Forty-eight hours after graduating from the University of Colorado School of Nursing in Denver with a bachelor of science degree in 1967, Mary Dempsey volunteered for the US Army. The new recruit was shipped to Chu Lai, Vietnam to nurse the wounded during the war's bloodiest year. Dempsey took care of wounded soldiers and Vietnamese for 12 hours a day, six days a week. She gave them medicine, started IVs, and comforted people who’d been burned by napalm, infected from booby-trapped stakes, and torn apart by bullets.

“I remember the sickest ones,” Dempsey, RN, MSN told a history student. “The guy who was paralyzed, the guy with the burn and the guy I went and sat with. We were waiting for his heart to stop beating because he’d taken a bullet between the eyes. You remember that and you can’t get rid of it. So, you just go with it.”

War

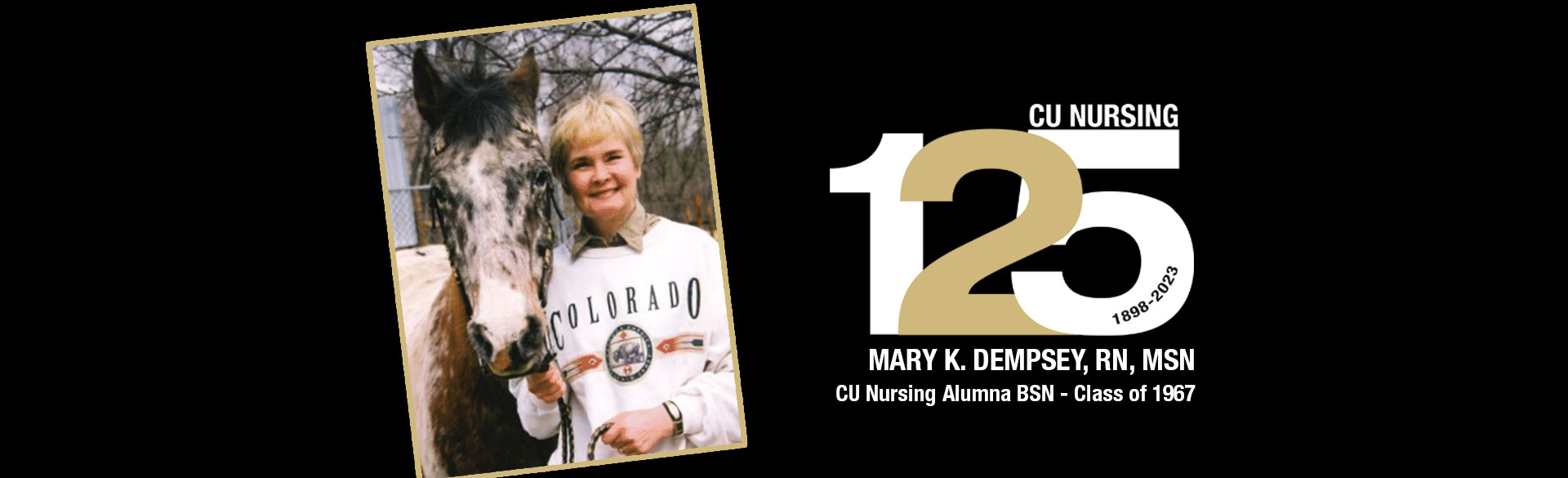

Mary Dempsey, RN, MSN in Vietnam |

During surprise attacks by Viet Cong during the Tet Offensive, US soldiers woke Dempsey in the middle of the night and evacuated her and others from the war zone. Months later, other intensive care nurses, including Sharon Ann Lane, were deployed to work at the same hospital in Chu Lai. Just two months into their tour, an enemy rocket tore through the Vietnamese hospital, killing Lane. The 26-year-old was the only American nurse killed in action during the war, according to the Army Historical Foundation. Today, she is one of 58,281 names engraved on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C.

The suffering and death Dempsey witnessed during her 2.5 years of service in the US Army and the knowledge of Lane dying haunted her mentally and physically for years. The political, economic, and social forces at the time also led her down a career path of providing specific care for people from different cultures, quality care for the destitute, and home-based care for the sick and elderly.

