Not many health care providers encourage their patients to break out their smartphones during office visits, but David Simpson, OD, an optometrist at the Low Vision Rehabilitation Service at the Sue Anschutz-Rodgers Eye Center on the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, prefers that they do. He treats patients dealing with a variety of vision-related diagnoses – the most common being age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy.

Technology can be a powerful tool for mediating vision loss, and Simpson wants people to avail themselves of apps and accessibility features in their devices.

“There’s a lot of fear that comes with such a diagnosis,” says Simpson, who is also an assistant professor of ophthalmology in the CU School of Medicine. “Many age-related eye conditions, unfortunately, get worse over time. One of my goals is to help patients deal with the changes they’re experiencing. My hope is it will alleviate the fear.”

A bold new world

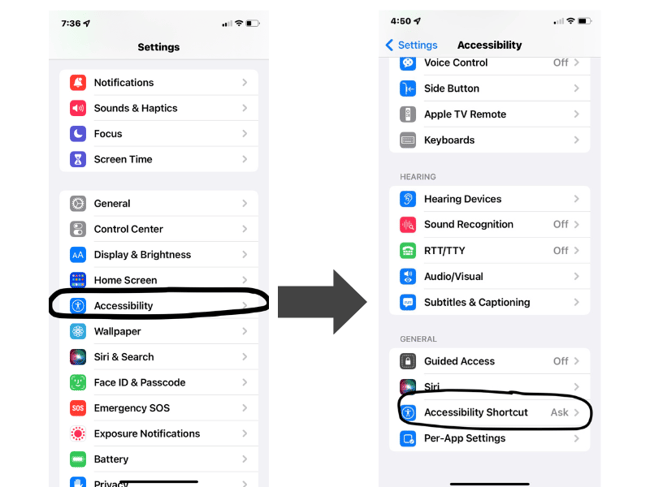

Accessibility settings are so important that Simpson urges patients to create a shortcut on their devices. On the device, open “Settings,” and scroll down to “Accessibility.” On older Apple devices, users may need to select “General” before “Accessibility.”

From there, the user can increase font size, adjust contrast, and set boldface text. The selection will apply to many of the apps that come with the device, such as contacts, calendar, settings, and text messages. When “Accessibility Settings” are opened, the user can scroll to the bottom and select “Accessibility Shortcuts” to quickly access features that can be turned on and off as needed, which is why Simpson recommends creating the shortcut.

“Sometimes I’m simply making patients aware of the tools that are available to them," Simpson says. "The real credit goes to those who develop the technology. Just being there when patients realize what they’re capable of doing is very gratifying.”

A few key tools include a zoom feature – a built-in screen magnifier to help read emails or texts, and a magnifier, which uses the phone’s camera to magnify objects. Users can also adjust their display accommodations, inverting text through the “smart invert” feature to aid reading and adapting the screen to low light conditions through the “filter” function.

Simpson advises that the built-in accessibility features for devices are more reliable than downloadable apps; something that was available a year ago might not continue be available.

There’s an app for that

After patients have familiarized themselves with their accessibility settings, Simpson suggests looking into apps that serve a variety of purposes, from magnifying images to identifying objects. Some even connect the user to a human volunteer. Many of the apps Simpson recommends below are less than $10, if not free, and are available on either iOS or Android devices.

SuperVision+ turns phones into an electronic magnifier. Although many apps have this functionality, this one, developed at Harvard University, features image stabilization. For Android users without a magnifier app built in, Simpson has recently been recommending downloading WeZoom or Visor, which have similar features to the iPhone Magnifier app.

Amedia NaviRec, Loadstone GPS, Goodmaps Explore, and Soundscapes offer assistance for walking navigation using GPS.

Color Inspector helps determine the color of clothing and other objects, while Examine Clothes Color describes the pattern on clothing.

To elevate visual assistance a step further, the following apps have text recognition built in and use the phone's camera and artificial intelligence to identify objects from currency and cans in the cupboard to signs and QR codes – Microsoft’s Seeing AI, Google Lookout, and Sullivan+. Users can point their phone camera at the desired object, and it will describe the object aloud, such as "Campbell's Tomato Soup" or "five-dollar bill." Apps offering object recognition include Dentifi-Object Recognition, Third Eye: Empowering the Blind, VocalEyes AI, and Aipoly Vision.

To receive assistance from a human volunteer, Simpson suggests Be My Eyes or Aira. The user can point their phone camera at any item, such as a restaurant menu, a sign, or food, and ask the volunteer a question, such as "how much is this check made out for?" The volunteer will then help them make sense of it.

