What is an ACL tear and how is the injury treated?

The ACL is one of the main stabilizing ligaments in the knee, and a tear is when that ligament ruptures. Think about a rubber band or a twig snapping. It typically happens during a non-contact pivoting mechanism – someone plants and twists, and then feels a pop. It can happen during contact, such as while playing soccer where someone’s getting into a collision, or football when someone takes a blow to the knee. Less commonly, it can happen during lower-energy mechanisms such as stepping off a curb.

There are rare cases in ACL tears where they can heal, but the vast majority don’t, and the knee remains unstable. Most often, but not always, patients require surgery.

It’s been reported that women athletes tear an ACL at a rate of roughly two to eight times more often than men, and that one in 19 female soccer players will tear an ACL. Why are women athletes more susceptible to this injury?

It’s multifactorial, meaning there are a lot of different components, and we don’t fully understand it. The things we do understand are, first, women’s anatomy is different in that females tend to have a wider pelvis and that creates a sharper angle to the knee, which then places the knee more at risk for this injury.

Secondly, in the middle of the knee there is a notch and it kind of looks like an archway. Women in general tend to have a narrower archway, which creates more impingement on the ACL, which lives right in that archway. So that can create compression on the ACL and can lead to injury.

Then there are hormonal risk factors. We’ve learned a lot in the last decade or two that the menstrual cycle really impacts the rate of knee injury and different sex hormones, such as estrogen and progesterone, play a role. So that’s another risk factor that we don’t fully understand yet. There are also neuromuscular differences where women tend to be quad dominant in their training regimens. That puts other muscle groups in a relative weak spot. And so, the dynamic control of women’s knees tends to be more deficient than men’s knees.

Then there are a lot of things we just don’t fully understand. Could it be field surface – turf vs. grass – and do women tend to play on poorer surfaces more frequently than males? So far, there are no clear answers to those questions. Cleats were designed for men and then modified to fit the woman’s foot, but not necessarily to accommodate female anatomy. Could they make a difference? And then I think a lot of it just ends up being bad luck.

Why are ACL injuries so hard for an athlete to come back from – both time spent in recovery and the ability to get back to the same level of performance?

Yeah, it’s very interesting. The literature we quote to our patients is 85 to 90% or more of athletes will get back to sport. We’re talking high school, collegiate, professional athletes – and then the weekend warrior getting back to skiing, snowboarding, etc.

With high-level athletes, on average it’s about 60 to 70% who get back to same performance levels. It’s very, very humbling. There are a lot of reasons for this. There’s the physical: Sometimes even though the ACL might be perfect and stable, the muscular control just doesn’t come back. There is some data to suggest that it takes two years to fully recover from an ACL. But for a professional athlete, how do you keep them out for two years, especially if they’re passing physical tests and feeling ready to go?

There are also psychological reasons, and we’re learning more about this in terms of the fear of re-injury and the hesitation. So people tend to potentially go less hard. When we do research, we look at return-to-play rates as well as at what level. And both are important to be able to counsel your patients on expectations.

The current standard of care for an ACL is a reconstruction – either using the patient’s own tissues or cadaver tissue. But there’s a shift toward repair where you’re not using any of those implanted tissues. Is that correct and why the shift?

Yes, so the standard of care is to reconstruct the ACL with either a tendon graft from the patient’s own knee or from a donor. For the vast majority of our athletes, we’re typically doing it from their own knee. So donor tissue is typically reserved for older patients, lower-demand patients. But for the higher-level athlete, and anyone who is younger – under 30, 35 or maybe 40 – we’re trying to use their own tissue.

When the ACL tears, it’s not like it snaps cleanly in half. Think of a frayed rope and the fibers are all over. And so, to get those to heal, it’s almost impossible. Direct repair of that frayed tissue was the original technique over four decades ago when ACL surgery started. Back then, surgeons stitched it back together through an open approach, and often put patients in a cast. Patients did not do well with that. They got stiff knees and their re-tear rates were high.

And then reconstruction became a technique that was much more favored. You’re taking a piece of tissue from somewhere in the knee (that doesn’t need it) and you’re putting it where the ACL used to exist. It was pretty effective and got athletes back to play, so it became the standard of care, compared to direct repair. Over the last three decades, our reconstruction techniques have revolutionized. In fact, even in a few years, my technique has changed based on a better understanding of how to make better grafts from the patient’s tissue, better implants, and better techniques that are more minimally-invasive and cause less patient morbidity. This results in less donor-site morbidity, while still allowing a great graft for the patient.

