Birthdays. Anniversaries. Holidays. For each of us, each year brings special dates to celebrate.

For Emily Daniels, each year is all the more special. It’s another year of life that she once thought she might not get to live. Another year spent with her loving husband, Brian, and two young children.

“Every year, we definitely recognize it,” she says. “The way we think about life is that we just want to live each day. You never know what the next day’s going to bring.”

It’s now been just over six years since Daniels, a non-smoker who was 33 weeks pregnant with her second child, felt tightness in her chest and received an initial lung cancer diagnosis. The extent of her cancer couldn’t be determined at first because her pregnancy limited the use of X-rays.

She found her way to the University of Colorado Cancer Center. There she encountered Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, who for decades has helped lead groundbreaking research into lung cancer treatment.

After her baby was delivered, five weeks early, further tests showed that Daniels had stage IV ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. That led to a roller-coaster ride of disappointments as her cancer evolved – and then came a breakthrough with implications that could help other patients like her.

→ Video: Ross Camidge, MD, explains ALK-positive lung cancer

Photos at top: Left: Emily Daniels with her daughter, Paige. Center: Daniels with her husband, Brian, and children Brady and Paige. Right: Daniels with her son, Brady. Photos courtesy Emily Daniels.

A pretty normal life

Six years later, with her cancer in check, Daniels, 38, talks exuberantly about Camidge and the individualized care she received at the CU Cancer Center.

“The research capabilities that the university has is why I’m here,” she says. “I’ve brought other people to Dr. Camidge and they got very different courses of treatment for their cancer. It’s world class, and knowing you’re truly getting the best care is crucial to your positive mindset and how you feel.”

Says Camidge: “Because Emily is such a delightful person, and because she’s such a success, it feeds back to us and tells us, OK, this is why we’re doing this. If we can solve this and turn people’s lives around, that’s what drives us.”

Daniels has spent the last six years sharing the story of her cancer journey in interviews and helping to raise research funds so that others in her situation might live. And she’s been living life.

“I'm good,” she says over the phone while on a family vacation trip in Mexico. “I live a pretty normal life. I'm very fortunate to be living what feels pretty normal.”

As for her kids, Paige and Brady, ages 9 and 6: “For the most part, they just think that Mom’s normal,” she says. “My son does ask, ‘Mom, do you have cancer?’ But it really hasn’t been a focus in their lives.”

A molecular change

Camidge recalls an early conversation with Daniels six years ago: “I told her, ‘You have a molecular change in your cancer cells. You didn’t inherit it. It’s an acquired change that’s driving your cancer cells called an ALK rearrangement.’” ALK stands for anaplastic lymphoma kinase.

“If you have to have lung cancer, this is a better one to have, because it responds well to pills, and sometimes you can extend life for years,” Camidge says. “But if you’re a young woman who’s just had her baby, it’s a devastating diagnosis.”

Camidge put Daniels on eight pills a day of an ALK inhibitor called alectinib. A year earlier, Camidge had co-led an international trial that established alectinib as a therapy for her subtype of lung cancer.

At first, Daniels responded well. “We were saying, ‘Emily, you’re going to be the poster girl. It’s amazing,’’’ Camidge recalls.

“And then, fate decided to throw a monkey wrench. In a matter of months, her cancer stopped responding to treatment. It had evolved to become resistant to the initial ALK inhibitor.”

Everything known to science

That led to a “scramble, because the cancer was moving relatively quickly,” he says. “We tried other ALK inhibitors. We looked at everything that was known to science at that point in time in terms of known mechanisms of resistance. She didn’t have any, and her future was looking very bad.”

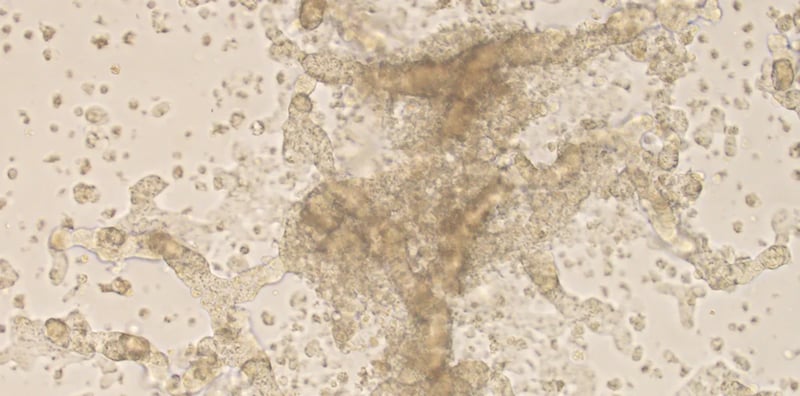

Then a breakthrough came when Camidge’s then-CU Cancer Center colleague, Robert Doebele, MD, PhD, was able to grow living cancer cells from a biopsy of Daniels’ cancer. That led to the discovery that there was a second signaling pathway, called MET, driving her cancer’s growth in addition to ALK. Although Camidge’s team had found other ways that MET could be turned on and drive treatment resistance, Camidge says Daniels is the only patient he knows of “who has her exact mechanism of MET-related resistance.”

→ Study Identifies MET Amplification as Driver for Some Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers

So Camidge added an MET inhibitor, crizotinib, to the ALK inhibitor Daniels was taking, and “she responded like a dream. She’s had pretty much a complete response on the scans for five or six years now. Could the cancer evolve again in the future? Sure. But it’s not finding a way around the treatment so far.”

A 2018 image of cancer cells grown from a biopsy of Emily Daniels' cancer by Robert Doebele's lab at the CU Cancer Center.

A 2018 image of cancer cells grown from a biopsy of Emily Daniels' cancer by Robert Doebele's lab at the CU Cancer Center.

Few easy cases

Wanting to help support cancer research, Daniels and her family have organized golf-tournament fundraisers for six years and raised more than $1 million.

And Daniels’ living cancer cell lines are helping with that research. They’re now being analyzed by CU Cancer Center member Sharon Pine, PhD, who leads its Thoracic Oncology Research Initiative (TORI), in hopes of “finding a way for testing for what Emily has in other patients without having to grow the cells each time,” Camidge says. “Emily’s case proves it’s possible that there are mechanisms or resistance in cancer cells that our current tools of analyzing a little pickled cancer specimen are missing.”

→ New TORI Director Looking Forward to Supporting Multidisciplinary Research

Asked if Daniels' case is the most complex he’s seen in his career, Camidge says: “I don’t know if it’s the most complex. The CU Cancer Center has seen cases from, at last count, 43 different states and 40 countries. They usually don’t send us the easy cases.”

He emphasizes the importance of clinical trials at the CU Cancer Center, where he says 40% of lung cancer patients are on trials, well ahead of other cancer programs in the United States. Daniels’ case, he says, is leading to more clinical trials that will help future patients.

Asked about her hopes for the future, Daniels says: “My hopes are that I continue to feel good and live a long time. At the beginning, we didn't really know what things would look like, and now I'm very hopeful that I'll have a long life, being there for my kids’ high school graduation. Being there for their college graduation may sound unrealistic, but it feels like a real possibility now.”