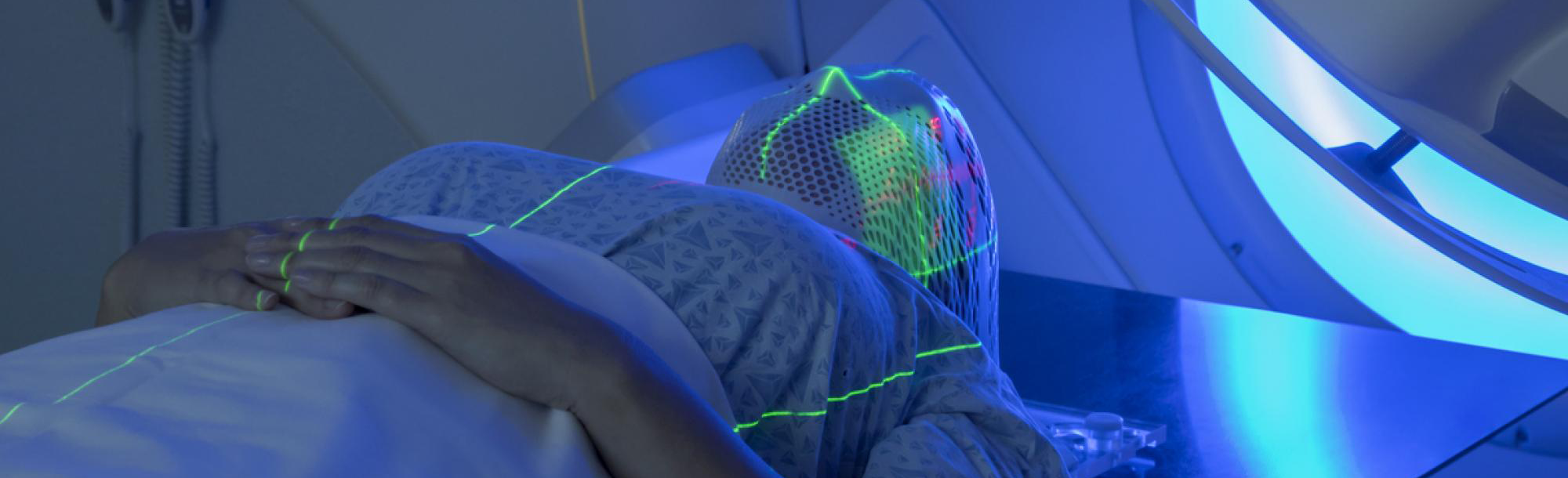

Whole-brain radiation therapy used to treat brain metastases is a significant cancer treatment that, while generally well-tolerated, can have serious long-term side effects, including dementia. Neither clinicians nor patients undertake it lightly.

Certain types of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) are known to preferentially spread to the brain. Thanks to the development of specific targeted therapies, many patients affected by some of these cancers are now also living much longer, so they have more time to develop later side effects from whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT). As a result, clinicians and researchers are looking for ways to move away from WBRT for these patients.

One better-tolerated alternative to WBRT is a technique called stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS). This involves focusing the radiation down to individual spots in the brain, sparing significantly more of the brain from irradiation. However, WBRT is still used for patients with very large numbers of brain metastases when the more intensive approach of SRS is not considered feasible.

Recently published research from the University of Colorado Cancer Center shows a new approach to limiting the use of WBRT in patients with certain types of NSCLC. It involves newer, oral targeted therapies that have been developed to penetrate and be active against cancer in the brain.

Using such therapies in patients with very large numbers of initial brain metastases, who typically would require WBRT if treated with upfront radiation, led to a significant reduction in the number of metastases – from a median of 49 to a median of five. This, in turn, allowed the majority of patients in the study to avoid WBRT. With fewer brain metastases, the potential for SRS as an immediate or later option dramatically increased.

All of the targeted therapies the patients took were tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). These therapies block different enzymes that cancer cells use to control growth and division. Specific genetic changes in the patients’ NSCLCs were used to determine which TKI to use in each case. Newer generations of TKIs have become increasingly effective at entering the brain, but little had previously been reported about their effect on the number of brain metastases and how that related to radiation treatment decision making.

”Down-staging is the technical term used to describe when a therapeutic approach can be de-escalated due to something beneficial that has been done to the patient,” says D. Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, Joyce Zeff Chair in Lung Cancer and one of the investigators behind the CU study. “Nobody wants more of themselves cut out than is needed to control their cancer. So, sometimes chemotherapy might be done before an operation to make the required resection more modest.

“Equally, what has happened here is an out-of-the-box approach extending that logic both to brain radiation and to targeted therapy for lung cancer. These data should help to convince radiation oncologists to sometimes hit pause and think about this multidisciplinary approach before suggesting WBRT. It should really help to change the outcomes for lung cancer patients for the better.”

Significant response on TKIs

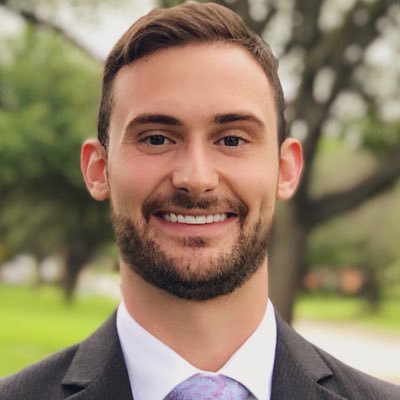

The investigators' retrospective research came about because of the increasing effectiveness of TKIs in reducing the size and number of brain metastases, explains researcher Jacob Langston, MD, a fourth-year resident in the University of Colorado Department of Radiation Oncology.

“Over the last five to 10 years, TKIs have really advanced so that now they do a really good job at being able to get into the brain,” Langston says. “TKIs have been an accepted treatment for a limited number of brain metastases, but we showed that patients who had a really high burden of central nervous system disease, meaning a high volume of brain metastases, saw a dramatic decrease in the number and size of brain metastases on TKIs. This led to CNS down-staging, where patients who might otherwise have had to receive whole-brain radiation therapy were able to receive more targeted treatment instead.”

Langston and his co-researchers reviewed records of patients treated by University of Colorado clinicians who had NSCLC and had either an ALK gene rearrangement, EGFR mutation, or ROS1 rearrangement. They also had extensive brain metastases – of the 12 patients who met the study criteria, the median number of brain metastases was 49 prior to beginning a TKI – and were followed closely with brain MRI surveillance about every two months.

After they began taking a TKI, 11 of the 12 patients achieved an objective CNS response. At the nadir, or the best response point when the number and size of brain metastases were lowest, the average number of brain metastases was five. The average time to reach nadir was about five months.

When later progression occurred, or to consolidate the already impressive TKI response, seven patients later received only SRS after they began taking a TKI. None received WBRT.

Reframing down-staging

“The concept of down-staging is something that previously had mostly been looked at in terms of neoadjuvant treatment, or treatment before surgery,” Langston explains. “For example, in breast cancer a lot of research has looked at treatments reducing the burden of disease so a patient doesn’t need as significant a surgery – instead of having a mastectomy maybe they could be down-staged to a lumpectomy.

“Radiation is different than surgery, but we’re starting to think of it in a similar way – what therapies can patients receive so they can be down-staged from whole-brain radiation therapy to more targeted radiation?”