There are tear patterns where, instead of the frayed-rope analogy, it just tears on one end, and that’s typically off the thigh bone. If you can recognize that tear pattern, if it’s repaired directly to the bone where it tore, the ACL has a chance of healing. In fact, we’ve seen patients get back and feel like they have a more normal knee (compared to reconstruction). So if it can heal, not only is it stable, but the patients tend to be more satisfied because they feel like their knee is now normal. Compare that to reconstruction patients who often feel like their knee is stable and they can get back to sport but they still feel like it’s their surgical knee. They don’t necessarily feel like it’s a normal knee.

So repair is very attractive if we can find the right tear pattern, with new technologies and implants, we can offer a repair. And the repair can help lead to a more natural knee without taking away any tissue from anywhere else, and still give a very stable result – as good as the reconstruction. It’s certainly not for everyone and not every tear pattern. In addition, there’s now the use of scaffolds to help encourage these tears to heal via direct repair.

I take it you are referring to scaffolds of biological tissue?

Correct – specifically scaffolds of collagen. Basically, collagen is in so many of our tissues – skin, tendons, ligaments, it’s in the ACL. A scaffold of collagen, combined with potentially some growth factors, combined with potentially a biologic substance such as platelet-rich plasma or bone-marrow augmentation, can be added to the ACL repair. The whole goal is healing. If we can encourage the ACL to heal, we’re going to be very happy. The same goes for reconstruction: If we can encourage the graft to heal inside the knee, patients are going to do really well.

Is there a way to help prevent susceptibility to torn ACLs through athletic training programs?

The number one way is with prevention programs. Essentially, these boil down to performing what we refer to as a dynamic warmup, before any training session, before any match. It typically involves, on average, about 15 to up to 30 minutes of different exercises that are designed to get the body warmed up in a way that probably we’re all not necessarily doing as weekend warriors. You’re mimicking movements that you’re doing during training, during the match. You’re getting your knees, hips and core all ready to go. And there are different programs. They are easy to implement and don’t require a lot of equipment – just time. So, that’s the crux: We know that there are prevention programs, but they’re not always implemented.

Do you think there will ever by a holy grail type of procedure where an athlete with a torn ACL can expect to heal, return relatively quickly and perform at their normal level of performance?

I think the holy grail over the next decade or so is going to be a marriage between personalized medicine, biologics and mechanics. I think if we can marry a biologic repair or reconstruction with a mechanically sound repair or reconstruction, we may have an opportunity to get the ACL healed quicker with excellent reliability, and therefore get athletes back quicker than the standard kind of nine months or more with good predictability.

The personalized medicine approach comes in where we can draw some blood from the patient and figure out, yes, you need this, but the next patient who has different genetics and different growth factors in their bloodstream, whatever that might be, they need something different. Then, if we can combine the biologics with the mechanics and tailor that to the specific patient, we may be able to get there. I think what athletes want is an ability to get back to their sport at the same level quickly. What surgeons want is the exact same thing. We’re just not there yet, but I think there are opportunities to get there.

Photo at top: Megan Rapinoe (center, left) and Alex Morgan celebrate together. Both women have sustained ACL injuries during their careers.

