Sapna Patel, MD, a widely renowned melanoma oncologist and clinical investigator, has joined the University of Colorado Cancer Center and the CU Department of Medicine, with a goal of helping to build a “pinnacle of skin cancer treatment” in the Rocky Mountains.

“I’m so thrilled to be here,” Patel says. "It's a place that has a clear vision to conquer cancer, where hope meets healing, and every day we have the chance to advance the care and treatment of patients with cancer.”

Patel comes to the CU Cancer Center from MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, her professional home for more than 16 years. She joins CU as a professor in the Division of Medical Oncology, where she has been appointed leader of the Cutaneous Oncology Program, and she holds the Dr. William Robinson Endowed Chair in Cancer Research.

During her fellowship at MD Anderson, Patel met Christopher Lieu, MD, now the CU Cancer Center’s associate director for clinical research and a medical oncology faculty member.

“I’ve known Dr. Patel since 2005, and I can tell you that she is not only a world-famous oncologist and melanoma researcher, but she is a kind, thoughtful, and compassionate physician as well,” Lieu says. “She has quite literally changed the field of melanoma, and she is a world-class leader. We are so fortunate to have her at CU.”

Sapna Patel, MD, with Christopher Lieu, MD, the CU Cancer Center’s associate director for clinical research, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology's 2024 annual meeting in Chicago. Photo courtesy Sapna Patel.

'Excited about the challenge'

It’s a return to Colorado for Patel, who served her internship and residency at what was then the CU Health Sciences Center in Denver in the mid-2000s before heading back to Texas, where she grew up, for her fellowship and career. “I always thought that I’d come back to Colorado at some point,” she says.

At MD Anderson, “I was fortunate to build a rare-melanoma program that started as a philanthropy-funded effort and expanded to a grant-funded multidisciplinary team leading clinical trials and translational research. We became a high-volume referral center for patients with melanoma of the eye, a cancer that afflicts merely one in 6 million persons.” Patel says. “I got to a point where I thought it was time to hand it off to someone else and see if I could build this again somewhere else, maybe even better resourced. I’m really excited about the challenge of building it here and expanding the high caliber CU melanoma program.”

Besides, she says, the Rockies should be home to a top-notch skin cancer program, “given that we’re at altitude and with all the sunny days.”

Patel also is chair of the Melanoma Committee of the SWOG Cancer Research Network (formerly the Southwest Oncology Group), a global cancer research community funded by the National Cancer Institute.

In that role, Patel led a pivotal study known as SWOG S1801 that established the superiority of perioperative immunotherapy compared to the standard of care approach, which is immunotherapy given entirely in the post-operative setting. This randomized phase 2 trial was presented by Patel at the 2022 ESMO Congress in Paris in a Presidential Symposium and subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine. This was a practice-changing trial for skin melanoma, and Patel hopes to expand these findings to rare melanomas and other non-melanoma skin cancers.

Sapna Patel, MD (second from right) at dinner with melanoma oncologists from around the world during a SWOG Cancer Research Network meeting in October 2023. Photo courtesy Sapna Patel.

‘Such a special place’

Patel is the daughter of immigrants who “came here with a lot of opportunity in mind for their kids.” After her undergraduate years at the University of Texas in Austin, Patel spent a year in AmeriCorps, the domestic version of the Peace Corps.

“The east side of Austin has a socioeconomic divide from the west side of town with a large working migrant population and several community health centers,” she says. “I worked at a number of those clinics, helping to set up a pediatric literacy program called Reach Out and Read, which had been started by a pediatrician in Boston and involved demonstrating reading to children in waiting rooms during well-child visits, providing them with free books, and encouraging the pediatricians to prescribe nightly reading to parents on actual prescription pads.”

She adds: “That experience solidified my desire to go into medicine. It felt like something I could do, and no one was telling me no.”

It was in Patel’s third year of medical school at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston “that I realized oncology was such a special place. I did a rotation with Dr. Dennie Jones, a lung cancer doctor. This was before many of the great strides in oncology, and often he was telling patients that there were no more treatment options left, and yet those visits would end with patients standing up and hugging him and a family member saying, ‘Thank you.’

“I told him I didn’t understand what was happening – he was giving these patients bad news, and I was seeing them react with gratitude rather than anger or sadness. And he replied by explaining that cancer patients have the capacity to process their journey with grace and strength. I’ve found that to be true to this day.”

A safety net

Patel says she was drawn to melanoma for several reasons. “I knew of people who had melanoma that went to the brain. I remember thinking, how does it go from the skin to the brain? I was struck by the fact that it could be fatal like that. It turns out, melanoma is the third most common cancer that spreads to the brain.

“Also, I like skin stuff. I like makeup, beauty and skin care products, the natural biology of skin, and also its pathophysiology, what can go wrong with skin.”

