The eye cancer known as uveal melanoma can be deadly when it spreads to organs like the liver, but historically there was no reliable way to know which uveal melanomas would become metastatic and which would remain local to the eye.

“In uveal melanoma, about a third of patients die of their disease, and you can't tell by looking at it,” says Scott Oliver, MD, associate professor in the University of Colorado Department of Ophthalmology. “Being able to make that prediction with high accuracy has been an unmet need.”

Finding a biomarker

Working as a member of the Collaborative Ocular Oncology Group (COOG), the largest collaborative working group in North America of ocular and medical oncologists specialized in the treatment of patients with intraocular cancers, Oliver was one of several researchers who conducted a study to determine if the genetic profile of a uveal melanoma tumor can predict whether the cancer will metastasize. The results of the research were published in October 2024 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“We obtain a tissue biopsy on the tumor, which is done at the time of surgery, and send it off for analysis not just of presence or absence of genes, but the expression through the mRNA of those genes,” explains Oliver, also a member of the CU Cancer Center. “That gets condensed through a machine-learning algorithm into a simplified risk score that's basically class one versus class two. Class one is a good answer; class two is a bad answer.”

The study looked at the expression of 15 specific genes as well as the RNA expression of preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME), a separate biomarker associated with increased metastatic risk.

Treatment opportunities

Until recently, Oliver says, patients whose uveal melanoma spread to the liver had around nine months to live, and there were no effective treatments. Within the past couple of years, however, the Food and Drug Administration has approved the medication tebentafusp (KIMMTRAK) for metastatic uveal melanoma, making it much more important to identify the patients whose cancer is more likely to spread.

“By identifying the patients who carry the highest risk for metastasis, we're able to improve their surveillance, so we watch them much more closely,” he says. “We now know that early detection of metastasis gives us more options for being able to treat it and try to prolong survival, and that wasn't always the case.”

The biomarker testing has advantages for patients at low risk for metastasis as well, Oliver says.

“Our goal for the high-risk people is to find the metastasis before they have heavy disease burden,” he says. “For the people who are low risk, we're able to minimize their intervention and save health care expense by doing less surveillance.”

Future opportunities

Targeted therapies have not met the same success for uveal melanoma as they have for breast or colon cancer, but once they do, Oliver says, the 15-gene assay may serve another purpose — predicting which patients are likely to respond better to the treatment. The tissue registry that Oliver's co-researchers used for the metastasis prediction study has already yielded another soon-to-be-published study on driver mutations in uveal melanoma, and he predicts the data bank will help researchers better understand other aspects of the disease going forward.

For now, though, the research is proving to be a boon for clinicians who can use the new diagnostic tool to give patients more precise information about their diagnosis.

“It means we can answer the question for patients about how worrisome or how risky their tumor is,” he says. “For a long time, people have thought that all melanoma is bad, and we now know that some melanomas are less bad than other types. There are some people who need to be very concerned and watched very closely, then there are a large number of patients where we can tell them we've treated them locally, and their overall metastatic risk is very low. That helps to alleviate some of the anxiety they have about this disease's impact on their life.”

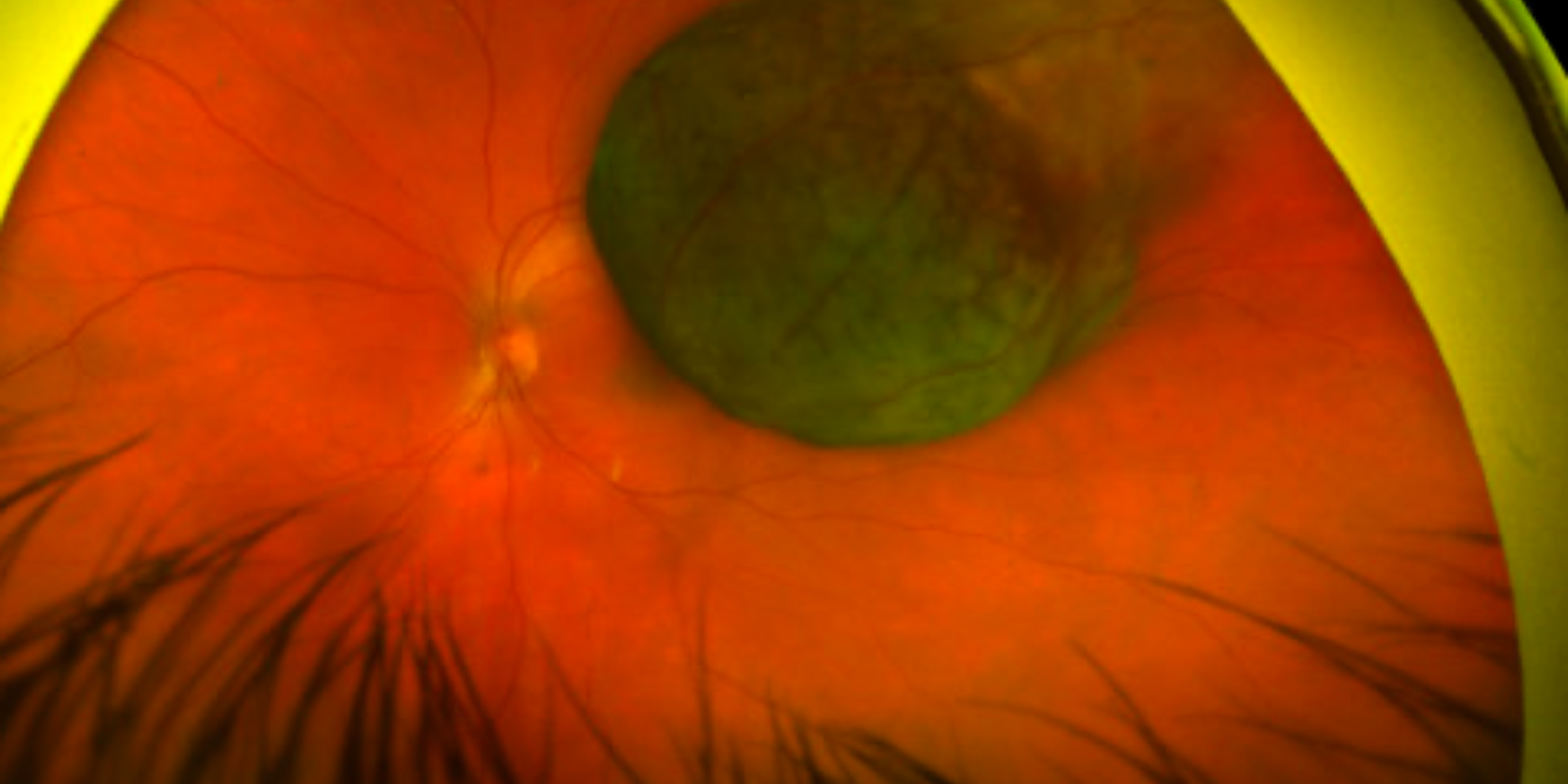

Featured image: Melanotic collar-button uveal melanoma.

.png)