When Kimberly Mendoza arrived in Krakow, Poland for a conference on the role of Nazi doctors in the Holocaust, she was unprepared for how deeply it would affect her.

“When I toured these places and listened to the survivors recount their experiences, I felt a profound sense of chaos, fear and unimaginable suffering they endured,” said Mendoza, MD, a fourth-year anesthesiology resident at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “I’m still processing it on a personal level.”

Medical Review Auschwitz: Medicine Behind The Barbed Wire, brought together young medical professionals from across the globe to visit some of the most infamous concentration camps of World War II and discuss the harrowing crimes committed by the medical community during that dark chapter of history.

|

Full series: Medicine Behind the Barbed Wire |

Mendoza’s connection to genocide is not abstract. Her family history is marked by trauma from the 36-year Guatemalan Civil War that reached its height in the 1980s and included mass killings, rape, torture and genocide. Some 200,000 people were killed.

Many of the victims were the indigenous Maya population who the government viewed as aiding and abetting Marxist rebels.

Deeply personal atrocities

“It’s something I carry with me every day. Members of my family were lost,” Mendoza said.

For Mendoza, this shared history of violence and displacement makes her desire to understand the atrocities of the Holocaust both academic and personal.

“I wanted to study the Holocaust not just from a textbook perspective but from a deeper, human standpoint,” she said. “I wanted to understand the intersection of trauma, medicine and family so that it can help inform how I care for my patients and how I process my own generational trauma.”

She was particularly moved by firsthand accounts of survivors such as Ivan Lefkovits whose work focused on the neurological impacts of starvation.

“This case report is about me,” Lefkovits said in his presentation.

Impacts of starvation

He described in haunting detail how his own body and mind suffered during the brutal starvation experiments conducted in the Nazi concentration camps.

“We learn about these treatments in medical school, but we rarely hear about their origins. It's essential that we confront the fact that much of what we now consider standard practice came at the expense of human lies. Acknowledging this history is a way to honor the lives and ensure we never forget how those advancements were obtained.”

– Kimberly Mendoza, MD, a fourth-year anesthesiology resident at CU Anschutz

“His words painted a raw, visceral picture of what prisoners went through. It wasn’t just statistics and history – it was deeply personal and affected me on an emotional level,” Mendoza said.

Lefkovits said the research on starvation is still used today in treatments for eating disorders and other conditions. The ethical cost of that weighs heavily on her.

That same dilemma faces other medical professionals. Is it ethical to use medical treatments developed by torturing others?

‘Honor the lives’

“We learn about these treatments in medical school, but we rarely hear about their origins. It’s essential that we confront the fact that much of what we now consider standard practice came at the expense of human lives,” Mendoza said. “Acknowledging this history is a way to honor the lives and ensure we never forget how those advancements were obtained.”

Mendoza is determined to carry the lessons she learned in Poland into her own practice.

“As a chief resident, I see it as my responsibility to make sure those coming into the medical field understand the importance of these conversations,” she said. “We must create space for dialogue about ethics, history and humanity so that we do not repeat the mistakes of the past.”

On a personal level, Mendoza is committed to confronting her own trauma to ensure the memory of the Guatemalan Genocide and all other genocides are not forgotten.

“We think of the Holocaust as this isolated, singular event that we must never repeat but the truth is the genocides have continued around the world and many are forgotten or ignored,” she said. “Being silent allows the cycle of violence to continue. But if we speak out, if we listen, if we acknowledge the pain, we pass that knowledge onto future generations to try and keep these horrific events from ever happening again.”

