By the time Karre Wakefield’s friends and classmates turned 16 and got behind the wheel, she had accepted riding as only a passenger. Wakefield was born with hydrocephalus, or excess fluid in her brain, which damaged her optic nerve and rendered her ineligible for a driver’s license in the state of Colorado.

Without correction, each of her eyes has 20/400 vision. Her right one is nearsighted, capable of focusing on details, but her left eye has trouble focusing, using it primarily for mobility and seeing “the big picture.” Learning to accommodate for her vision, Wakefield never held herself back, joining sports teams with her classmates as a manager and participating in everything she could.

“There was really nothing that any eye doctor at that point could do for me,” Wakefield says. “The technology hadn't come forward yet, so I just decided this is where I’m at, and I’m going to make the best of it.”

Finding her passion in music, Wakefield works in worship and speaks at women’s retreats today, living with her husband of over 30 years and her three children.

Discovering possibilities through rehabilitation

Although she never shortsighted her approach to life, she never expected her vision journey to shift gears. It wasn’t until a doctor visit for her general eye health about five years ago that a new lane emerged. Her eyes were considered healthy, but she was referred for further examination to Kara Hanson, OD, FAAO, director of the Low Vision Rehabilitation Service at the Sue Anschutz-Rodgers Eye Center and associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

“When I first saw her, driving really wasn't her goal,” Hanson says. “Back in 2017, her main goals were long term reading, short term reading, computer work, seeing distance detail, and music. She's pretty high functioning, but she wanted to learn more about what technology and devices were available to her.”

The Rocky Mountain Lions Eye Institute on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus is the one of the only eye centers in Colorado with a full-time, low vision rehabilitation specialist like Hanson, who spends an hour or more with each patient to understand their goals and needs. After a few visits, Hanson brought Wakefield back to feeling 16 again.

“She said, ‘With correction, I can possibly get you to a place where you could drive. Is that interesting to you?’” Wakefield says. “I just looked at her with a dumb look on my face, and I was like, ‘Huh?’ I've always wanted to drive!”

With training, driving tests, and the assistance of a low vision device, Hanson deemed Wakefield an appropriate candidate to drive on a restricted driver’s license. The device Hanson recommended for her was a bioptic, a miniature telescope mounted above the line of sight, on prescription glasses that correct her refractive error.

“We use it the same way that we would use our rearview mirrors,” Hanson says. “You glance into the mirror, see what you need to see, and then you're back looking through the windshield. When walking or driving with the bioptic, most of the time, you’re viewing through the carrier lens, which would have a regular distance prescription. Then, when you need to see detail, whether it's street sign, traffic signal, or the flow of traffic further ahead, you drop your chin down, get into the telescope, see what they need to see, and then get out.”

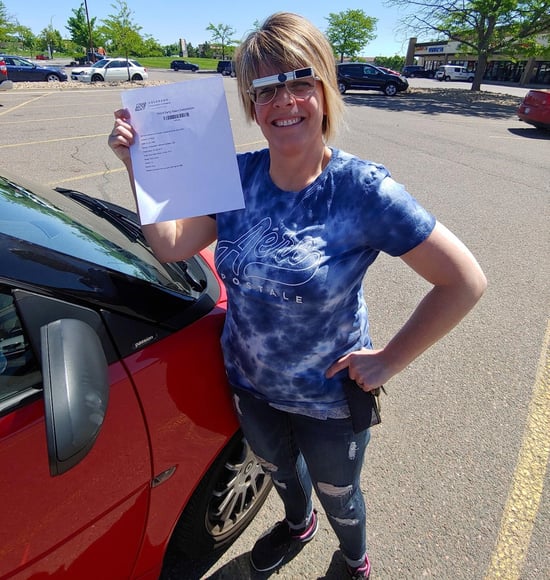

Karre Wakefield passes her driver's exam, wearing her bioptics.

While specialists like Hanson ensure patients are fitted with the appropriate magnification level to meet DMV requirements, she relies on the clinic’s occupational therapists to prepare patients for the driving portion. Once ready, patients are referred to certified driver rehab specialists for hands-on, behind the wheel training. It’s then up to each patient to pass their respective driving tests. Colorado is one of more than 40 states that allow for bioptic driving if patients meet certain requirements.

“Driving is not a goal that everybody is going to be able to attain,” Hanson explains. “The person has to have a certain amount of vision on their own without any kind of low vision device to be able to drive safely, and they have to be able to process the information fast enough to react to what they're seeing.”

Facing her fears

Although driving had always been a dream, Wakefield took the new opportunity very seriously.

“Driving is the biggest, coolest thing of this whole adventure for me because my freedom was literally getting opened up here after 30 years of watching everyone else get their licenses at 16. It was scary and cool at the same time,” she recalls.

“Technology is awesome, but it comes with great responsibility,” she continues. “Driving was one thing, but after going to rehabilitation, there was more testing that had to be done to see where my reaction time was, how I accommodated, and how I would do driving with a bioptic. It's slower than what an average person would be because I’m not only looking through the bioptic for a second, but I’m also 50 and getting older. It takes a little bit longer for our impulse to respond.”

Wakefield officially received her restricted driver’s license in 2019 and can test for a renewal in 2027. The restricted license limits her to daytime driving, safe weather conditions, and speeds no higher than 45 mph, but she goes the extra mile when it comes to precautions.

“I have to leave bigger gaps for people, so to help with that, I chose a smart car to be my vehicle of choice,” she explains. “The fact that it's small and I can see all four of my corners helps me not worry as much. Plus, in a smart car, nobody expects you to go fast. I even have the signs that say, ‘Please be patient student driver,’ and people think I'm learning at all times, and they accommodate that most of the time.”

Although additional training could allow her the chance to expand her driving capabilities, such as driving faster and going on highways, she’s happy to just be driving.

“I just want to go 45, get around to Target, King Soopers, and church,” Wakefield says. “I got about a 5- to 10-mile radius around my house where I'm able to do the things I need to, and it works for me.”

Asking for help is okay

Though she jokes that she will warn friends when she’s about to hit the road, Wakefield said this experience has made her so thankful for the outpouring support she’s received from family, friends, colleagues, and her vision specialists during this new venture. It’s also opened her eyes to a valuable lesson, especially for the low vision community.

“There is this healthy balance between two sides of a coin,” she explains. “You have to know your limits and boundaries of what you can and can't do, but you also need to try. Then, once you run into those walls during those challenges, it's okay to ask for help.”

Karre Wakefield smiles with her husband.

Karre Wakefield smiles with her husband.

She hopes others who live with low vision will use this advice to face their fears and live their fullest lives as soon and as much as possible.

“If there's any regret I have, it’s that I didn't ask for help sooner,” she says. “This technology didn't come into being, two years ago, or even five years ago even. Fear of the unknown can really block people with low vision because you get comfortable in your settings and it's scary to try new things, but when you have quality people around you that you trust to help you, then you work past the fear, which is just false evidence appearing real.”

“The technology's there, and the people are there,” she continues. “We have to believe that people around us are trying to make things better, not worse in our world. Lean into those things because otherwise I would never have driven.”

.png)

.png)

.png)