The importance of tech evolution

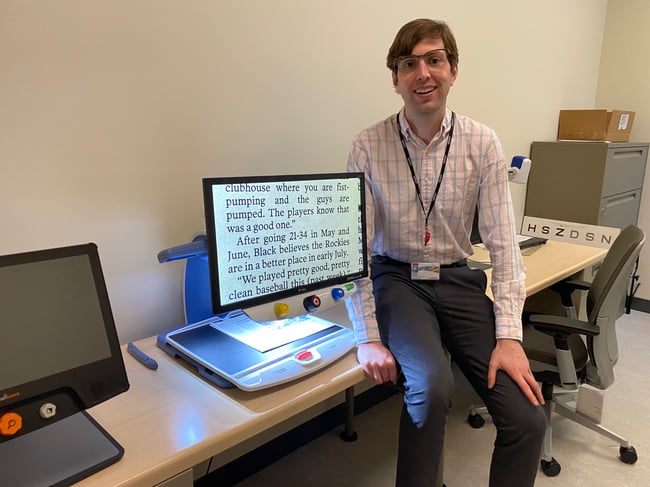

Before the widespread adoption of smartphones, patients with vision loss might have had to purchase high-dollar equipment, such as video magnifiers. Smartphones have empowered people in many ways not previously envisioned.

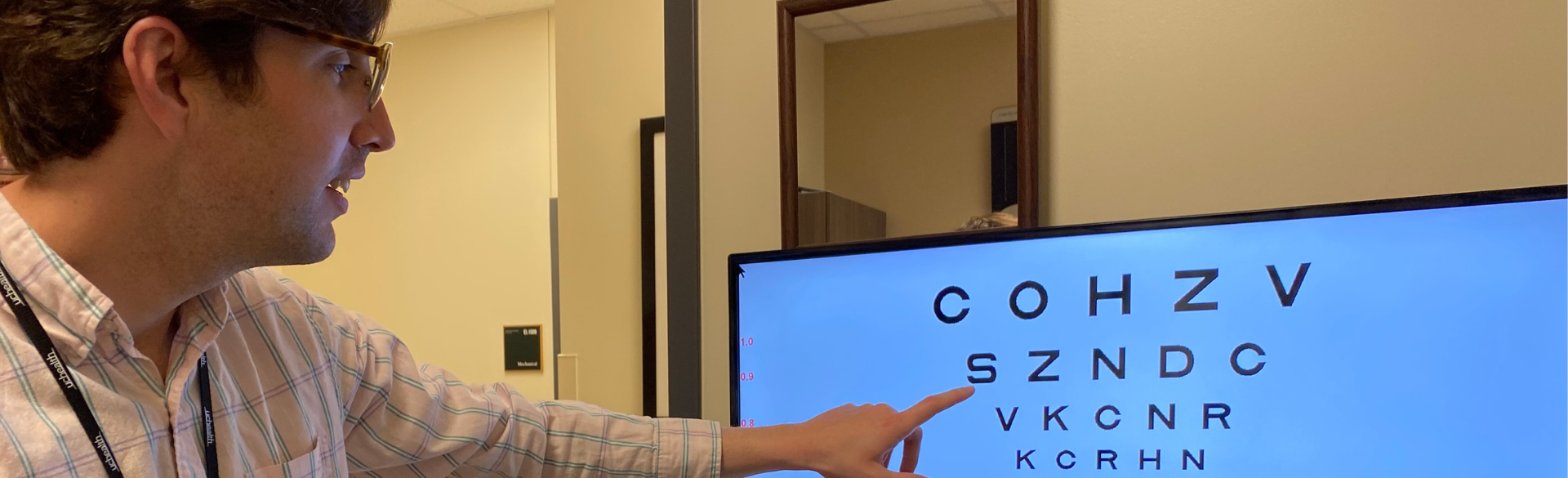

David Simpson, OD, demonstrates the use of a video magnifier, an assistive technology for low-vision individuals.

David Simpson, OD, demonstrates the use of a video magnifier, an assistive technology for low-vision individuals.

“It’s exciting when I’m able to demonstrate newer technology to patients who have had impaired vision for long periods of time because a lot of our traditional low-vision devices haven’t changed much over the past few decades," Simpson says. "I remember seeing a patient in his 60s with a history of uveitis who had fairly stable vision over most of his adulthood. I recommended Google Lookout, and when he came back in for his next appointment, he had been using it regularly."

"Breaking down barriers is important for people with any type of disability, including vision loss," Simpson continues. "Being able to address the visual goals of a patient without the need for new equipment, and often at a low cost, is only going to improve outcomes for our patients. Smartphones help us to do that, and I expect the technology will only continue to improve.”

.png)