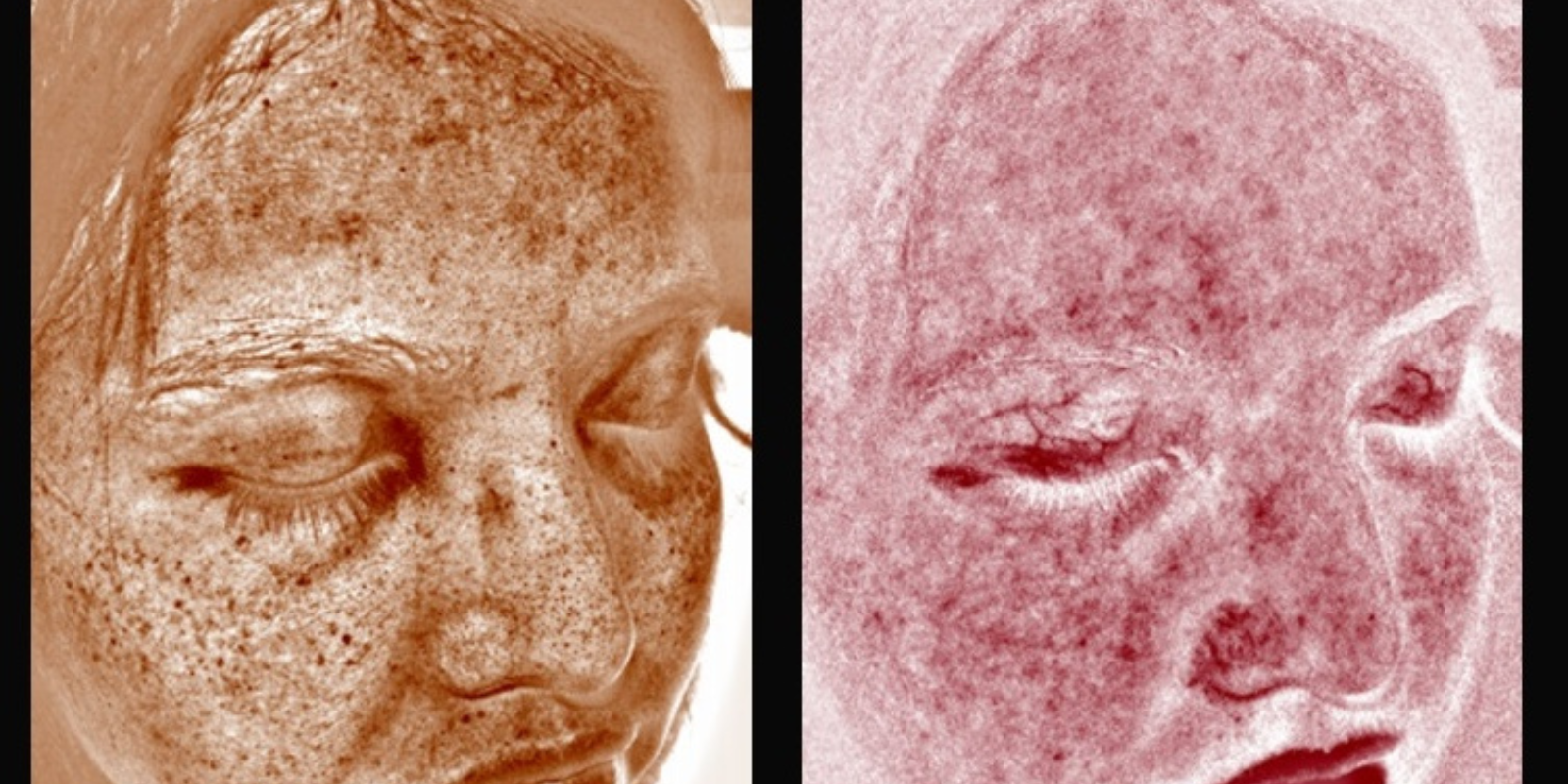

During her fellowship, Patel rotated with an oncologist who specialized in melanoma of the eye – including uveal melanoma, which affects the choroid layer, the ciliary body, or the iris of the eye. It’s a relatively rare but dangerous disease that, if left untreated, can spread to the liver and other organs.

At the time, Patel says, treatments were ineffective and there were no clinical trials. She saw an opportunity and asked to see uveal melanoma patients earlier in their journey, before their cancer had metastasized, in hopes of learning more about how to treat them effectively. “It was a massive patient stream that the department hadn’t seen before, because usually they were waiting until they became metastatic. And I really fell in love with being a safety net for these patients, getting to know them as unique individuals over the years before their cancer took a wrong turn.”

Filling the gaps

That experience led Patel to rare melanomas – also known as non-sun-related melanomas – being a focus of her research work. “In melanoma, we were the first to get a checkpoint inhibitor approved, we were the first to get a tumor-infiltrating T cell therapy for solid tumors approved, and a first-in-class bispecific molecule for uveal melanoma. I like filling the gaps in treatment of these rare melanomas.”

Given her interest in melanomas of the eyes, Patel is glad to be working in close proximity to the UCHealth Sue Anschutz-Rodgers Eye Center on the CU Anschutz campus. In fact, she has a joint appointment in ophthalmology.

“I hope to be seeing patients in the ophthalmology clinic alongside Scott Oliver, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology and director of the Eye Cancer Program. When you go to the eye doctor, they dilate you, and then they put you back in the waiting room and you’re spending time waiting, and that’s valuable time where I could be seeing the patient while their eye is dilated. Here, the cancer pavilion and the eye clinic are right next to each other.”

In addition to continuing her hunt for new melanoma therapies, Patel hopes to “learn more about what drives these cancers to turn on. It’s not clear in the rare melanomas that it’s ultraviolet driven. If we know what’s turning them on, sometimes you can figure out how to turn them off.”

.png)