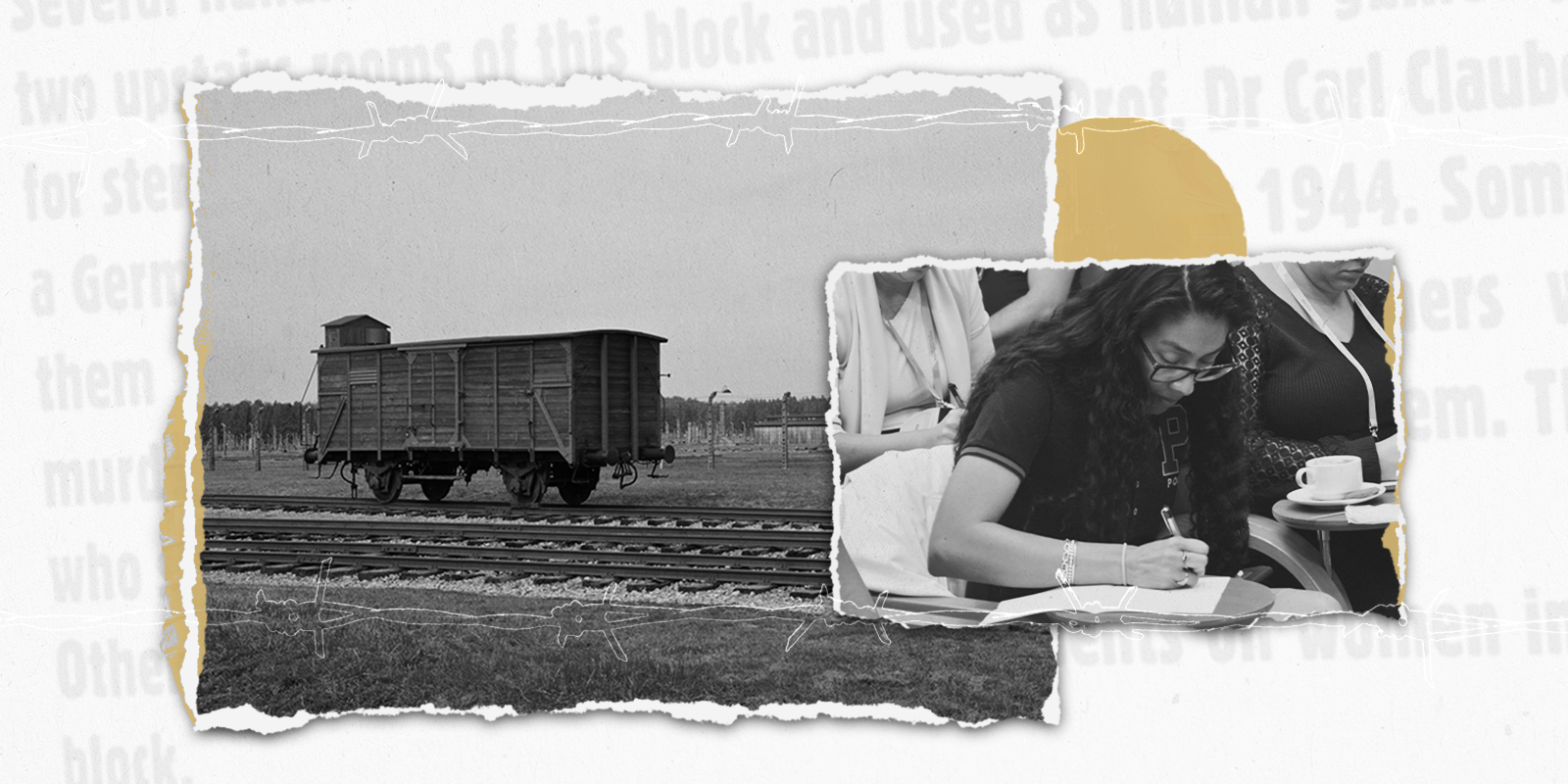

Photos at top: (left) This train car, once used to transport countless victims to Auschwitz-Birkenau, now sits at the unloading dock where hundreds of thousands were sent straight to the gas chambers. A chilling reminder of the horrors that unfolded here. (At right) Kimberly Mendoza, MD, participates in a workshop in Krakow, Poland to apply what she has learned at the conference to lessons for future medical professionals.

Israeli pediatrician reflects on her grandfather, who was the youngest twin to undergo Nazi medical experiments perpetrated by Mengele

At age 4, Josef Peter Pettychek Kleinmann Grünfeld became the youngest twin to undergo the Nazi medical experiments perpetrated by the infamous Josef Mengele at Auschwitz.

The boy routinely endured cruel and unnecessary procedures by German doctors who viewed him and other Jews as “sub-human.” His older sister was gassed, his mother taken away and presumed executed and his twin sister Marta simply vanished.

“His search for Marta was a lifelong journey. Even after all these years our family continues it hoping that one day we can finally have closure,” said his granddaughter Moran Ezrai, MD, a pediatrician from Israel.

Ezrai was taking part in the sixth annual Medical Review Auschwitz: Medicine Behind The Barbed Wire conference in Krakow, Poland. The conference is a gathering of young medical professionals from around the globe who discuss the crimes perpetuated by the medical community during the Holocaust.

This year’s meeting was held in September and included fellows from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and medical professionals from hospitals throughout Israel.

For participants like Ezrai, the Holocaust is deeply personal.

Her story is not just one of history, but of a trauma that endures. Against all odds, her grandfather survived Auschwitz but it wasn’t until she visited the camps that she fully grasped what he had endured.

Grünfeld was saved due to the Nazi infatuation with twins. Mengele subjected twins to all manner of torture from freezing them to death to trying to replicate genetic traits they carried.

“Even though he was young, he remembered the forehead injections, skin biopsies and painful drops placed into his eyes,” Ezrai said. “These procedures left him with lifelong health issues he battled until he passed away in 2017.”

After the war, he was adopted by several families but his search for his twin sister never ended.

Ezrai’s bond with her grandfather was particularly meaningful because of her own close relationship with her twin brother.

“It’s very personal to me because my brother and I are very close. My grandfather always reminded us to be thankful for each other because it was a bond he wished he had with Marta,” she said.

Grünfeld lived long enough to see Ezrai become a medical student, a dream he embraced despite his deep-seated fear of the medical profession, a lingering effect of his Auschwitz trauma.

He had a routine speech, which he gave to teenagers he accompanied in tours to Holocaust sites in Poland and asked them to pledge to: “be good children to your parents, be good siblings, be good citizens” and to her he added, “be good physician to your patients.”

She carries these words with her in her daily practice amid the challenges she often faces in Israel including treating victims of the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attack that killed over 1,200 Israelis.

When she’s exhausted from long shifts at the hospital, his voice reminds her to treat every patient the way she would her own child, to be compassionate no matter how tired she is.

“He'd remind me not to lose hope, that I was like one of the rare flowers blossoming from the ashes,” she said. “So when I had my first daughter, I whispered to her that she was one of the butterflies who would nourish those flowers, helping us rebuild this beautiful garden – even in the face of all our struggles.”