“Tolerable.” “Manageable.” “Acceptable.” Those are terms that crop up often when researchers report on early-phase clinical trials of new treatments for lung cancer at medical conferences. But do terms like these accurately describe the side effects caused by experimental treatments?

And likewise, do presentations about early trials of new drugs sometimes “oversell” their effectiveness?

Those are key questions addressed by University of Colorado Cancer Center member D. Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, professor in the CU Division of Medical Oncology, in an analysis that Camidge says “shines light on how we dress objective efficacy and toxicity data in potentially misleading subjective terms.”

The analysis – “The Use of Investigator-Assigned Subjective or Judgmental Efficacy and Toxicity Reporting in Early Phase Clinical Trials of Lung Cancer Treatments” – was published recently in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology.

The first glimpse

Camidge notes that early-phase clinical trial data presented at conferences are often the medical community’s first glimpse of a new treatment’s efficacy and toxicity, especially when a peer-reviewed publication of trial results is still pending.

“Although such agents may traditionally not be licensed for routine practice at the time, these data may well influence a patient’s or treating physician’s enthusiasm for enrollment in a clinical trial of the same agent,” the new paper says.

Camidge cites his long experience of attending cancer meetings where early trials of new treatments are described.

“Maybe we’re all optimists at heart, but the habit tends to be to oversell the efficacy and undersell the side effects,” he says. “Honestly, I’ve sat in so many meetings where I could predict the conclusion about whatever new drug was being developed – ‘This is a well-tolerated treatment, with encouraging early signs of efficacy’ – and I’d wonder, ‘Did you write that before you even got the results?’”

He adds: “The range of effectiveness where people will say ‘this is encouraging’ is all over the place. And there’s a massive range of side effects that are described as ‘acceptable.’”

→ Ross Camidge Honored By the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer

