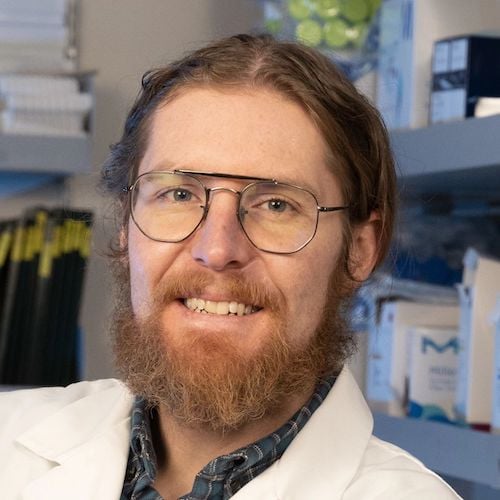

A longtime researcher of osteosarcoma in dogs, University of Colorado Cancer Center member Dan Regan, DVM, has received a grant from the National Institutes of Health to investigate a new method of stopping the bone cancer from spreading to the lungs. Known as an R37 Method to Extend Research in Time (MERIT) Award, the funding provides long-term grant support to “investigators whose research competence and productivity are distinctly superior and who are highly likely to continue to perform in an outstanding manner,” according to the NIH.

“We are targeting the microenvironment of the lung, which is the most common site of metastasis for this particular bone cancer,” says Regan, a faculty member at Colorado State University in Fort Collins and a researcher at the Flint Animal Cancer Center. “Once it spreads to the lung, we have limited therapeutic options.”

Targeting fibroblasts

Along with CU Cancer Center member Breelyn Wilky, MD, deputy associate director of clinical research for the CU Cancer Center and associate professor of medical oncology, Regan is focusing his new line of research on the biology of fibroblasts in the lung and how they promote osteosarcoma metastasis.

“A fibroblast is a connective tissue cell in our bodies that provides structural support for our organs,” Regan explains. “But they can get co-opted by cancer into an activated state that promotes growth and metastasis.”

Regan and Wilky plan to explore that transformation in their research, using a fibroblast-targeting drug, in conjunction with standard-of-care chemotherapy, in dogs with naturally occurring osteosarcoma. The first drug will target a specific signaling pathway called focal adhesion kinase, or FAK, to stop fibroblasts from encouraging metastasis.

“We found that the FAK signaling pathway is hyperactivated in tumor cells — they seem to be reliant on it for their survival and proliferation,” Regan says. “It also appears to be enriched in the tumor microenvironment, specifically within the fibroblasts, causing a feed-forward loop that calls in other tumor-promoting immune cells, like macrophages, that encourage the cancer to spread to the lungs.”

The goal, Regan says, is to target what he calls the “metastatic niche” of the lung that allows the cancer to spread there. The FAK inhibitor works with chemotherapy to kill cancer cells, but it also targets the metastatic niche to slow or stop metastasis. Though the trial will target cancer cells before they spread to the lung, he is hopeful the drug combination also will reverse lung metastasis after it occurs.

Novel target

FAK inhibitors have been used to treat other cancers, including ovarian and pancreatic cancer, but this will be the first time they have been evaluated in osteosarcoma, Regan says. While he and his team study how the drug combination works in dogs, Wilky will be doing additional research to evaluate the FAK target in human osteosarcoma patient tumor samples. Known as “comparative oncology,” the practice of studying cancer in dogs as a precursor to treating it in humans makes perfect sense from a scientific standpoint, Regan says.

“In humans, osteosarcoma is a pediatric or childhood disease, and it's relatively rare. They consider it an orphan disease — maybe 800 cases a year,” Regan says. “But in dogs, the incidence is at least 20 times higher. Part of the value of this translational research is that we can recruit patients faster and determine whether there's a therapeutic signal in our canine patients quickly, before moving it to people.”