As our bus approached the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum, memories of my childhood flooded back.

I recalled sitting on the floor with my grandfather, Curtis Smith, surrounded by photographs.

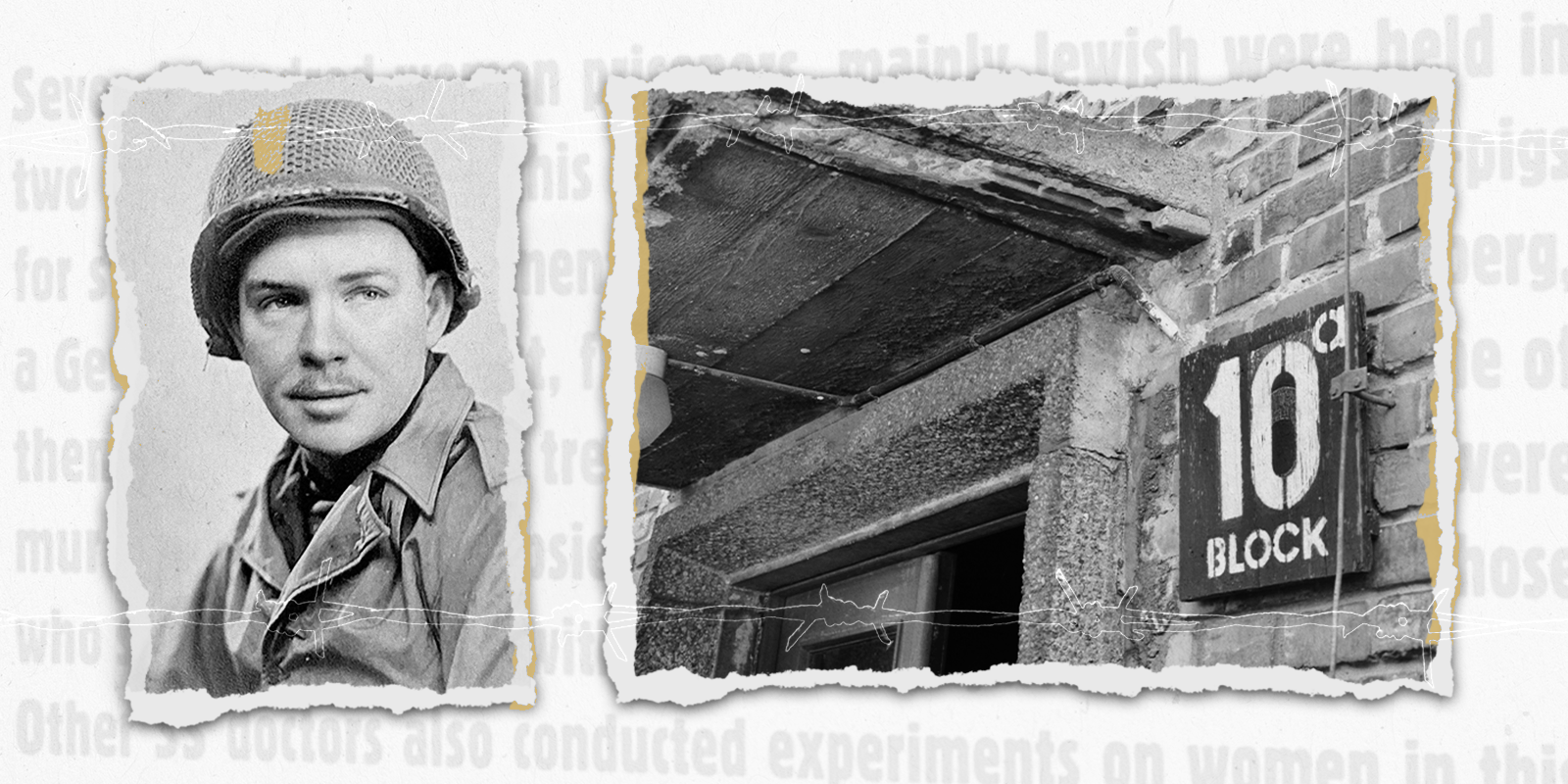

Some showed Jews being led to trains bound for Birkenau, a Nazi death camp that was part of the Auschwitz complex. Others depicted crematoriums inside concentration camps. My grandfather found the photos while serving as a GI in Europe during World War II. His unit had liberated Dachau in April 1945.

Dachau was one of the first and longest running concentration camps in Nazi Germany. Auschwitz was the most efficient. Both had the same goal – rid Europe of Jews and other `undesirables.’

Stories behind each photo

My grandfather, a soft-spoken antiques dealer, would go through every photograph and tell me the story behind each one.