ISJET at ASCO

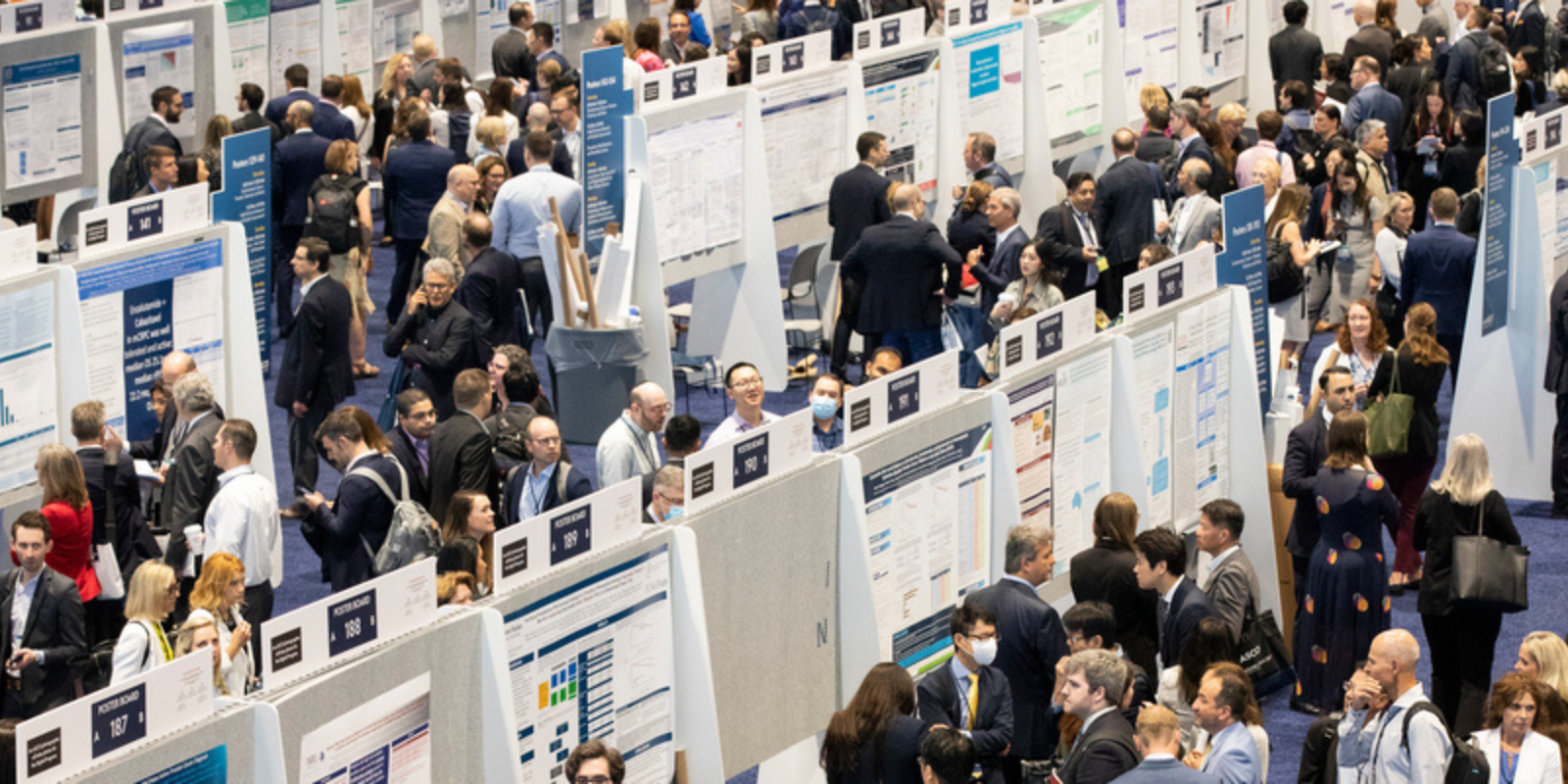

The new paper describes a review of 100 abstracts on Phase I and II clinical trials involving lung cancer that were presented at the 2024 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the world’s largest cancer conference.

It reports that what the paper calls Investigator-assigned Subjective or Judgmental Efficacy and Toxicity terms, or ISJETs, were used in 88% of the studies to describe toxicity side effects of new treatments and in 41% of the studies to describe efficacy.

Camidge’s paper argues that use of ISJETs can reflect a researcher’s subjective interpretation and judgment, rather than using standardized, objective criteria, potentially leading to biased or misleading data analysis. It also argues that the use of subjective terms to describe treatment effects can vary greatly between different investigators, depending on their individual perceptions and opinions, and lack standardization.

Adverse events

Camidge also reported that in describing “adverse events” caused by new treatments, only 12% of the 100 studies distinguished between grade 1 (“mild”) adverse events and grade 2 (“moderate”) events.

He says there may have been less importance to making that distinction when testing short-term treatments like chemotherapy, which present what he calls “a short shock to the system,” but it’s more important in describing the effects of long-term, “chronic” treatments.

“If you’re on a pill for years, even low-level side effects become burdensome,” Camidge says. “So, saying the effects are only grade 1 or grade 2, and therefore calling that acceptable, is just unacceptable. Grade 1 may be barely noticeable, and grade 2 affects your functioning. For example, grade 1 diarrhea might be two poops a day, and grade 1 fatigue might mean it’s resolvable with rest, but grade 2 diarrhea could be nine poops a day, and fatigue not resolved by rest is permanent fatigue. When you also add the element of time to a treatment, there is quite a big difference between grade 1 and grade 2, so we just should not combine them.”

→ Balancing Science and Medicine to Benefit Lung Cancer Patient Care

Aided by senior fellows

Camidge says he would like to see an end to “sugar coating and misleading language” in presentations about trials and more “fit for purpose” descriptions of side effects – descriptions more suitable for the circumstances of a new treatment, including the length of time a patient experiences a side effect and at what level. Those descriptions might draw more heavily on patients’ responses to detailed surveys about side effects.

“When you think about it, in lung cancer we increasingly get patients who anticipate the hope of a largely normal life and excellent control of their cancer,” he says. “They’re not just asking, ‘When can I get off the couch?’ They want to know, ‘Can I go skiing? Will I be able to dance all night?’ They want objective information about what they can expect and when it will happen.”

Camidge was aided in the survey by two participants in a two-year thoracic oncology senior fellowship program that he established at the CU Division of Medical Oncology: Alexander Watson, MD, DPhil, who is already in the program, and William Phillips, MD, currently a fellow at the University of Ottawa, Canada, who will join the program later this year. Phillips has a fondness for working with big data sets, Camidge says, and Watson was involved in methodology and writing.

“We’ve had truly outstanding individuals in the program,” he says. “They improve my quality of life immeasurably.”

Photo at top: Participants examine research posters on display at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago in June 2023. Photo by ASCO/Luke Franke.