in Illinois and with my condition deteriorating, I needed more support than ever. So, I moved to Denver from Chicago because I was so sick.

The home I have found at CU Anschutz and the Children’s Hospital’s Special Care Clinic has turned things around for me. I’m feeling better than I did half a decade ago, thanks to a combination of many things: adequate pain management, treatment of underlying comorbidities, the right medication for my dysfunctional stomach, and an EDS-aware physical therapist.

Symptomatic treatment of EDS has also improved, with more understanding of the constellation of comorbidities that can appear in an EDS patient; it turns out, many of us are Venn diagrams of several different, overlapping conditions, and that treating them all can significantly alleviate symptoms.

To me, creations of centers like the Special Care Clinic are a testament to the progress made in recognizing and managing EDS. The concept is simple: all your specialists in one place, on one day. If I’m having an increase in stomach pain, my pain management doctor might pull one of the GI docs in to consult on which medication might be preferable. This clinical model is what I credit with the progress I’ve made with the condition; the team of experts there, headed up by Ellen Elias, MD, make a compelling case for this collaborative organization of clinics to be applied to the management of EDS generally.

Finding hope in innovation

Meanwhile, a parallel team of experts has been working beyond symptom management at the Gates Institute. EDS has no true therapies; Dennis Roop, PhD, and Ganna Bilousova, PhD, co-directors of the Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Center of Excellence research program, aim to change that. Then, after therapy, the much desired, much contested “c” word looms: cure. For a 19-year-old who, post-diagnosis, envisioned her life as slow but inexorable degeneration, that word stirs wild hope and trepidation. Being able to see that research take off, to actually meet the bright minds at work on this problem, has been healing for me, in a less literal and more emotional way.

There is much promise in the future treatment of EDS, as I learn in every research update. There are new methods of discovery to try or a new class of drugs that might slow degeneration of collagen. As a result, the sense of boundary expansion is exciting.

There are many unknowns. It reminds me of a map of Antarctica I bought from an antique store that was old enough that there were huge swathes of white, unexplored and unmapped regions. I was charmed by that representation of the unknown. The area of research with EDS that we are working on feels similar: It is deeply inspiring and exciting, but a lot feels unmapped and unexplored.

The University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus

Having been sick for a decade now and having dealt with iterations of EDS problems my whole life, I have had little choice but to live up to my occupational title of patient. In 2024, it will be a decade since my own diagnosis. Predictably, my condition has progressed in those years, and for many years I struggled even to get good symptomatic management of the condition. I felt trapped as I felt worse and worse, new systems of the body showing dysfunction, new dislocations of joints that had previously been OK.

Yet in recent years, I am pleased to see a change, a shift, in the awareness and treatment of EDS. I’ve not had a physician need to look the illness up and even non-specialists, like ER doctors, have at least a jolt of recognition of the name. For all these reasons, all these steps forward, I feel a sense of optimism for the next decade of my illness that I could never have predicted. In the next 10 years, I can only hope that every EDS patient (and truly, every patient with any under-recognized condition) is able to feel that same hope and to benefit from the advancement being done, in the clinic and the laboratory.

Guest Contributor: Born and raised in Colorado, Calla Winchell is a writer, researcher and a reader, having earned a bachelor’s degree in English from Johns Hopkins University and a Master of Humanities from the University of Chicago. She is also a friend of the Gates Institute; her grandfather Wagner Schorr, MD, is a member of the Gates Institute Advisory Board.

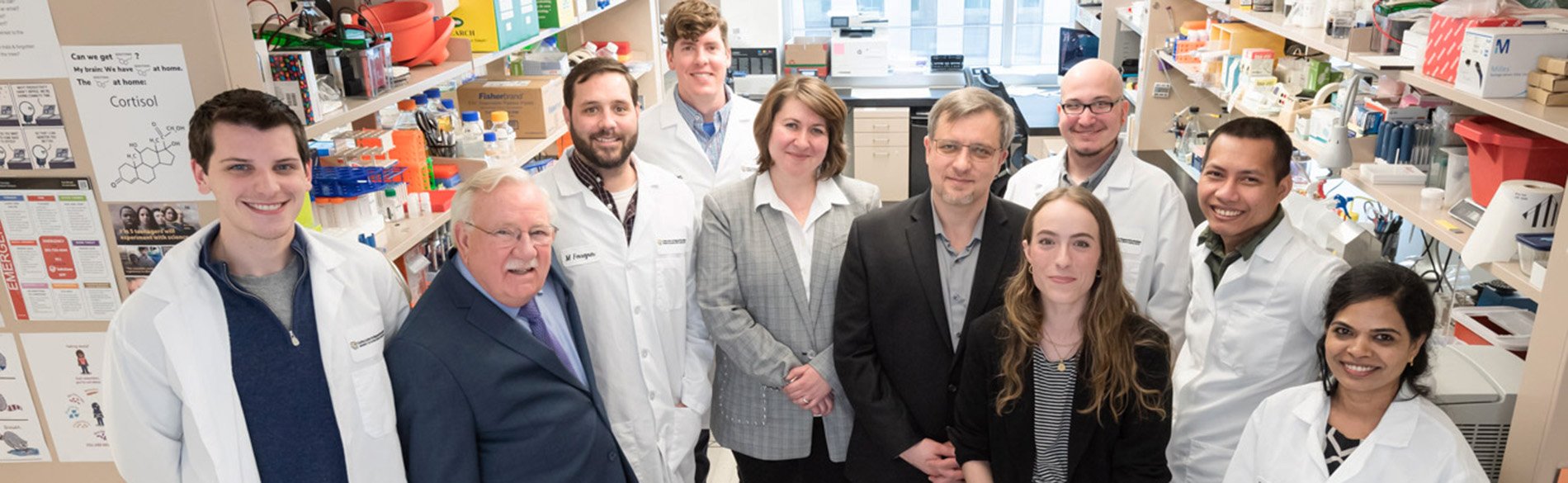

Photo at top: Calla Winchell, front and second from right, poses with members of the Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Center of Excellence research program.