Today, the 80-year-old suffers memory loss and lives in Montana with her husband John Noreika, Sr. Recently, he wrote a memoir called The Life and Times of Mary Katherine Dempsey-Noreika. The book explores her time at CU Nursing where she earned bachelor's and master’s degrees under the tutelage of Dr. Lorretta Ford, the pioneer who co-developed the nation’s first nurse practitioner program at CU College of Nursing.

“CU Nursing and Dr. Ford had a profound impact on Mary K,” says Noreika, Sr. “They shaped her entire idea of what nursing was about. The coursework and leadership there shaped her life.”

The book also describes Dempsey’s impact on healthcare nationwide. But at its heart, the biography is truly a love story.

“I just feel privileged that she fell in love with me and thought I was worthwhile,” says her husband of 39 years. “She had such an extraordinary life, such a tremendous humanitarian from a nursing perspective and also nursing leader. She was constantly putting her life on the line for other people, and so I thought the least I could do was try to tell her story.”

Mary K. Dempsey marries John Noreika, Sr. in 1983 |

Love

Noreika, Sr., met Dempsey in the summer of 1983 when they both applied for the same job as executive director of a certified home health agency in up-state New York. Dempsey got the job. Noreika then took a position with the regulatory agency overseeing healthcare development at that time, including Dempsey’s agency. During a meeting one day, they discovered they both shared a passion for healthcare and Appaloosa horses. On their first date, they went horseback riding.

“It was a profound connection. We had been riding in the setting sun and both of us thought it was magic. It was profound that we each felt we had found the person we could be with for the rest of our lives. Not only in healthcare, but we shared a love of horses and the outdoors,” says Noreika, Sr. “We then began a very purposeful romance, knowing that if we screwed this up, we had lost the opportunity of a lifetime. And we didn't screw it up.”

Healthcare

Ten months later, they married. Together, they were an unstoppable force to improve healthcare. Over the years, they fought to improve healthcare for seniors by offering chronic care, preventive medicine, healthy aging, and long-term care. Their efforts took them to places nationwide.

Immediately after returning from Vietnam, Dempsey practiced as the head nurse at Fitzsimons General Hospital Intensive Care Unit in Colorado where she received a citation for Outstanding Service and “upholding the highest standards of professional competence and leadership.” She also taught at the CU School of Nursing in 1996-97.

In Arizona, she served a predominately low-income Hispanic community at a neighborhood health center. At the State University of New York School of Nursing in Binghamton, she taught and directed the family nurse practitioner program and helped improve and modernize that region’s healthcare system.

In Wisconsin, she transitioned the original visiting nurse service in Madison into a modern, integrated Medicare-certified home health agency. In Montana, she led the effort to fund and lead the first nurse practitioner training program at Montana State University’s College of Nursing in 1994.

Along the way, the Army nurse veteran had to fight for her own healthcare. Early after leaving Vietnam, she became sick with Sepsis or blood poisoning. She eventually recovered. Later, she battled chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from exposure to Agent Orange, a chemical herbicide used in the war. While her body healed, her mind still hid the horror of the warfare.

|

In all the years after leaving Vietnam, Dempsey rarely talked about it. She kept it distant, buried. Then, some fellow nurses invited Dempsey to see the Broadway musical Miss Saigon in New York City. She worried, but went. At the end of the play as Saigon fell and troops and medical workers were airlifted out of the country, Vietnamese actors screamed, “Don’t leave us! Don’t leave us!” And that was it.

“That opened the door for me,” Dempsey said. “I just cried and cried and cried…and I started talking about it.”

Noreika, Sr., remembers her falling apart in his arms after the play.

“She exploded in tears and sobbing that shook her whole body,” he said. “She experienced incredible guilt because she could not do enough to relieve the unspeakable suffering and save more lives. After she cried a long time, she went into a deep sleep… In the morning, she was radiant again.”

Today, while Dempsey’s memories fade, her devoted husband has captured her stories in the memoir along with her dreams for better healthcare for everyone.

“Mary K’s story can inspire the next generation of nursing students, faculty and donors,” says her husband. “In Montana, where we live now, that means helping Montana State University achieve the goal of eliminating the nursing shortage by 2030 and attracting and training nurse practitioners who will stay in the most rural areas, particularly the vast native nations to address the fact that Montana has one of the highest pregnancy-related death rates and highest suicide rates in the nation.”