I couldn’t comprehend it then; maybe I could now.

|

Full series: Medicine Behind the Barbed Wire |

It was September and I was covering the “Medical Review Auschwitz: Medicine Behind the Barbed Wire” conference in Poland. Each year the University of Colorado Center for Bioethics and Humanities on the Anschutz Medical Campus sends a small group of fellows to Krakow as part of a program focusing on the role German doctors played in the Holocaust.

My grandfather was no doctor but he and his fellow soldiers saved and treated as many prisoners as they could. They also uncovered gas chambers and mass graves.

Despite the gentleness he showed in his later years-tending his garden and painting landscapes-he talked openly and often about what he witnessed, believing education alone could prevent it from happening again.

“When you walk into something like that it changes you forever,” he told me. “We had seen so much in combat, but nothing prepared us for this horror. Inhumanity on this level was impossible to comprehend.”

Entering the darkness of Block 10

Now, 80 years later, I was standing inside Auschwitz, perhaps the most grotesque monument to `The Final Solution’ still standing.

As I passed under the infamous “Arbeit macht frei” – “Work Sets You Free” sign – I steeled myself for the darkness my grandfather had faced.

The author's personal reflection: Throughout my life I had listened to the stories, watched documentaries and read books about the Holocaust, yet it was here, in this dimly lit basement, that the pain, fear and hopelessness they experienced fully revealed itself to me.

Few places were darker than Block 10. Forbidden to most people, program participants were allowed in. This is where Nazi doctors conducted some of their most heinous experiments on healthy, mostly female, prisoners.

We entered in silence. A wooden operating slab stood in one room. I tried to picture the number of people tortured on that lonely slab. I imagined their fear and terror as they were subjected to inhumane experiments that often killed them.

Yet it is Blocks 5 through 7 that are perhaps the most disturbing. They contain personal belongings of the prisoners and show what they endured daily. Suitcases with names on them, pairs of old shoes. There was a room with piles of human hair, a cruel indignity inflicted on those already robbed of everything.

We often think of the Holocaust in terms of millions. I was now thinking in terms of ones and twos.

Each pair of shoes, every suitcase, the hair – belonged to individuals with names, histories and dreams for the future. For most, it ended here. Of the 1.3 million people sent here, 1.1 million were murdered. Every death, its own small Holocaust.

We walked to the gas chamber and crematorium. They were small, concrete rooms. A simple plaque nearby said, “You are entering the building where the S.S. murdered thousands of people. Please maintain silence here: remember the suffering and show respect for their memory.”

From there we are bused to Birkanau on the other side of the compound. Prisoners were “sorted” within minutes of arrival by medical professionals. Most were immediately gassed. A handful were used as slave laborers, or in cruel medical experiments.

I knelt on the train tracks to photograph the entrance, the last site many would see before being ushered into a gas chamber. I was overwhelmed by the weight of sorrow and hopelessness many must have felt when they entered here. I knew my grandfather had felt the same at Dachau.

Our last stop of the day brought everything full circle. We visited the art exhibit Negatives of Memory: Labyrinths by Marian Kołodziej, a former prisoner at Auschwitz.

His haunting artwork covers the entire basement of St. Maximilian Kolbe Franciscan Church in Harmeze. For years the celebrated set designer never spoke of his time at Auschwitz, but a stroke in 1993 seemed to unlock those memories. He began to paint feverishly as if in a rush to illustrate the horrors of life within the camp while he still could. He didn’t stop until his death in 2009.

Reliving the nightmare

As I walked from room to room, it became clear that the torture endured by those who survived the Holocaust never ended. Like Kolodziej, they spent the rest of their lives reliving the nightmare. He shared his pain through art, my grandfather shared his through his photographs and stories from Dachau.

Throughout my life I had listened to the stories, watched documentaries and read books about the Holocaust, yet it was here, in this dimly lit basement, that the pain, fear and hopelessness they experienced fully revealed itself to me. Everyone who entered these camps, prisoners or the soldiers who liberated them, would bear the burden of trauma and guilt for those who didn’t make it out. So their memory lived on.

And here I was, a writer covering a conference while fulfilling my grandfather’s wish to share these stories so they would never be forgotten. It allowed me, in some small way, to honor the burden they had carried for so long.

Photos at top: (left) Photo of Laura Kelley’s grandfather, Curtis Smith, as a GI during WWII who helped liberate one of the camps during the Holocaust. (At right) The entrance to Block 10 at Auschwitz’s main camp, where countless prisoners – mainly women – were subjected to inhumane medical experiments that left enduring scars on history.

.png)

.jpg)