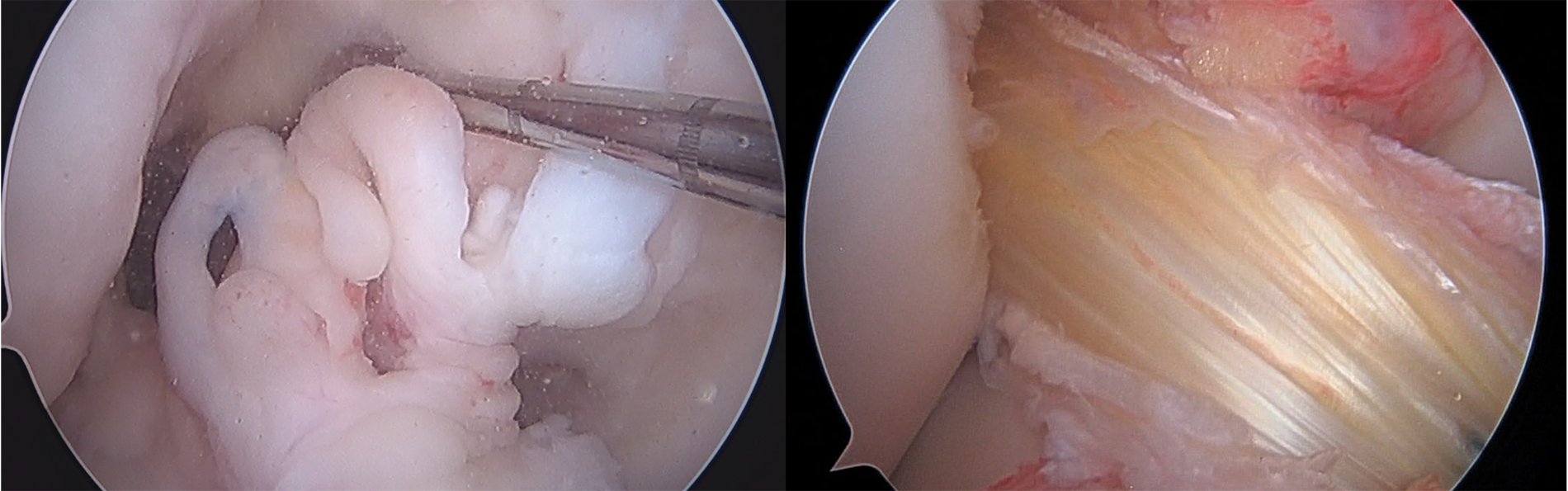

Arthroscopic photo of a patient's knee undergoing ACL repair. Source: Rachel Frank, MD.

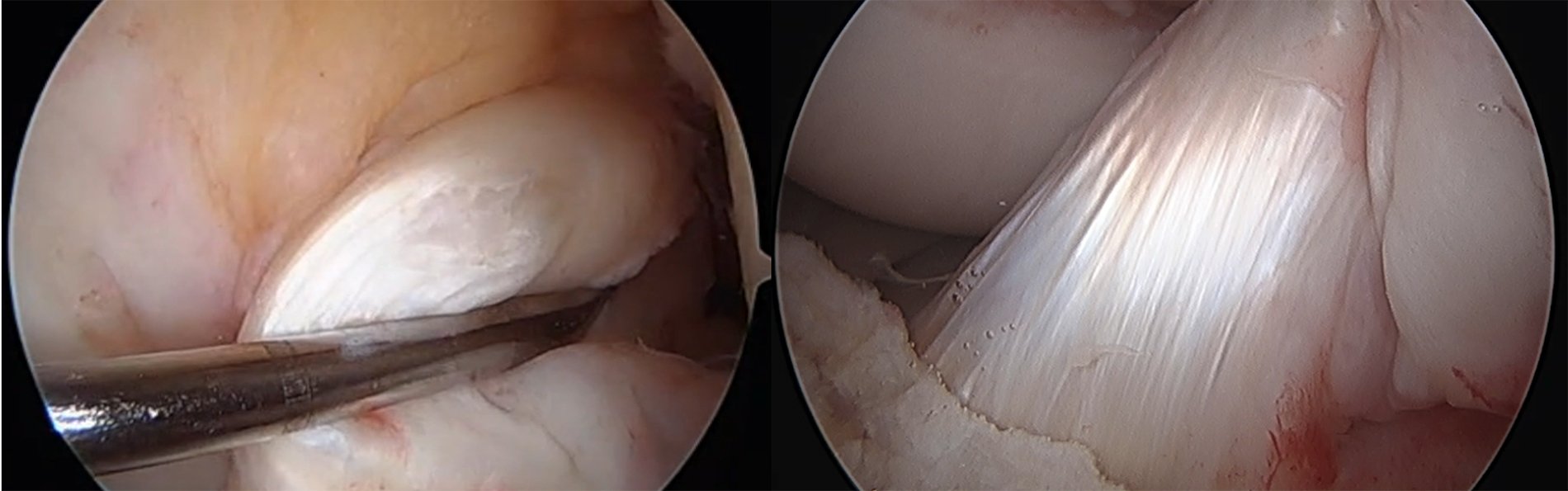

Arthroscopic photo of a patient's knee undergoing ACL repair. Source: Rachel Frank, MD.