One of the major complications of severe COVID-19 is blood clots in the lungs – a pulmonary embolism that can block lung function leading to death. In fact, these blockages are similar to those from chronic heart disease, stroke, and even traumatic injuries like a car crash or gunshot wound. In these non-COVID-19 conditions, doctors use drugs to break up and dissolve the clotted blood. Now a team led by Colorado trauma surgeon Gene Moore, MD, is testing a similar approach against the dangerous blood clots associated with COVID-19.

But a major question remains: Which coronavirus patients are developing these clots?

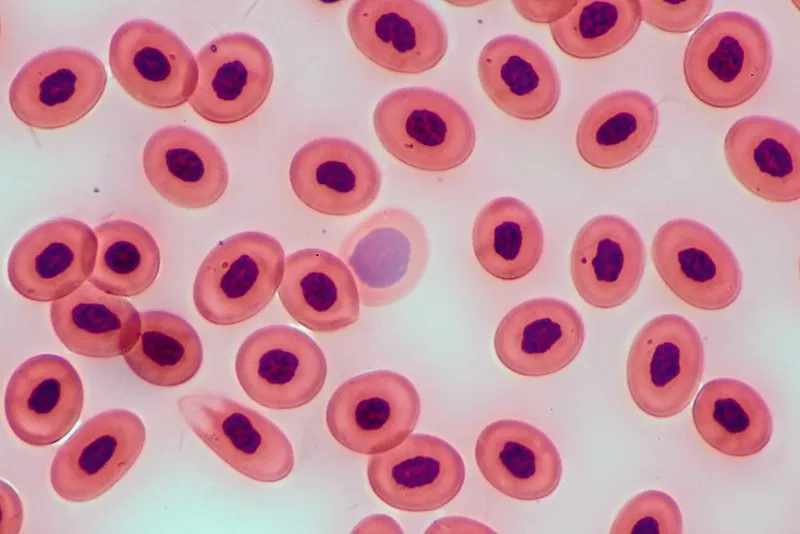

By the time a pulmonary embolism creates symptoms, a patient can be in a life-threatening emergency situation. At that point, even if a patient is ventilated, a coronavirus-associated embolism can stop oxygen from reaching the blood. With this in mind, the University of Colorado Cancer Center Mass Spectrometry Shared Resource (CU MSSR) is powering a search for signatures of metabolism and proteins that can act as early warning signs of pulmonary embolism.

“SARS-CoV-2 – the virus that causes COVID-19 – is particularly good at hijacking the host metabolism to make the infected cells manufacture the building blocks it needs to replicate faster,” says Angelo D’Alessandro, PhD, director of the CU MSSR.

Angelo D'Alessandro, PhD

The most common use of the word metabolism describes how food is converted to energy, but metabolism also includes breaking down structures into building blocks like proteins or lipids. For COVID-19 patients, these viral building blocks can be a signature of disease.

“First of all, we are using metabolites as a marker of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severity,” says D’Alessandro.

Second, with the analysis of up to 6,000 COVID-19 samples gathered with colleagues at Columbia University, D’Alessandro and his team hope to discover the metabolic “pathways” that SARS-CoV-2 uses to supply itself with the materials it needs to grow.

“Knowing the pathways rerouted by the virus could allow us to intervene in those pathways with drugs,” D’Alessandro says. Blocking these metabolic pathways could help doctors slow the proliferation of the virus in the body, and also treat complications including extreme immune responses and blood coagulation.

To predict the dysfunctional coagulation that causes embolism, the CU MSSR goes a step further. Working with the lab of Kirk Hansen, PhD, the CU MSSR is exploring protein signatures that can show when blood is developing dangerous characteristics that could lead to embolism.

At the same time the CU MSSR is helping to understand how metabolic pathways and proteins predict and drive COVID-19, D’Alessandro and his team are lending their expertise to treatment efforts. The group recently earned emergency funding through a national organization focused on trauma-associated blood coagulation to support the work of Dr. Gene Moore and the CU School of Medicine Trauma Research Center, investigating the use of the drug alterplase to treat patients with COVID-19 at risk for embolism.

For a basic researcher like D’Alessandro, working to develop COVID-19 tests and treatments offers are rare opportunity to see the immediate effects of his work.

“It feels particularly relevant due to the immediacy of the crisis,” D’Alessandro says. “Doing this work gives us the opportunity to be on the front line. It shows us right away how our work can make a difference.”