What is human trafficking? Could you recognize it if you saw something suspicious? What are the signs that someone is being trafficked? What if it was one of your patients? What do you do?

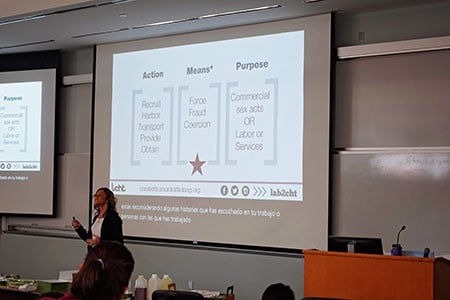

Kara Napolitano teaching CU Nursing students about human trafficking |

Those are the questions Kara Napolitano, a research and training manager with the Colorado-based Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking answered for nursing students at the University of Colorado College of Nursing at Anschutz Medical Campus. The CU Nursing Student Nurses Association hosted the training last month.

“There’s so much to know about this crime and so few people understand the complexities and nuances of it,” she says. “Human trafficking isn’t like what you see in Hollywood. It’s not Taken or The Sound of Freedom. Those movies always show little girls being kidnapped into sex slavery. That’s not the reality.”

What Is Human Trafficking?

Human trafficking is a severe form of exploitation for labor – including sex work – through the means of force, fraud, or coercion.

Napolitano says that 99% of the time, victims know their perpetrator, whether it’s a family member or someone of authority. Seventy percent of the time, it’s someone the victim knows and loves. Of that 70%, 30% of the time it's a family member, and 40% of the time an intimate partner. Other categories fit into that last 25-29% are other people in power, including employers, teachers, or religious authorities.

She says the perpetrators know the vulnerability of their victims. The victim could be looking for love because they’re not receiving it from their family. They could be looking for housing because they’re homeless and need a warm place to stay.

“These perpetrators are meeting the needs of the victims. They’re not kidnapping them, but the victim becomes dependent on this person,” she says.

Is This Happening in Colorado?

Napolitano says human trafficking is present in Colorado. She gave several examples, including one about a child whose parents were selling him for sex in a Denver suburb.

CU Nursing students learn about human trafficking. |

“We know where vulnerable people are in our communities. We might turn away from it, but it’s no secret where they are,” she says. “Traffickers go to those places and recruit victims.”

Human trafficking also relates to people working in Colorado’s agriculture and farming industries. She says labor trafficking disproportionately affects immigrants, impacting about 50 to 60% of labor trafficking cases in Colorado.

“Labor trafficking is three times more likely to happen in Colorado,” she says. “In Denver, it’s happening in hospitality and construction. But we also see it in any situation where there’s a subcontracted labor situation.”

She says traffickers will keep up to 20 people in a two-bedroom house on a farm, confiscate their passports, and transport them from the house to the farm, not allowing them to go anywhere else.

“Traffickers will say, ‘Do this or I’ll have your parents deported. I’ll have your whole family deported’,” she says.

What Nurses Need to Know

Napolitano says every healthcare provider she knows has seen signs of human trafficking. Nearly 88% of survivors had contact with a healthcare provider while they were trafficked, and close to two-thirds of them were treated in an emergency room setting.

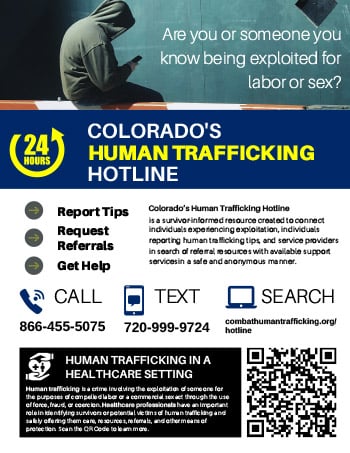

Reporting Human Trafficking |

Download the Hotline flyer |

“You see a patient and they’re injured. They might be malnourished. They might be engaging in risky behaviors, and all of these things lead them to need healthcare. So this is going to intersect with your work,” she says.

She says nurses should look for things like evidence of a prolonged injury because oftentimes traffickers won’t let the victim seek medical help. Patients who haven’t slept or eaten in days might show up in a state of psychosis and can’t explain what happened to them. Patients might show up multiple times for sexually transmitted infections (STI) screenings or abortions over a short amount of time.

“A patient might have someone speaking for them on their behalf, so that’s a big red flag to look for,” she says. “Is someone checking their phone often, or gets angry when you suggest they leave? Is their trafficker waiting in the parking lot? Find a way to separate the patient from the person who brought them in. It doesn’t mean the patient will disclose what’s happening to them, but it allows you to say, ‘I’m worried about you’.”

Creating Protocols

Napolitano encourages nurses to learn protocols at their hospital or clinic for human trafficking. If there are not any protocols, she encourages nurses to speak up and create them.

“Be a champion and be the person that stands up and says, ‘We have to get this training so we can all understand what’s happening’. Then, you can develop protocols,” she says. “This is about giving nursing students an overview of human trafficking so they can be advocates for additional training,” she says. “It’s about embedding this at the beginning of someone’s healthcare journey so they’re aware of what could be happening.”

Protocols could include screening questions to ask a patient, having a social worker meet with the patient, or offering a phone number for a follow-up visit.

“Having open conversations about what could happen or might happen is vital. If you leave (this presentation) and don’t talk about it for five years, then one day at 2 a.m. someone might show up at your hospital who’s been trafficked, and suddenly no one at your place of employment has been trained on what to do,” she says.

“This is something happening in our cities and towns,” Napolitano adds. “It’s happening in our ERs, so we need to be champions for this issue and make people, including our nurses, know that this is happening. We need to start thinking in terms of making our communities safer because everyone can have such a big impact in making that happen.”